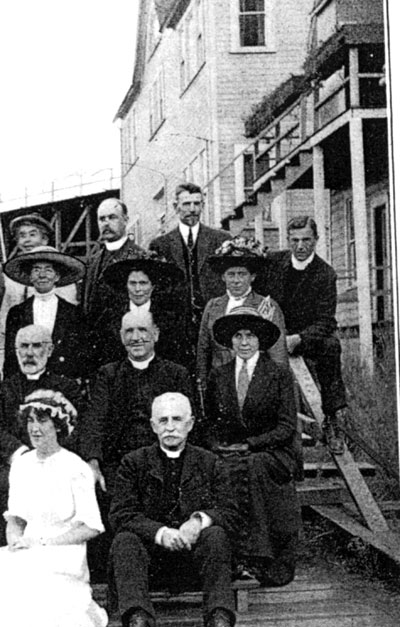

Rev. Fred Stephenson

When the Bulkley Valley’s Mel Coulson marvels at the early pioneers’ strength of conviction, he is thinking of one man in particular: the Reverend Fred Stephenson. “He seemed to be inured to cold, capable of immense physical exertion, and able to exist on the most meagre food rations.”

Coulson should know; he spent many months researching the life of Reverend Stephenson. What began as a small project, researching the history of the Anglican Church in northern BC for his fellow Anglican Church parishioners, resulted in a vast amount of material and lots of anecdotes about Stephenson’s life.

Fred L. Stephenson came to Victoria from England in 1884. He was ordained into the Anglican Church in 1889 and the same year married Emily Fisher. The newlyweds took a small three-masted steamer up the BC coast and lived and worked among the Coast Tsimshian in Kitkatla. Emily gave birth to their first daughter in 1891 but they lost her to whooping cough that spread through the village. Four more children were born to them in Kitkatla, followed later by two more as the family moved around northern BC.

In 1898, Stephenson was dispatched to Bennett Lake to minister to the thousands of gold seekers pouring over the Chilkoot Pass to seek their fortunes in the Klondike goldfields.

In 1899 Stephenson walked into the pioneer gold-mining town of Atlin. He preached throughout the town wherever he could. It was in Atlin that he earned his nickname “the fighting parson.” Allison Mitcham, in her book The Last Utopia: Atlin, writes that the Reverend was being harassed by a rough miner who told Stephenson, and the crowd gathered around them, that if Stephenson wasn’t a man of the cloth he would whip him. To which Reverend Stephenson threw his coat on the ground and said, “There lies the cloth, here stands the man. Come to him.” Coulson continues the story: “Shocked out of his bullying stance and regaining some measure of sobriety, the miner backed down and offered Stephenson his hand.” Such a fighting stance gained respect and reputation in the rough-and-tumble northern community.

The Walking Parson

After several years in Atlin, and walking many hundreds of miles to preach to surrounding camps and communities, the Reverend was offered a three-month holiday by his Bishop. He could go south for a break, or he could attempt a hike, in winter, through mountain ranges known to be inhospitable even in the best summer months, along the telegraph line and onwards to Kuldo, Kispiox, Hazelton and eventually to Aldermere in the Bulkley Valley. Stephenson wrote, “my friends tried to dissuade me from it. But as I had suggested the trip to my bishop and he had taken me up and called my bluff I either had to make good or stand down.” He decided he had to take the “holiday” and do the trek from Atlin to Aldermere.

As winter arrived in 1905, the Reverend began training to get himself fit for the trip. “Every day I did not less than 10 miles tramping or snowshoeing over the worst country I could pick, deliberately choosing places where difficulties were bound to be met.” The men living in isolated cabins along the telegraph line heard of his plan to hike the route and sent him encouragement over the wire; they were lonely for company and looked forward to a guest.

January of 1906 arrived, and with it heavy snowfalls. Reverend Stephenson wrote that on March 3, 1906 he “...hooked up the dogs, waved goodbye to those who stood on the wharf of [Atlin Lake] to see me start and began the first lap of my long-talked-of trip.” A three-dog team was used to haul a sled and pack the gear. Stephenson valued his dogs and knew that their strength had to be conserved or they would never endure the months of daily work ahead, so he packed the snow ahead of them. “I broke the trail for half a mile stretch and then returned over my tracks to pound the snow more solidly before I put the dogs to work to haul the loaded sleigh that far,” he wrote. He knew that “unless the trail was broken for them we would make less distance in the day’s run and the dogs would be more fatigued.”

The Reverend slept in linesmen’s cabins or the ‘refuge cabins’ between them, or he covered himself with canvas and bedded down with his dogs. He crossed treacherous ice, broke his snowshoes, built temporary bridges and used ropes to lower dogs, gear and himself down steep slopes. After leaving the telegraph trail and breaking out on his own path, he ran out of food but was lucky to come upon a trapper who welcomed him to a feast of lynx stew.

Forced to abandon his sled at the Nass Summit, the dogs carried on with 40-pound packs. In fitting biblical language Stephenson called the entrance to the pass “the Jaws of Death,” the other end “the Gates of Hell.” He crossed the Nass River and walked to Kuldo and Kispiox. After 46 days of steady slogging, he met his brother on the trail outside Hazelton. So travel-worn and emaciated was the Reverend that his own brother didn’t recognize him.

In May 1906 Stephenson pitched a tent at Tyhee Lake. The Walking Parson meant to return to Atlin but was asked by the Bishop to stay on in the Bulkley Valley. He made his home in Aldermere (near present-day Telkwa), and built a mission room to live in and work from. His wife and children came from Metchosin to join him at Aldermere, and another child was born.

Sky Pilot Stephenson

Reverend Stephenson’s work was not confined to the Bulkley Valley. Settlers had begun to move to Pleasant Valley (now Houston), North and South Bulkley, Burns Lake, François Lake and Ootsa Lake. Every winter, Stephenson strapped a 75-pound pack on his back and set off on a journey of 200 to 300 miles. He writes, “Many a time I thought the only difference between me and a mule was the length of my ears.” He preached in whatever covered space was available; people sat on overturned apple crates and barrels. If a stranger happened by and glanced in through a window they wouldn’t be able to tell the reverend from the common folk. The settler’s referred to him as a sky pilot, meaning he had a direct line to the heavens.

Reverend Stephenson stayed in the Bulkley Valley until 1913 when he followed his wife and children to Victoria. He was appointed Rector to Ladysmith until 1914 when he, along with his two oldest sons, enlisted in the Canadian Forces. He served as chaplain with the 49th (Edmonton) Battalion. He was wounded and gassed, and convalesced at Shaugnessey Miltary Hospital. He returned to minister at Cowichan and Victoria before retiring in 1927. He died in 1941 at age 77.

“The people that lived before us seem a different breed altogether,” concludes Coulson. “They were tough and resourceful; somehow we have gotten soft since that time.” Fred Stephenson certainly epitomizes Coulson’s idea of the pioneering spirit.