McGillivray’s Map

Simon McGillivray, a trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company, was the first outsider ever to visit “the Forks,” the place where the Skeena and Bulkley rivers join, and later the site of the town of Hazelton. Based out of Fort St. James, he was shown the way west to the Forks in 1833 by local people from Old Fort Babine.

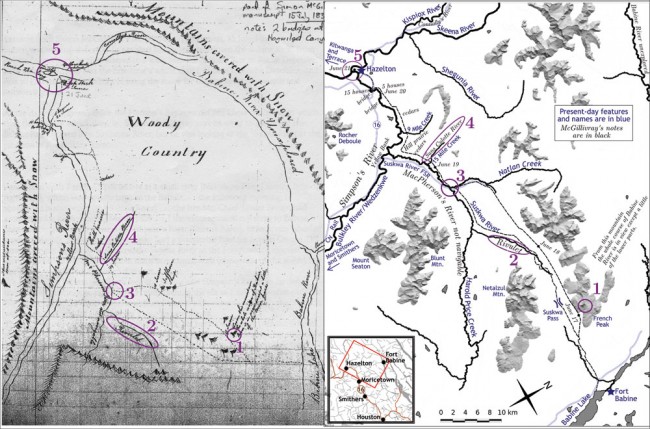

But what route did they take? Fortunately, he left us a hand-drawn map, located in this century by Alan Pickard in the HBC Archives in Winnipeg. It is possibly the oldest European-style map of the Bulkley Valley.

And what a fantastic map it is! Hand-drawn, with mountain notations and wavy rivers, it tells of an alternate geography—one in which the main route of travel neatly connects Hazelton to the outlet of Babine Lake, two locales that today are a dusty, circuitous, three-hour drive apart. For probably thousands of years, until the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway came up the Bulkley River, the primary way for people and goods to travel between the coast and the interior was through the Suskwa Pass and over to the northern end of Babine Lake. A major pack-trail upgrade was undertaken along this route in the 1870s, and hundreds of gold-seekers headed to the Omineca this way.

We can match McGillivray’s map with many features we recognize today. French Peak (1) is probably where “From this mountain the whole course of Babine River is in view except a little of the lower parts.” “Rivulet” (2) is the upper part of the Suskwa River as it flows from Suskwa Pass. (McGillivray calls the Suskwa River “MacPherson’s River”.) The meeting place (3) where he touches the Suskwa on both his outward and return journeys is perhaps the same place where at Km 15 the Suskwa Forest Road crosses the river today. The “Sans Culotte River” (4) is Fifteen Mile Creek near Hazelton. (Sans Culotte was a term for the working-class folk fighting in the French revolution some 50 years before McGillivray drew his map.) The Forks itself (5) stands out as the confluence of two major rivers.

I have to admire how closely the shapes of McGillivray’s hand-drawn rivers echo the actual geography measured today with GPS and satellite photos.

One thing McGillivray knew he was looking for was Simpson’s River, a big river that met the ocean near an HBC post called Fort Simpson, at today’s village of Lax Kw’alaams just north along the coast from Prince Rupert. British map-makers incorrectly showed Simpson’s River flowing out of Babine Lake, and coming out at the mouth of the Nass. No one they knew had ever actually been down that river. When McGillivray saw the Bulkley, he thought he had found Simpson’s River, and labelled it so, in his beautiful handwriting, on his map. He also assumed the big river coming in from the north to join it at the Forks was the Babine. He never knew this was in fact the Skeena, the major river that collects the Babine, among many others, on its way to the sea.

McGillivray, whose mother was a métisse and father an HBC partner, had one foot in the world of European culture and the other in native culture. He travelled in Europe, but was also at home in the wilder lands of western Canada. He formed a crucial link because he could live with local residents who knew where everything was, then pass on what he learned to HBC traders and map-makers.

Sadly, the information on this map never made it out of the Hudson’s Bay Company offices. More than 10 years after his journey, the Forks and the Skeena were still absent from both British and American maps.