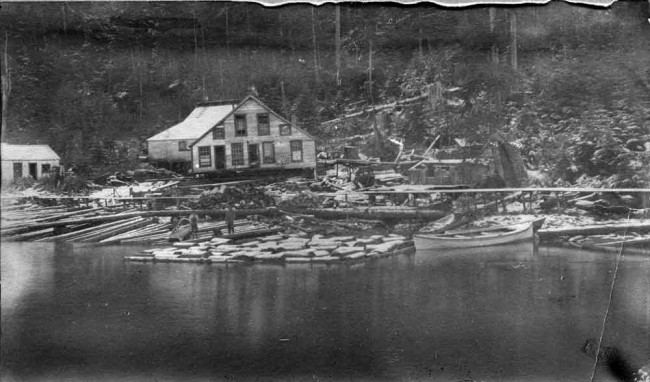

Photo Credit: North Pacific Cannery Archives

Diversity, adversity and prosperity: A colourful history meant ups and downs for BC immigrants

In the mid- to late-1800s, northern BC’s non-aboriginal population exploded. Newcomers were attracted to the region’s natural resource wealth, particularly its gold. What we know of that era today usually relates to the people who dominated that society: white Americans and Europeans. Yet, the population was culturally diverse and the historic sites and stories that reflect that diversity are worth exploring.

Journeying into the harsh northern wilderness during the Omineca and Cassiar gold rushes in the 1860s and ’70s wasn’t easy. As they had done farther south, Spanish American (predominantly Mexican) packers used their skills to lead mule trains loaded with supplies across long distances. Many early Spanish American packers were mestizo; they were of both aboriginal and European descent and considered outsiders by BC’s colonial establishment. However, they were vital in providing supplies to remote outposts.

While men from other cultural backgrounds learned the packing trade, the techniques and terms the Spanish Americans introduced endured. The pack train leader, for example, was known as the cargador and his deputy was the segundo. The Fort St. James National Historic Site was an important northern centre for packers and, in 1893, the Hudson’s Bay Company leased its pack train operations between Fort St. James and McLeod Lake to Sanchez and Aguayo, two Mexican former employees.

An invitation

During the Fraser Gold Rush of the 1850s, BC’s first governor, Sir James Douglas, invited black Californian residents to settle in the province. Thousands of white Americans entered BC at that time, bringing with them not only dreams of riches but an idea that terrified Douglas: the annexation of this abundant land to the United States.

Douglas believed black Californians would be more loyal to his young province because the British had already abolished slavery (while California was technically a “free state,” its laws were nonetheless oppressive for non-Europeans). Douglas himself was mixed race, born in British Guiana (present-day Guyana) to a Scottish father and a Creole mother, and he had a brief but eventful stint working for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort St. James earlier in his career.

The impact of Douglas’ invitation stretched far beyond the Fraser Gold Rush. John Robert Giscome was born in Jamaica. After spending time in the California goldfields, he joined the California black migration of 1858-9. Once in BC, he met his prospecting partner Henry McDame, who was originally from the Bahamas and had also accepted Douglas’ invitation.

Giscome’s most famous discovery occurred by chance, when a First Nations guide showed the pair an ancient shortcut across the Continental Divide—a trail that connected the Arctic and Pacific watersheds. They were the first non-aboriginal people to travel the route and Giscome wrote of the journey in the Victoria Times Colonist. The trail eventually became known as the Giscome Portage and it was widened into a wagon road in 1871 during the Omineca Gold Rush. The trailhead is located near the Huble Homestead Historic Site, approximately 45 km north of Prince George. Though the homestead was built years later, the site features interpretive information on Giscome’s life.

Giscome’s partner also left his mark on the maps of northern BC; McDame Creek, for instance, sits on a Dease River tributary. McDame struck gold there in 1874 and his discovery helped spark the Cassiar Gold Rush. Three years later, BC’s largest gold nugget was found in McDame Creek.

Chinese roots

The Cassiar District and the Chinese have a particularly interesting connection. Theories have circulated suggesting the Chinese reached the Americas before Columbus, possibly even before the Vikings. While these claims have been widely disputed, two intriguing discoveries have been made in the Cassiar. In 1882, a string of ancient coins was unearthed in an area that appeared to have been undisturbed and in 1885 more coins were found in a vase wrapped in the roots of a tree that was about 300 years old. Lily Chow takes a broader look at Chinese migration to northern BC in her book Chasing their Dreams: Chinese Settlement in the Northwest Region of British Columbia.

Barkerville emerged as a major centre during the Cariboo Gold Rush and today the National Historic Site offers the province’s best gold rush interpretation. A historical tour of Barkerville’s Chinatown highlights the reasons so many Chinese men emigrated and the cultural and political values they brought with them. Most Chinese migrants came from the Pearl River Delta. Typically, a Chinese company would pay for the passage of impoverished men to British Columbia and, if they survived the horrific conditions onboard the ships, it would take years to repay their debt.

In northern BC, as in other parts of the province, white miners did their best to exclude the Chinese, perceiving them to be a threat to their own ventures. Nonetheless, the Chinese successfully worked sites that had been abandoned by the white miners and explored other areas. During the Omineca and Cassiar gold rushes, the Chinese camped at their claims during the summer and in the off-season lived among the white people in nearby communities like Hazelton, Telegraph Creek and McDame Creek. A few places were named after Chinese miners; Ah Lock Lake near Manson Creek, for instance, is named after a miner who worked the area during the Omineca rush.

Multicultural cannery

On BC’s west coast in the mid- to late-1800s, a different kind of natural resource was being exploited: salmon. The North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site (22 km south of Prince Rupert) was founded in 1889. By this time, Japan had eased its strict emigration policies and men from Japanese fishing villages were among the cannery’s first employees. The workers lived onsite during the fishing season in a village that was divided, like their jobs, along racial lines. Operations were managed by the Europeans, who also worked as fishermen alongside Japanese and First Nations employees. The Japanese proved to be skilled net menders, while jobs on the cannery line were given to the First Nations and Chinese, and the Chinese cooked.

While most of the original village buildings have been lost, a Japanese bunkhouse that was built in 1930 is very similar to the structures that existed in the late 1800s. The Cannery Life Tour at North Pacific Cannery provides an in-depth view of the different cultural groups that worked at the cannery.

The experiences of early migrants to northern BC varied greatly. They faced hardship and discrimination, but a few also prospered. Many eventually returned to their homelands, while others settled and started families in Canada. Their stories construct a more complex idea of what life was like for the diverse group of people who helped build BC’s foundations.