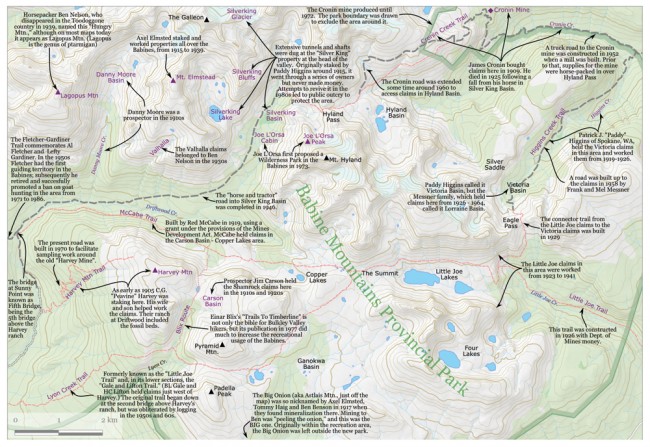

A Graphical Guide to Joe L’Orsa’s ‘History of the Babines’

In 1990, Joe L’Orsa wrote a 29-page typed manuscript detailing the “History of The Babine Mountains Recreation Area.” It was an extensive collection of historical facts, assembled to bolster the argument that the area be made into a park. For the Babines were not yet the park we know today. At that time the Babines were a Recreation Area, and park designation was still teetering on the slippery brink of government approval. It would not come for nine more years, after the completion of the Bulkley LRMP process, and, sadly, after Joe’s death.

In a sense, Joe spent his life researching this manuscript. Much of it was drawn from his personal knowledge: his father, Fort L’Orsa (who is buried in Silverking Basin), was a horsepacker and logger who built trails and delivered supplies to miners in the Babines, and Joe grew up in and around those mountains. It was also drawn from reading numerous annual reports from the Ministry of Mines.

On this map I’ve attempted to relate much of the information he collected about the many distinctive names in the park. Most of them derive from the miners and prospectors that worked the area in the 1920s. Prospectors were active in the area before the railway came through in 1913, with the first recorded claims in 1905 on Harvey Mountain. The McCabe Trail, for example, we find is named for Red McCabe; the Fletcher-Gardiner trail for Al Fletcher and Lefty Gardiner; Higgins Creek for Paddy Higgins; and the Cronin Mine for James Cronin.

There was constant fever about the mining potential of the Babines in those days. It frequently was imagined that rail access to the valley, and then road access, would make those mineral deposits finally worth mining. Despite the hype, only the Cronin mine ever made any money. Nonetheless, money from the Ministry of Mines, and money invested in claims that never paid off, built many of the trails we enjoy today.

The park boundary we know derives from a line Joe drew in 1973. In proposing a park, he circled the area at the 3500’ elevation level, which was considered the upper limit of merchantable timber—he knew he needed to make the proposal acceptable to logging interests. This line became first the outline of an “integrated management unit” and later a “recreation area.” When in the early 1990s park designation looked imminent, the Ministry of Mines assessed the recreation area and suggested that “extreme mineral potential” remained at the Big Onion (Astlais Mtn.) and the zone around the Cronin mine. These were both then cut out of Joe’s original line, and, in compensation, other areas west of the original line were added in.

By the way, if anyone knows who “Little Joe” was, after whom Little Joe Creek, the Little Joe Lakes, and the Little Joe Trail were named, let me know!