Photo Credit: Facundo Gastiazoro

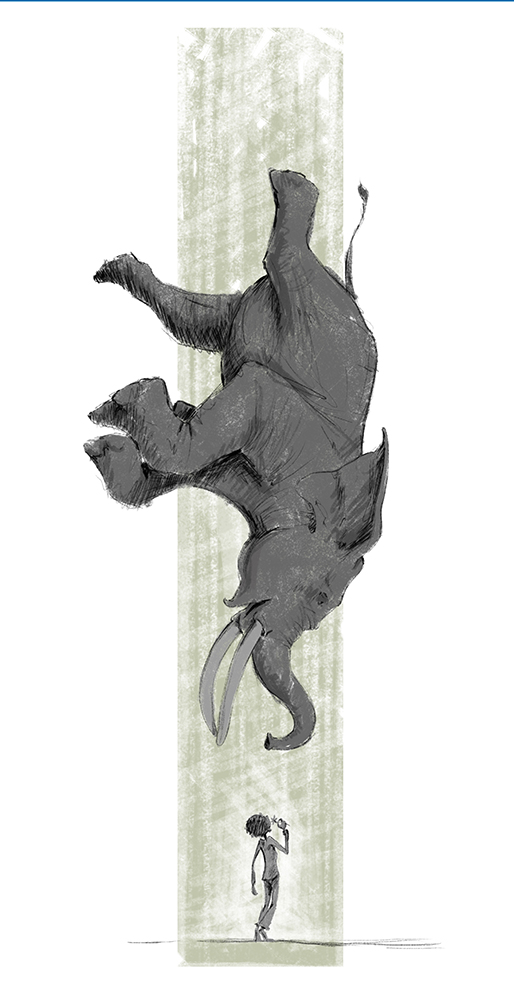

Optimism in the Face of Impending Disaster

Standing inside a disused beehive burner, shards of light bursting in through the holes where the metal has rusted out. The landscape used to be full of these round-nosed cones, churning out smoke and ash as they incinerated tons and tons of sawmill waste.

The smoke still comes. Wildfires now; worse than they were. Nature’s revenge. First comes a faint burning smell, and then the sky sinks into a murky haze. The haze gets thicker and creeps into our homes and our noses and throats, and we watch the colours of the online air quality index change from blue to yellow to pink to red. Somebody says it’s not that bad; it’s like this all the time in Beijing.

Sometimes it’s hard to be optimistic about our future. Our hopes for our descendants are retreating with the glaciers and the reluctance of politicians and corporations, and even ourselves as individuals, to act. Yet, despite the many issues our society faces, environmentally and socially, there are reasons to remain hopeful about the future.

Northern optimism

Vince Prince is the CEO of the Nak’azdli Development Corporation, which deals with 18 reserve lands in the Fort St. James area. Balancing economic demands with environmental concerns and traditional uses of the land is a key aspect of his job. The corporation is currently involved with an agricultural research project and the development of a greenhouse that it hopes will provide both jobs and local food year round.

“Agriculture is something that we decided we wanted to pursue. People are excited about it. They’re really excited about not having to get, you know, cucumbers from Mexico.”

Prince says he’s also very hopeful for the future prospects of young Aboriginal people in the region. “I get to see more and more taking the opportunity in terms of education and apprenticeships.” He jokingly complains that they have trouble getting enough band members to fill the management jobs they have, not because there aren’t enough qualified people but because they keep getting scooped up by other companies who pay more. There are now two doctors from the territory who are completing their residencies in Prince George, one of whom is planning to return to set up a practice in Fort St. James.

Julia Dillabough is the president of the Quesnel Pride Society. She believes visibility is critical to the future of gay rights, and small-town pride parades such as the one started in Quesnel three years ago help raise awareness and acceptance. “It’s amazing how Quesnel comes out to support the Pride Parade,” she says, commenting on the support they’ve received from local businesses, Mayor Bob Simpson, and MLA Coralee Oakes. “There’s support from every direction. For the most part, if somebody doesn’t agree with it, they just leave it alone and they go about their business.”

Dillabough expects that the increased visibility of LGBTQ people in smaller communities will have an impact on the number of sexual minorities choosing to leave big cities. “They’re seeing these more accepting pride parades in the North. They want to get out of those larger centres because they like nature, they like hiking, they want what everybody else wants—affordability—and that’s what we have.”

