Horetsky’s historic hike across Northern BC

Last November, a couple of weeks before Shames Mountain opened for the season, I found myself standing on the side of a run, watching with

Despite dire warnings of thick brush, massive swamps and impassable mountain ranges, explorer Charles Horetzky is determined to walk from northern Alberta to Fort Simpson (Lax Kw’alaams) on BC’s Pacific coast. He packs nine horses with 230 pounds of flour, 12 pounds of tea, 24 pounds of sugar, 150 pounds of pemmican and other supplies. On Sept 2, 1872, along with botanist Dr. John Macoun and two guides, he leaves Fort Edmonton.

Charles Horetzky, 34 years old, arrives in Fort Edmonton as the official photographer for Sir Sanford Fleming’s cross-country survey crew from Upper Fort Garry (now Winnipeg, Manitoba). Despite having taken stunning photographs on that journey, Horetzky is cut loose at Edmonton: Fleming sends him on a mission to walk through the mountains, over difficult terrain, to the coast of northern British Columbia—in the winter. He is told to verify the elevation of the Peace River Pass, to record descriptions of north central BC, and to see if the route would be a possibility for the proposed transcontinental railway.

Others might have balked at the great distance, the approaching winter, the unknown…but Horetzky takes the challenge and travels from Fort Edmonton to Fort Simpson in the winter of 1872-73. He photographs his journey and keeps a journal, leaving behind a dramatic account of his travels.

First leg

From Fort Edmonton, Horetzky and his group travel through northern Alberta towards the BC border, encountering a grizzly bear, accidentally starting a small wildfire, and eventually abandoning their cart and most of the horses due to the difficult terrain. In early October they arrive in Dunvegan, continue to Fort St. John, and on to the Rocky Mountain Portage. It is in the Rockies that Horetzky learns of another pass, the Pine Pass; the First Nations tell him this route would be the best choice for a railway or a road through the mountains.

Horetzky and companions canoe the Parsnip, Peace and McLeod Rivers to McLeod Lake, arriving at Fort McLeod on Nov 5. Horetzky uses dogs to carry his gear eighteen miles in eight days to Fort St James on Stewart Lake. Here Dr. Macoun heads to Victoria with his rattling tin plant-presses full of samples. On Dec 2, Horetzky restocks flour, tea, sugar and “…the dietary institution of British Columbia–bacon and beans.” He and his three First Nation guides “very reluctantly resumed [their] weary tramp, which was to cease at whatever point on the coast [he] might be lucky enough to find the Hudson Bay Company steamship the Otter.”

Horetzky describes his path to Babine Lake as difficult, “during which slips and falls were the rule and upright walking was the exception.” He describes his camps as “wretched,” with far too many “angular beds.” The walking is difficult as there is too little snow for snowshoes, “and deep drifts we came upon rendered it very heavy work.”

They reach the shores of Babine Lake on Dec 10 to find the lake still open. On the edge of the ice Horetzky finds a “wretched apology” for a canoe. They “…found the canoe so unsteady that great care had to be taken to prevent our upsetting.” The canoe leaks like a basket but despite “excessively depressing spirits, sudden gusts of winds and large swells” they make progress down the lake.

At Fort Babine, two new First Nation guides are hired, one of whom is recommended as a master of the French language. “I found out afterwards,” writes Horetzky, “ his sole vocabulary consisted of the adverbs oui and non which he used at every possible occasion, regardless of consequence.” Despite the communication problems, he finds them “active and willing.” They leave Fort Babine Dec 15, heading through the Suskwa Pass for Hazelton. Horetzky notes that “the path was rough with numerous deep ravines, necessitating laborious ascents and descents; great care was taken over their steep and icy sides.”

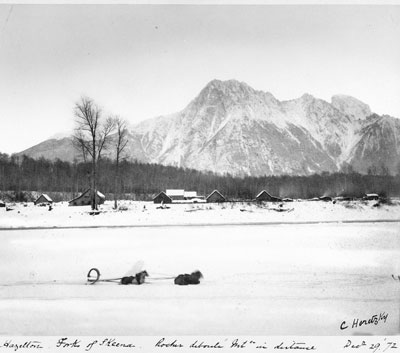

Christmas in Hazelton

Just before midnight on Dec 18 they arrive in Hazelton and are welcomed into Tom Hankin’s Store and Hotel for a “homeopathic dose of hot scotch.” Horetzky decides to stay in Hazelton for Christmas celebrations, which consist of several days of consecutive festivities: a constant din of music, singing, dancing and bar fights with fireworks, muskets and revolvers firing. He stays for two weeks, exploring the area, taking photographs and describing the people and places of early Hazelton.

