Sadie’s Bone

On a small strip of damp grass just off the courtyard, Sadie dances. Her lips mouth the 1-2-3 rhythm of a silent dance routine. Her pink legwarmers and dirty white sneakers bounce out a beat. Sadie is leaping and spreading her arms wide, open and closed, open and closed. Water flicks off Sadie’s wet shoes and falls on the grey sidewalk.

A nurse wearing white stockings swishes past Sadie and walks to the bench where Sadie’s parents sit. The nurse tells her dad that he has just five more visiting minutes left; he has a group session. Greg nods. He has a brown paper bag squashed on his lap and is eating the take-out Sadie chose for him. A Chinese noodle is stuck in his black beard.

Beside Greg sits Sadie’s mom, Brenda, who manages to pick at the Chinese food despite her hunched-up posture and cinched-together arms. Brenda’s left foot vibrates as if it wants to cut loose from her and hop away.

Greg watches his young daughter do gymnastics, her floor routine, waving her right arm as she leaps and rolls across the damp grass. A track of moisture is seeping a wide line on Sadie’s shirt. Greg watches the tumbling intently and wonders if he can learn to braid in one day. There is just one day left here and he wants to surprise Sadie with something. Greg thinks that if his daughter’s hair was back in one thick braid instead of falling in wads down her back with some thin strings falling in front of her ears she may stand a chance; she might look like a girl that could half afford a real dance class.

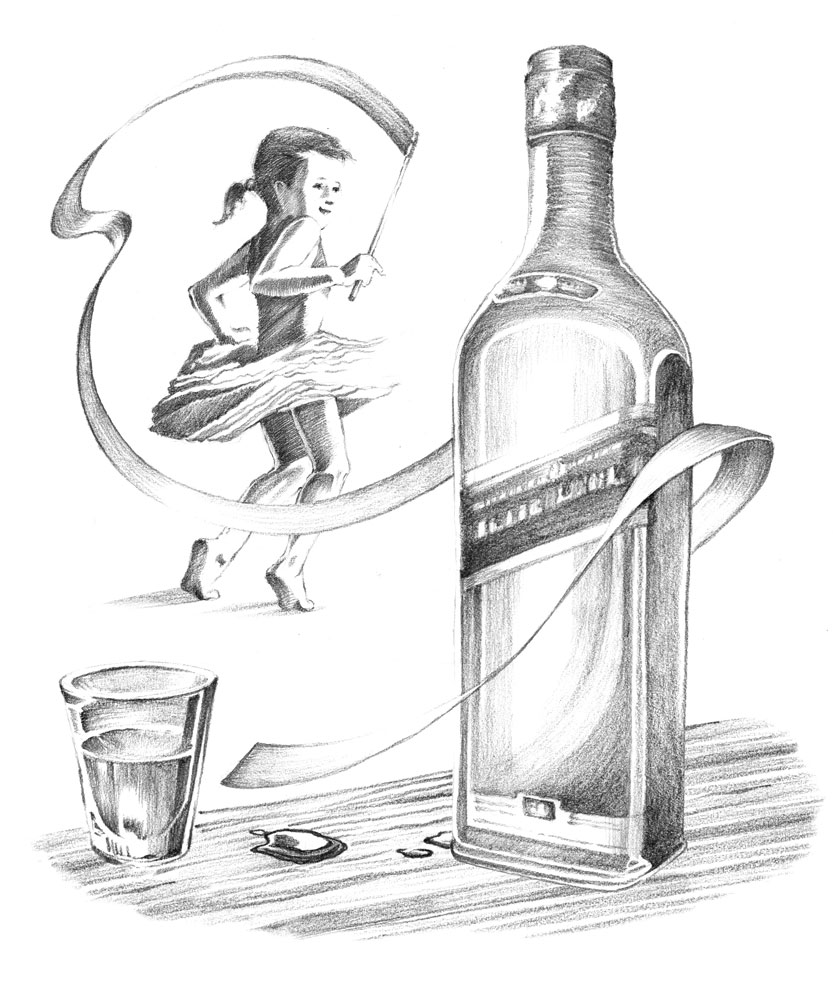

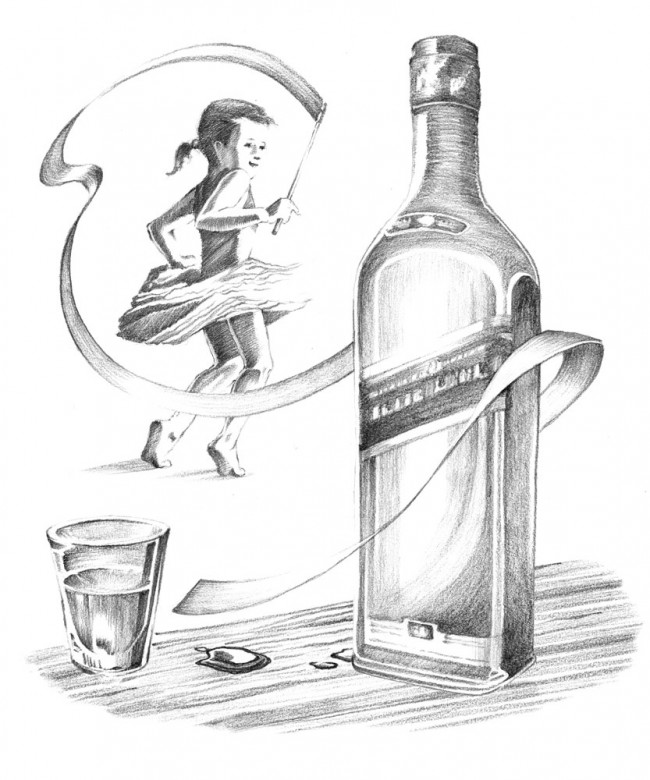

Sadie holds one arm out straight and tells Greg to imagine a stick in her hand, a long stick with a pretty dance ribbon. He sees it perfectly, imagines a brilliant red ribbon with gold edges, a Johnny Walker ribbon. He watches his daughter and her pretend dance ribbon and looks sideways at his wife. Brenda sucks at her teeth, adjusts her mirrored glasses and looks at her car parked in the empty lot. Sadie points a small sneaker and flicks her wrist toward her parents on the bench; Greg hears the imagined ribbon snap like a buggy whip.