Inspired by the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, pediatrician Dr. Marie Hay is actively working toward creating a Peace and Reconciliation Centre for the north, based in St. Michael’s Church in Prince George. “I think this is, on a human level, the biggest question for northern BC. The quality of the relationship between First Nations and settlers.”

Though the idea is still in its infancy, the space available for the centre is already being used by a support group for women residential school survivors as well as other groups that need a space in the community but can’t necessarily afford one. Hay’s vision for the centre is that ultimately “it would be a centre of education for not just First Nations and settlers but for immigrants and refugees, for rich and poor, for marginalized individuals.”

Within the medical field, there are a wide range of developments that will hopefully lead to improved patient care in the future. According to Hay, “The issue of trauma in the health of human beings is as massive as climate change to the Earth and we’re only just beginning to realize it.” The findings of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study are shaping new approaches to the issue, and with increased understanding and education around trauma-based medical practice, Hay believes many patients will receive more effective treatment.

Technology is already helping medical professionals like Hay assist patients in remote and rural areas through tools like Telehealth (which facilitates remote consultations via local health centres) and Confident Families (which provides remote support for families with children suffering from behavioural issues). The expansion of services such as these and other advances in the medical field will no doubt make a big difference to many northern residents.

Crucially, Hay believes it isn’t technology that has the power to make the biggest difference to our lives in the future. “Really what is going to improve quality of life for people in the north are the social determinants of health—fresh, safe water, fresh, safe food, food security, housing security—these kind of things are what’s really going to determine and improve the quality of life for people in the North.”

Environmental awareness

Ultimately, our future prosperity comes back to our environment. As with social change, awareness of the problems and what we can do about them is at the heart of any hopes for altering our course. Karen Mason-Bennett, program coordinator with the Northern Environmental Action Team (NEAT) points out that, “When you understand the issues, the decision to change your behaviour becomes easier.” One of NEAT’s initiatives, Food Secure Kids, teaches students about the importance of food security in the North. Mason-Bennett hopes that by encouraging young people to value locally produced food, they will support those systems in future, and perhaps even help generate a push for policy change at the government level.

Being more aware of our own actions as individuals is a big step in the right direction. We’re all guilty of buying things we don’t actually need, and most of the time, need versus want doesn’t even factor into the equation. As Mason-Bennett explains, “Actually taking a moment to think about what we are doing and whether it’s important or necessary, could be the most impactful environmental movement ever (and it might clear that pesky credit card debt too!).”

She also believes that northern communities are very well positioned to benefit from the development of renewable energy sources in the future. “The same geologic forces that created oil and gas provide great geothermal potential, and there’s no shortage of wind! We’ve got two solar cities, and Hudson’s Hope is blazing a trail with their municipal solar installations.”

There are many initiatives happening in our communities that are designed to help us contribute to a better future. One such program is Change Day BC, which Hay is involved with. Healthcare professionals and members of the public are encouraged to visit the website before this year’s Change Day on November 17 to make a pledge that will improve personal, family or community health (changedaybc.ca).

Future connections

Mason-Bennett’s advice for paving a path to a better future? Stop. Breathe. Connect. “Stop buying stuff. Stop wasting things. Breathe deeply. Breathe in clean air and realize that we are so lucky to have that luxury. Connect with your family. Connect with your kids. Connect with the world around you. Talk to your neighbour. Go to the park. Start a garden. Go for a walk. Play. Find something that makes you feel fulfilled and invest time in yourself. Make memories.”

Prince hopes our future will be values-based. “Have respect for the land. Have respect for the animals.” These values, he explains, should be a core part of our being, not quickly disregarded when it is convenient. “The culture is something you carry with you every single moment of your life.”

Dillabough says in the future there will be “a bunch of gays and lesbians running around with kids. I definitely foresee there being more families, more networks. Right now we’re at a time where gay marriage is just being accepted. It’s being legalized in more and more countries; granted there are some that are trying to claw it back. But I think that trans people will have more acceptance, especially within the North.”

Hay, who will be retiring next year after a career in medicine, says she’s now at the age where she can look back and think about what is really important in life. She believes “the creative force of love, inside of us as individuals, inside our families and our communities is the key to the wellbeing of our human race.”