A hard day’s night

At the head of the Douglas Channel, nestled in a valley surrounded by the snow-capped Coast Mountains, is the well-kept little town of Kitimat. The ‘aluminum city’ is a multicultural community where Portuguese, Italian, German, Greek, English, Punjabi and Haisla languages can all be overheard at the City Centre Mall.

The people here also speak another language: the language of shift work. They can readily translate “she’s on her two-four”—she’s off for twenty four hours between two twelve-hour day shifts and two twelve-hour night shifts. They know “he’s on graveyard” means he’s working from 6 pm to 6 am.

Kitimat is a shift-working town, where foil-covered windows shut the daylight out of a shift worker’s bedroom; where most children have had the strange experience of eating dinner and going to bed while Dad has breakfast and heads off to work; where new drivers practice their merging and lane-changing skills during shift-change traffic—the only time of day when there is any substantial traffic here.

This small town of nearly 9,000 has the usual shift-working population of emergency personnel, health care workers, gas station attendants and drive-thru coffee shop staff. But the majority of the town’s shift workers are employed across the Kitimat River Bridge in the rambling industrial side of town.

Over the river

Kitimat is a planned community that came into existence in the 1950s, built to house the initial construction crews, and the company employees that followed, of the new aluminum smelter built by Alcan (formerly the Aluminum Company of Canada—now Rio Tinto Alcan). Landscape architect Clarence Stein designed the town-site, featuring large greenbelts between curved streets, pedestrian-friendly sidewalks linking neighborhoods, and industries that are visually and physically distant from residences and retail services. The major industries of Kitimat are situated well below the town, across the Kitimat River, near the salt water of the Douglas Channel.

Hundreds of cars rattle across the blue bridge over the Kitimat River every day, commuting with the shift changes to and from the industries along Haisla Boulevard on the other side.

The first industry you’ll see there is West Fraser’s Eurocan Pulp and Paper Company. A conglomeration of grey buildings and large piles of wood chips is visible behind the employee parking lot. This industry, the local “cloud factory”—with cumulus billows of steam rising from the stacks—is a world-scale producer of linerboard and kraft paper.

Eurocan employs 440 people and has three shift patterns that make sense to the average person: a straight day shift, a ‘four-on, four-off’ shift (two days and two nights, followed by four days off); and when the large, deep-sea vessels come into the docks, there are ship-loaders’ shifts: eight-hour day, afternoon, and night shifts. This all seems like a reasonable amount of shift work for round-the-clock industrial productivity.

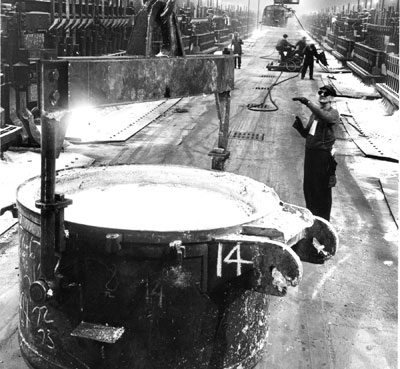

Further down winding Haisla Boulevard is Rio Tinto Alcan, a sprawling industrial site literally humming with electricity. The smelter operation is spread out along a mile of private road. Security gates and fences surround the operation—the long potlines, the tall paste plant, the calciner, the seaside docks, all linked by conveyor systems and roadways.

An industrial marvel in size and organization, the Kitimat smelter employs nearly 1,500 workers from Kitimat and the neighboring community of Terrace, and can produce up to 272,000 tonnes of aluminum annually.

Shift diversity

The employees work one of approximately seventeen different shift patterns. These vary from the typical nine-to-five day shift to the really unusual ‘Kemano Shift,’ where workers are ferried or flown to work at the power station in isolated Kemano, working seven-and-a-half days straight, then returning home for seven-and-a-half days off. Between these two extremes are the majority of employees, working all the rotation-shift combinations you can imagine.

Shift-rotation schedules eventually require a person to work at night and sleep during the day. Our bodies have their own circadian rhythms—internal clocks that usually operate on an active-day and restful-night rhythm. Working at night and sleeping during the day is contrary to our body’s biological clock. Studies have shown that shift workers sleep two to five hours less per day than ‘day workers.’ The cumulative sleep disturbance makes it harder to recover from physical and mental demands, and affects concentration, memory, reaction time, and motivation. Lack of regular, substantial sleep can result in increased heart disease, stroke, gastric illnesses, depression and infertility, compared to people who do not do shift work.

But there are ways to minimize the negative effects of shift work. Medical experts suggest that establishing a sleeping routine at home is key to training the body to rest and recover. Diet also influences shift-worker health: avoid salty, high-fat vending-machine snacks and ignore the tempting coffee stations. Bring a bag lunch and eat small snacks throughout your shift. Steer clear of tomato-based foods during night shift and you may be able to quit those antacids. WorkSafe BC suggests that employers schedule strenuous activity for the beginning of the shift, accommodate short, frequent breaks, and incorporate shift-work issues into safety meetings.

And the benefits

Shift workers in Kitimat say that social routines and family life are a challenge. Everything is designed for the dayshift majority, from banking and sports to concerts and parent-teacher nights. But despite the obstacles to working while their families sleep, and trying to sleep through snow blowers and lawn mowers, some say there are advantages to shift work.

Most significantly, shift workers are well compensated financially. Earning $80,000-$100,000 annually, Alcan’s shift workers are eligible for overtime, shift premiums, and other benefits. Some have completed correspondence courses during slow times in their shifts. Combining paid days off with a holiday extends home or vacation time. Workers at both Alcan and Eurocan maintain that their shift mates become their close friends, describing their co-workers as a kind of patch-work family.

The community of Kitimat has coped with its shift-working population. Some soccer teams have two coaches on opposite shift schedules so the team is always being cheered on by one of them. It isn’t unusual for curling teams to have co-operative pairs on their teams. Families have adapted to counting out bizarre shift schedules on the family calendar to plan events.

The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety estimates 25 percent of Canadians work some type of rotational shift-work. The retirees, current shift workers, and members of Kitimat’s two Union Halls offer this advice for those in BC who wake up in the afternoon and work all night at the gas station or the hospital; for those who still manage to drive their kids to early morning swim class after working all night at the mill: Try to form a sleeping routine. Try to have at least one meal together with your family every day. Avoid sleeping pills. Use foam earplugs. And, the shift workers at Alcan say—with a twinkle in their tired eyes—“Nothing blocks the daylight from the bedroom window like aluminum foil.” means to promote income diversity, build community, and foster economic sustainability in the North.