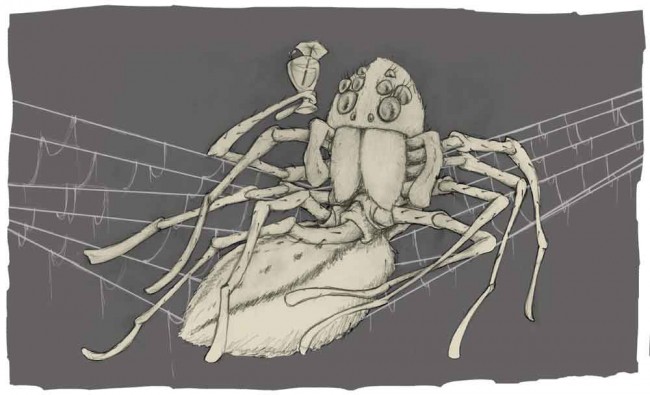

Photo Credit: Facundo Gastiazoro

Bug Bonanza: Is climate change impacting northern spiders and insects?

A slight movement on my sleeve catches my attention: A spider—the size of a nickel. Yeow!

As I fling back my arm, the spider goes flying. “Where did it go? Where did it go?” I ask Ken as we search the small cabin. That night, with Spider Godzilla still loose, every brush of the sleeping bag against my face causes me to snap awake.

For someone who collects invertebrates for the Royal BC Museum and has spent a lifetime working to preserve biodiversity, my reaction is a bit embarrassing. Last summer, though, there was a bonanza in spiders. Not only were there more spiders, there were bigger spiders with large, tough webs that spread between the trees like cotton doilies: “Climate change,” one of the old-timers said while we ducked several super-sized, eight-eyed predators hanging across the path to his woodshed. “Going to be nothing but huge spiders the warmer we get.”

Curious as to whether this spider invasion is actually an early vanguard to a warming climate, I contacted the Entomology Division at the Royal BC Museum. According to museum research associate Robb Bennett, the insect and spider numbers we experienced during last year’s warmer and drier summer were actually closer to normal invertebrate population levels.

The last few years, northern BC has had cool, damp weather, especially in the late spring and early summer. Who can forget the summer of 2011 with its non-stop rainfall and cold temperatures? Invertebrates, such as insects and spiders, are cold-blooded—that is, their body temperature reflects the temperature around them.

“Many insect and spider species suffer significant mortality and lowered reproductive capacity during cool, wet weather,” Bennett says. The outcome is that locations with warmer, drier climates support more invertebrates than ones with cool, wet springs and summers.

According to Bennett, last summer’s large spider numbers, as well as attention-grabbing insects such as wasps and yellow jackets, were more an effect of local weather conditions than long-term changes in climate. In the West, our summers oscillate between drier, continental weather conditions (La Nina air flow patterns that blow from the continent to the ocean) versus oceanic-driven weather conditions (El Nino wind patterns that blow cool, moist ocean air against the west coast).

If you are a spider, this means that some years are cool and wet, with low insect numbers and slow growing conditions, while other years, such as last summer, are warm, dry and full of flying insects. Hot summers provide the perfect conditions for spiders to become large and intimidating.

Bigger bugs?

But if climate change is occurring globally, what will happen to northern BC spiders and insects? Are we looking forward to a change in the number of bugs in our backyards and forests? Climate change models suggest that we are. As average summer temperatures increase in the northern interior, insect and spider population sizes will increase and species’ ranges will move northward and to higher elevations.

The effects of climate change are less clear for the north coast. Some models suggest that the region and its associated inland valleys may experience wetter, cooler summers. If this happens, spiders and insects will likely decrease in numbers and diversity.

These shifting weather patterns can set the stage for new, introduced insects, as well as population explosions of native species whose growing conditions exceed their natural restraints. In the last 30 years, we have had both natural and introduced plagues of aggressive insect populations. The mountain pine beetle is an example of a native insect whose expanding population has had major negative impacts on the normal ecology of northern BC.

According to research by the University of Northern British Columbia and the Mountain Research Station at the University of Colorado, warmer summer temperatures most likely led to stress on pine trees, making them more susceptible to insect attack. The warmer summer temperatures, combined with less severe winter temperatures, allowed for better beetle survival. All of these factors contributed to the ability of the mountain pine beetle to spread rapidly throughout interior forests and expand its ranges northward and eastward.

Similarly, introduced insect species can also become significant problems in response to climate change. An example of a non-native species spreading throughout wild crab apples and domesticated fruit trees in the Terrace-Kitimat area is the apple ermine moth. First detected in Kitimat in 2011, and assumed to have been brought by nursery plants from southern BC, this tiny but voracious European moth has spread up the Kitimat-Lakelse valley to devastate fruit trees in the Terrace area.

Building thick webs to protect themselves from predators, an infestation of the apple ermine moth caterpillars can strip a tree of leaves in a matter of days. Last year’s warm summer allowed it to spread from the localized infection in Kitimat into Terrace’s agricultural area. If the northern climate becomes warmer, then invasive species such as this can spread even farther north.

Will spiders be similarly affected?

Warming trends could affect both spiders’ survivability and the amount of food available for them. There are close to 800 spider species known in British Columbia, with probably another 200 waiting to be recorded. Of these, the majority are valuable members of the province’s ecosystems, keeping local insect populations in check and providing food for predators, such as birds and amphibians. If their ranges expand, these spiders are unlikely to upset the ecological balance of ecosystems adjusting to climate alterations.

From a human perspective, though, shifts in spider abundance attract a lot of interest. Some have strong emotional reactions to spiders. Other people are concerned with spider bites.

According to Bennett, spider bites are rare and only one spider in BC, the western black widow, has any potential for significant health concerns. Fortunately, this species is limited to the southern part of the province.

Other spider species of human concern are also still limited to southern British Columbia. The introduced giant house spider, terrorizer of basement-suite renters in Vancouver, and the hobo spider, falsely accused of causing health issues, have never been detected in the North and have a long way to expand ranges before they might occur in this part of the province.

Will climate change affect the abundance of spiders and their insect prey in northern BC? Yes. Although variations in weather conditions from summer to summer will have the most impact on annual spider numbers, climate change will slowly, imperceptibly alter which spiders species occur in any one area and whether they thrive there.

As you lie in your sleeping bag this summer, watching a large hairy wolf spider attack the bugs at the peak of the tent roof, you may be given to pondering a future full of spiders—big spiders—in a warming world.