Sierra Leone

Benji Kamara isn’t a rich man. It’s something he’s had to repeat many times over the past few months. While planning his first trip in more than two years to his home in Sierra Leone, the Smithers resident struggled to think of a gift he could take home to his people.

The answer came via friends, and connections with the Smithers-based NGO One Sky: they would hold a fundraiser, and find some way to help the people in the warn-torn West African country. Then Kamara, who has a background in community development and youth work, came up with the answer: they would raise money to send Sierra Leonean children to school.

“With education, there is a long way to go. One major thing in my country is my people are easily misled,” he says, describing a nation where an educated minority has abused the resources and marginalized the people. “Why they are easily misled is because people don’t have an education. People don’t know their human rights.”

“These guys who don’t go to school, they can’t argue. The only thing they can say is, ‘you are treating me this way because I am uneducated.’ If there is no education, how are you going to be able to take care of your country? No way.”

Sipping coffee in his sunny Smithers living room on a quiet Sunday morning, Kamara is a long way geographically from the country where he grew up. He has a relaxed smile and uses his country’s colloquial name—Salone—with a gentle drawl that reveals a deep affection for his homeland and the people he left behind.

Although Kamara’s peaceful demeanor may not show it, his mind is never far from his days of survival during Sierra Leone’s 11-year civil war. He’s keenly aware of the simple things we take for granted—like sitting here on the couch, for instance. In Sierra Leone, we would be holding our conversation lying on the floor where, in the case of an unexpected explosion, we would be less likely to get hit by flying debris.

Also, there is the food—the limitless supply of sustenance always available to us here in Canada. Rarely does Kamara sit down to eat without thinking of his friends back home who still struggle to make ends meet.

And then there is education.

When war first broke out in the rural areas of Sierra Leone in 1989, Kamara had just finished his elementary school training. As the rebels from the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) moved into Freetown, his father’s business began to suffer and it was up to Kamara to fend for himself. He dropped out of school and began working odd jobs. He also made soap and jewelry to sell to street vendors, and played soccer, to earn money.

Kamara was also involved with a local organization that was working to empower youth. The experience fuelled his interest in community development and connected him to One Sky, where he met his partner, Kristin Patten, and eventually moved to Smithers.

“That’s when I started having a sense of organizing. That’s when I first joined an organization,” he says, describing a need to rise above the struggle and look after his community. “That’s where we started having a sense of ‘what are we doing?’ instead of ‘the government isn’t doing this or doing that.’ What are we doing?”

But while people like Kamara learned to survive, many dropped out of school and sat idle, waiting for the political situation to improve. These are the ones who were vulnerable to rebel influence, he says, and most likely to be recruited by the RUF.

“I have a strong connection with youths,” Kamara says. “A strong, strong connection. I don’t want them to be carried away, because they don’t go to school, by politics and some of the craziness out there.”

That’s why, when the idea presented itself last fall to fund children’s schooling back in Sierra Leone, it seemed like the logical next step for Kamara. Maybe, he thought, they could raise as much as $2,000. “When we started, I was saying if we can help five kids, that would be great,” he remembers. “Then look how it goes. It was just going, going and going and look how many kids benefited.”

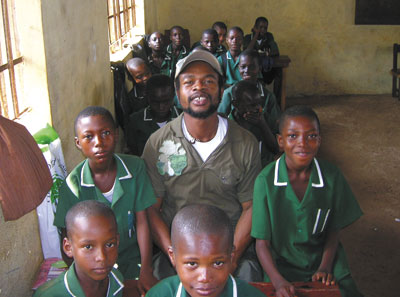

In the end, Kamara’s team raised more than $7,300 and enrolled 450 children in school by purchasing uniforms and books for elementary school children and paying registration fees for 90 secondary school kids.

In particular his efforts focused on girls, who often receive less priority within the families’ budget for education. Schooling offers the girls a chance to learn tailoring or business skills, which also help them to run the home, Kamara says. As well, it keeps them occupied and less likely to get pregnant—something that would force them to give up any chance of an independent future.

In return, many of the girls assisted by the program pledged to Kamara that they would work hard to get good grades. “I really felt those words,” he says with a smile. While most Canadian children bemoan the early mornings and long days in class, children in Sierra Leone would come to Kamara’s door hoping for the greatest gift: the chance to attend school, play sports and socialize with the other kids.

But beyond educating African children, the program has also been a learning experience for school kids here in Smithers. Working with teachers at St. Joseph’s, Muheim Memorial and Walnut Park elementary schools, Kamara enlisted the help of local children who painted flowerpots that were sold to raise money. He recently returned to their classrooms with photos from his time in Sierra Leone.

“It’s really neat to see the pictures of the kids in Sierra Leone with Benji. He can say, ‘this kid wasn’t managing to go to school and we could pay for his uniform and sign him up right there,’” says Anne-Marie Findlay, a Grade 4-5 French-immersion teacher at Muheim Memorial Elementary. Three classes at Muheim were involved with the project, and the school also donated $600 from a Ten Thousand Villages craft fair it hosted.

“A lot of them are quite attached to the whole project,” she adds.

But the program’s initial success is a double-edged sword, bringing with it certain expectations and pressures. “I’m not a rich man,” Kamara would continually repeat, attempting to explain the concept of philanthropy to people with barely enough to feed their own families. While 450 children are currently in school, there are no guarantees for their future education—and still thousands more who could benefit from the program.

As local interest in his project grows, Kamara says he hopes to see others come on board, bringing with them their own ideas of how to bring schooling to Sierra Leonean children.

“A lot of people were like, ‘Benji, this is what we’re supposed to be doing,’” he says.

“This is what I’m meant to do. I have a feeling like I’m starting on my path in life. It’s giving me a lot of strength spiritually, mentally and physically. It’s hard for me, even when I’m living in Canada. I was a poor guy in Sierra Leone, but there is always food here. Sometimes I sit down and I just can’t eat.”

Kamara’s dreams of educating the people of Sierra Leone have only just begun. He hopes to help the current project evolve into a permanent trades-school back in Freetown, offering courses like tailoring, baking and other practical skills. His vision is for a program that sustains itself through a retail component, without external funding.

“I don’t know when this is going to happen, but this is my passion,” he says, with the conviction of a man who has found his calling in life. And though it may not be reflected in the car he drives or the balance in his bank account, it’s apparent that Benji Kamara is, indeed, a very rich man.