Brenda cracks open her fortune cookie as blue jays drop out of a low-slung maple tree and strut around a garbage can. Sadie flips and bows, one small hand pressed on her back, the other hand on her belly. Greg stands, letting the paper take-out bag fall to the sidewalk. He claps his big hands. He smiles at Sadie. He rubs his hairy knuckles and thinks again that he really needs a drink. But Sadie stares at Greg like she can read his mind and Greg nods at her. With a proud, straight back Sadie bounces across the grass to start the routine again. Brenda frowns at her fortune, folds it once down the middle and picks the space between her front teeth with it. With her other hand she compulsively clicks the silver clasp of her purse.

They look at each other. Greg lifts his chin in the direction of Brenda’s bouncing foot and asks if she is alright to drive. Brenda nods, taps her wrist where a watch might have been, stands up and walks toward the parking lot. Greg waves Sadie over. Sadie widens her brown eyes, lifts her eyebrows and touches a finger to her own chin. Greg mirrors her and swipes the food out of his beard. They hug, Greg shakes his beard in Sadie’s small neck and she wriggles and laughs. “See you in one more sleep,” he says. She runs to the parking lot where Brenda has the Datsun idling. Sadie does a perfect cartwheel and doesn’t have to look back to know her dad is watching.

Back at their apartment, Brenda does Greg a favour and continues her 60-day effort of cleaning the apartment of all drugs and alcohol. She is drinking the last fingers of dark rum from the bottle while Sadie practices handstands against the living-room wall. Brenda has her first clear thought in weeks and is reminded of her childhood dog, a beagle named Oscar. She remembers he was an eager dog, balancing on his hind legs for milk bones, leaping into the air, racing underfoot, chewing table legs and ripping couch cushions. She remembers her mother, in an effort to amuse the dog, wrapped a beef bone in many layers of newspaper and left it for the dog to tear apart whenever they left the house. They would come home to shredded newspaper all over the house and the dog splayed out on the linoleum happily chewing his bone.

Brenda knows then what she has to do. She moves through the apartment with a controlled pace and a slow focus she had forgotten she possessed. She rummages through an old sewing basket. In a box of Christmas decorations that haven’t been opened for several winters Brenda finds rolls of wrapping paper. She does what she has to do.

Later, she checks to make sure an extra toilet paper roll is close to the toilet, that the dull scissors and construction paper are on the floor of Sadie’s bedroom. She goes to the kitchen, stands on the counter and stashes all the matches and kitchen knives out of reach.

From the countertop she pauses and surveys the apartment. There is a record player, a potted plant and an ashtray. There are open curtains and a jammed-shut patio window that looks out to the street. There is a young girl on an old couch looking at an Archie comic. There is a small kitchen window looking out at the brick wall of the next apartment. From the shadows stretching across the wall she can tell that the sun is going down. It’s late in the evening.

Brenda climbs down from the counter. She sniffs the milk jug, then pours milk into two tall glasses. She labels the glasses with permanent marker, 1 and 2, and balances them on a low wire shelf in the fridge. With the same marker she labels the bananas, 1 and 2. And the wax-paper-wrapped peanut-butter sandwich stacks, 1 and 2. Then, while the sun is setting and Sadie is sitting cross-legged on the carpet listening to the Smurfs on the record player, Brenda picks up her purse and leaves.

One day later, in the dusk of early evening, Greg steps off the city bus in front of their apartment. All the lights are on and the patio curtains are open. He sees his young daughter dance across the living room. Greg thinks they must be up late, waiting for him. He wants to know why Brenda hadn’t shown up to drive him home on his last day.

Greg opens the apartment door and Sadie leaps across the linoleum and into his arms. She won’t let go of him. Her arms are a vice under his beard, around his neck. Her little legs are pinching Greg’s middle. Sadie cries. Greg realizes something is very wrong. He thinks he has to go to the bathroom, has to drink and has to find Brenda. He ignores the first two thoughts and, carrying Sadie, runs around the small apartment. He calls, just once, for Brenda.

All over the floor—in the kitchen, the hall, the bathroom, Sadie’s room—are layers of crumpled wrapping paper. He collapses onto the arm of the couch, Sadie still clinging to him. On the floor amongst the paper is a long yellow ribbon tied to the end of a short stick. Sadie follows his eyes and tells him it’s new, that it was the surprise that Brenda left inside the big present.

She wiggles out of his lap, wipes the tears from her swollen, tired eyes with the back of her hand, then brightens and tells Greg she has been practicing a new routine. She stands by the record player in the corner of the living room, straightens her spine, positions her arms, points her ribbon stick at the water-stained ceiling and tells her dad that she has the first part all planned out but hasn’t figured out yet how it will end.

Illustration by Hans Saefkow