Cataline

On the edge of a hill in Gitanmaax Cemetery there is a small rock cairn that overlooks the confluence of the Skeena and Bulkley rivers and has for a backdrop the black rock face of the Roche DeBoule range. The stone marker reads, “Jean Jacques Caux – Cataline, the packer—1830-1922.”

Jean Jacques Caux was nicknamed Cataline on the misconception he was from Catalonia, a once-independent kingdom bordering on his birthplace of Bearn in France. He spoke a rapid mixture of French, English, Spanish, and Chinook jargon, the First Nation-European trade language that was common in the Pacific Northwest at the time.

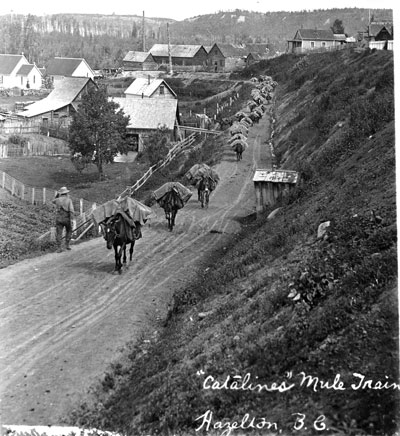

Cataline left his home country and eventually made his way to British Columbia with other gold seekers. He drove large teams of mules and horses out of Yale, Ashcroft, Quesnel and Barkerville during the gold rushes of 1858, 1863 and 1898. Cataline’s pack trains went where wagons could not, carrying goods and equipment through the wilderness and over difficult terrain.

As the gold rushes led to wider roads in the Cariboo, Cataline’s pack trains were no longer needed and he moved north and west into the Bulkley Valley and the Hazeltons.

He supplied the early settlers, prospectors and telegraph linesmen with much-needed supplies and had good relations with the First Nation groups in whose territories he travelled. Cataline’s pack trains were significant in size, employing five to six men with 30 to 60 mules carrying 250 to 300 pounds each. Their movements made the early newspapers throughout the province as citizens and storekeepers anticipated their arrival.

Commanding presence

Sperry ‘Dutch’ Cline was the Provincial Constable in Hazelton in the early 1900s. In his memoirs he refers to Cataline as “a striking figure with a Buffalo Bill head of hair and a Napoleon III imperial beard—broad-shouldered, barrel-chested and tapered from the waist to the narrow hips and thin shanks of men who spend a lifetime on horseback. His already commanding presence was further enhanced by his apparel, which seldom varied: a broad-brimmed sombrero, a silk handkerchief around his neck, a frock coat, heavy woolen trousers and a rather dainty pair of riding boots.”

Wes Jasper was part of an experimental cattle drive in 1910 that brought cattle from the Chilcotin to Hazelton. Jasper encountered Cataline in Quesnel with an incredibly large 60-horse and 60-mule pack train. He kindly offered Jasper advice on places to overnight the cattle where there would be enough feed for the animals.

Cataline was reportedly helpful to the local First Nations, handing out provisions when he felt it was needed and not asking for repayment. Unlike some of the other operators, Cataline never had animals go missing at night. He soon became a renowned pack-train operator, with a firm hand and a very strong team.

Cataline met an aboriginal woman named Mary in Wrangell, Alaska early in his life; they married in 1876. Together they had a daughter named Clemence. Cataline later married Amelia York of Spuzzum and had two or three children with her. He may not have seen much of his children, but records show he kept in contact. Amelia regularly received gold eagle coins from him.

With an amazing memory, Cataline always knew where supplies were going, how much was owed to him for his goods, and how much he owed his own employees. Keeping no written ledgers, he was able to retain and recite everything from memory. When settling up with an employee Cataline once said, “Six dollars cash to Soda Creek; two dollars 100 Mile House; three dollars Clinton; five dollars Lac La Hache; two dollars Bonaparte Reserve; three dollars Ashcroft; fifty cents 150 Mile House for tobacco; two dollars Hazelton for whiskey; five dollars Hazelton pay fine.” After doing the calculations in his head he had a store agent write a cheque and let the packer go.