Restocking with flour, bacon, beans, tea and dried salmon, Horetzky leaves Hazelton Jan 4 with “four coast Indians who engaged with [him] at the very moderate rate of 75 cents a day.” The guides speak Chinook, and not one word of English.

His first night away from the comforts of Hazelton is off to a poor start as the group sleeps “in a spot that had foreboding aspect and did not allow sufficient level space for a dog to coil up in.”

They pass the village of Kitseguecla, which he records as being deserted, to attend a feast. Further down the trail they meet over one hundred Kitseguecla Indians “returning from a great feast in Kitwancole…all men, women and children laden with large cedar boxes filled with rendered grease of the candle fish caught in the Nass waters.”

The days are very short and Horetzky’s progress is slow; “The snow is three and a half feet deep and extremely wet and soft…we pushed on, the trail becoming very much worse, the barometer falling steadily, and a constant drizzle of fine hard snow totally obscuring the mountains.” On Jan 7 they reach “Kitwancole, a village of about twenty large houses. For the last ten days this village had been the place of barter between the Nass Indians and those of the Interior.”

Along the trail the group encounters “Muskaboo” who guides them to the Chean-hown (Cranberry) River, then along the Nass. Horetzky describes a part of this journey on Jan 14: “We took to the river on a narrow ledge of ice upon which we very cautiously crawled two hundred yards having, on one hand, a perpendicular wall of rock, while upon the other the swift waters of the Nass seethed and boiled in a manner which actually caused blood to curdle as a single false step would have inevitably cost us our lives.”

Muskaboo accompanies Horetzky and his Hazelton guides to Gitwinksihlkw. Here native dancers entertain Horetzky: “…fifty men and women participated, nearly all masked…the motions were vigorous; and if not graceful, were, at any rate whimsical, and rather free; the men and women dancing alternately. There seemed to be a leader on both sides, who did his or her utmost to execute the most fantastic steps, which were accompanied by fantastic facial contortions and a monotonous chant, with which they kept excellent time.”

Horetzky and company walk to the village of Kitawn [no longer occupied]. The rain made walking “…execrable, the snow was saturated with rain and water covered the ice to a depth of several inches.” They were “…completely drenched and our snow shoes entirely used up from the effects of the water through which we had been obliged to wade for the last ten miles.”

Finding Fort Simpson

On Jan 20 Horetzky sets out for Fort Simpson [Lax Kw’alaams] with eight hired First Nations men and a very fine cedar dugout canoe “of a most graceful mould, intended to stand a rough sea.” For the miles of partially frozen river before they reach the open seas, the canoe is mounted on a roughly constructed sled to be pulled over the ice.

The group experiences three wet, stormy days and nights in which “…heavy gusts followed each other in rapid succession, driving the pitiless rain, which soon changed to sleet and snow …every now and then a terrific gust would threaten to blow fire, tent and everything into the water. Camp making on the sea coast in the midst of a pelting rain is a very different affair from the same operation in the interior, and oh! How I wished for a temperature of twenty or thirty degrees below zero.”

Finally, on Jan 23, 1873, Horetzky and his guides pull the canoe onto the muddy beaches of Fort Simpson [Lax Kw’alaams]. “Several miners, on their way to the Omenica via the Nass, curious to find out who we were, stood at the beach where we landed, and in answer to their inquiry as to where we came from, they received the laconic answer, ‘Fort Garry’[Winnipeg]. A stare of incredulity was returned.”

The final outcome

Despite the winter season, the unknown route and a motley crew of guides, Horetzky successfully journeyed from Fort Edmonton, Alberta to Fort Simpson (later called Port Simpson), BC—well over 1,000 kilometres in less than five months. Upon his return to Ottawa in March, 1873, Horetzky was an outspoken advocate of the Peace River Valley and the Pine Pass as the best route for Canada’s first transcontinental railway. The government disagreed, and the Canadian Pacific Railway was built through the Kicking Horse Pass to southern BC. Later, the Canadian National Railway constructed its line through the more northerly Yellowhead Pass.

Before making a permanent home in Ontario, Horetzky returned to BC to survey the north coast in 1874 and the Homathko Valley in 1875.

Horetzky died in 1900, leaving behind a stunning legacy of historical photographs and journals—and a little tributary of the Kemano River that he was bold enough to name after himself. Mount Horetzky, north of the Babine River, was named in 1938 by the Geological Survey of Canada to commemorate the explorer.