He managed very large quantities of gear and reportedly every item ordered arrived at its destination, except one incident when one of his packers mistakenly threw out two pounds of Limburger cheese, thinking the package contained something rotten. Cataline learned of the mistake and promptly ordered a replacement cheese.

At one point Cataline lost some of his pack animals to disease and went to a bank for a loan to purchase replacements. Upon hearing how many horses and mules he owned, the bank granted him the loan. At the end of the season, when Cataline returned to repay the loan, the manager observed that he had a significant amount of money on him and suggested he put it in the bank. But when Cataline learned the bank owned no mules or horses, he decided the money was best kept with him and his team.

Peacekeeping weapons

He was always willing to travel to new mineral claims and remote settlements. Never refusing the needs of a customer, he once transported a steam boiler cut into pieces and strapped on the mules’ backs and, amazingly, a piano balanced on a mule with props on each side. The mules were well trained and reportedly went to stand beside their packs when a bell was rung. His employees, on the other hand, may have not been so well behaved: Cataline is said to have carried a mule shoe in his jacket to break up disputes among his crew.

The horseshoe was not his only weapon. He kept a long Mexican knife in one of his tall boots and once stopped a riot from erupting between the Judge Begbie and some angry miners. The miners were about to rebel against Judge Begbie when Cataline’s pack train arrived. When asked which side he was on, Cataline drew his long knife out of his tall boot and announced, “I stands by judge!” The angry miners sized up Cataline and his husky packers and decided to let the disagreement lie. The judge did not forget this favour.

Years later, Cataline’s claim to his land was being challenged because he was not a Canadian citizen. Judge Begbie went out and declared Cataline a Canadian citizen in an impromptu court session on the dusty Cariboo road. When the land issue was called to Judge Begbie’s court he declared, “Why, I myself declared Cataline a Canadian citizen. Next case!”

The end of the trail

Cataline retired in 1913, at age 83. He sold his pack train operation to George Beirnes of the Kispiox Valley and settled down in a small cabin Beirnes gave him on Mission Point, across the Bulkley River from Hazelton.

Cataline was a tough man who spent most of his life outside. He encountered many days of inclement weather while riding over difficult terrain, cooking over a fire and sleeping on a canvas pack-cover under the stars.

Even in his late retirement he showed he was made of tough stuff. He reportedly never wore socks, even in the coldest of winters. Cline, Cataline’s friend from Hazelton, recalls one especially cold and icy January when Cataline came into the Hudson Bay Store and asked for one pair of thick wool socks. Heads turned and the locals wondered if old Cataline was finally feeling the cold. But before leaving the store he pulled his new socks over his leather boots—for sure footing on the slippery ice.

When his health began to fail he refused to go to the hospital. His friends once carried him out of his house and loaded him on a wagon destined for the hospital, only to see him revive in the fresh air, roll out of the wagon and return to his cabin.

In the autumn of 1922, at the age of 92, Cataline died and was buried in the Gitanmaax Cemetery in Hazelton. The memorial cairn there now was established by the citizens of Hazelton after they could not locate his grave. His descendants will return to the cemetery this summer to mount a brass plaque on the cairn for Cataline, the indomitable packer.

Cataline reference file at my own home/Cobweb Research Business (www.cobwebresearch.com), containing personal correspondence with Cataline’s descendants and newspaper clippings from the early area newspapers – Interior News and Omenica Herald (searchable online through the Terrace Public Library website).

Other sources: – ‘Cataline’ by Sperry Cline, Burnaby B.C. March 1959 – ‘Cataline’ by Louis LeBourdais, in The Province, Vancouver, September 27 1925 – ‘Jean Caux’, by A.C. Milliken, in Frontier Days in B.C., Sunfire Publications, 1993 – ‘Memories of a Famous Packer’by Wiggs O?Neill, in Kitimat Northern Sentinel September 27, 1962 – ‘Early Days in the Nechako Valley’, by George Ogsten, Pioneer Days In British Columbia, Volume 4, 1979 – ‘Martin: The Story of a Young Fur Trader’, by Imbert Orchard, Sound Heritage Series no. 30, Victoria B.C., Provincial Archives, 1981 – ‘Before Roads and Rails: Pack Trails and Packing In the Upper Skeena’, by Sandra McHarg and Maureen Cassidy, 1980