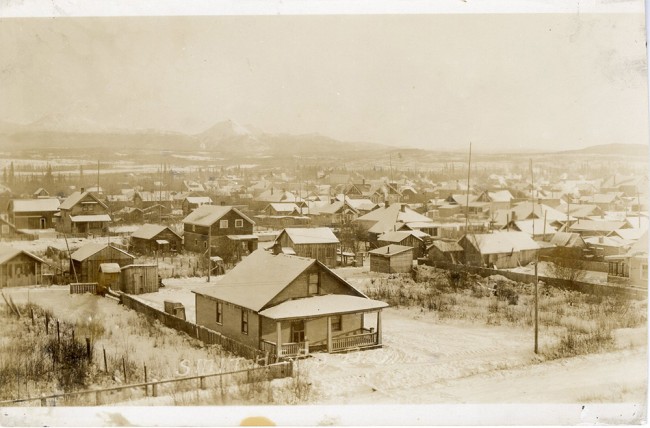

Photo Credit: Courtesy Bulkley Valley Museum

Shared Histories

We are all born into contrast. It’s evident in the constellation of freckles that dance across fair cheekbones, in the glistening river of highlights that cascade through dark curls. It is the gold that shines in ebony eyes, the strong jaw that hugs a soft smile.

These days, many of us celebrate our distinctions—those little contrasts that make us the masterpieces we are. But when traversing the paper trail of history, with its countless accounts of racism, intolerance, and genocide, it is painfully obvious that not every difference is lovingly accepted. Even Canada, the quiet nation acknowledged as an international peacekeeper is stained by a long history of discrimination that darkens our past; we were not always the true north, strong, and free.

We pried First Nations children from their parents’ protective grip and forced their small frames into rigid expectations, blind to the inky fear that seeped into their eyes. We ignored their tradition, stomping fallen feathers into the dust as black and red regalia fluttered hopelessly in the wind. We sentenced them to silence, and then moved on with apathy and ignorance.

At best, this part of history was a featherlight touch on our collective conscience; a brush of familiar wind in our ears that hissed the parts of the harrowing stories we declined to hear. As time marched on, so did the silence. It painfully stretched, and stretched, and stretched.

And then it broke.

Today, we live in a world where purposeful apathy and ignorance are among the most undesirable qualities a human can possess. Canadians are becoming more interested and more informed of our entire history, learning the bloodshed, discrimination, and hatefulness that left such a stain on our famously peaceful nation. At the same time, First Nations individuals and communities are gathering up the heavy strands of their pain and weaving it into the remaining silence to patch the holes in our history—and to finally hear their stories truthfully told. At the forefront of this reconciliation are published books, ink capturing these stories so they cannot be forgotten again. The local connection is almost always the one that resonates most clearly. Finally, the long history of the Witsuwit’en in the Bulkley Valley, including their efforts in the creation of the town, and the forms of discrimination they faced, are now forever encased in the freshly-printed pages of Shared Histories by Tyler McCreary.

McCreary says that the creation of this book was an enlightening personal journey. “I grew up living on Bulkley Drive and going to Walnut Park School with no real sense of the history of those places, or the history of contestations over what that town means, and who belongs in town. I understood there was a sphere of racism, but the particular history, the lineage of my family and its relationship to the history of racial dispossession, I didn’t know exactly.”

Now he is all too aware of the dark racial history that shadows Canada’s image as a multi-cultural, accepting nation. “I definitely think that we have lived in a world contoured by racial differences for centuries,” he says. “And I think it’s really incumbent upon us to think carefully about the legacies we inherit as a society with a long history of colour coding, and the way that that shapes structures of privilege and wealth, and disadvantage and penalty.

“If we want to get to a more just place,” he continues, “I think we have to work through the legacies we inherit and actively try to come to terms with and counter them, and then ultimately, if we want to build relationships that get beyond the colour lines, I think we need to talk seriously about the histories that have built those divisions.”

With a careful blend of artistic thoughtfulness and academic intelligence, McCreary paints an eloquent account of the history of the Witsuwit’en and settler relations in Smithers in the late 1960s. A contrast of rigid analysis and flowing oral histories move the subject of this book from the settling of Smithers and colonial displacement through to the end of Indiantown in the early 1970s. It’s not pretty. Fred Tom, one of the first First Nations children to attend the Smithers Public School, is quoted in the book. “Some [white settler children] were scared to touch us cause they thought we were lousy… They’d pretend to blow the fleas off themselves when they touched us.”

Although this book tells the story of their ancestors, when reading sections of Shared Histories, First Nations teenagers from Smithers say the experiences described are painfully similar to their own. Jordyn Morin, a recent high school graduate, says she experienced a similar form of racist taunting, the only difference being that the two events happened approximately 50 years apart.

“I did face a lot of discrimination from my skin and my colour,” she says. “A lot of people think that we are stupid, or we can’t choose our words properly, or because of our dental hygiene we’re ‘dirty’. A lot of times First Nations people don’t have medical care. When I was a kid, I had to dye my hair in order to kill the fleas because the flea medical stuff costs a lot of money."

Most of the discrimination by youth comes from a naive ignorance and an instilled fear of the unknown—two elements easily dissolvable by factual information. But when asked if the kind of truths that are present in Shared Histories are found in classrooms today, Morin said no.

Even the existing textbooks that touch on the subject “aren’t even true,” she protests. “They don’t have any elders who properly describe what really happened. To be more detailed you need an elder to describe what they went through and their experience.”

Shared Histories is a perfect antidote to local unawareness; it was written with the help of local elders, many of whom are quoted detailing their experiences. For 17-year-old student Jessica Weeres, seeing her history written down for her peers to learn from is exciting, and brings hope for a more inclusive future.

“Even though we have a different skin colour,” she says, “that doesn’t mean we’re different from white people. [This book] would help other youth to understand that more, which means that over the years there will be more people talking about it, and more people listening to it.”

It is important that this book—one full of personal stories from local First Nations—is available to students to help our youth understand the history of their hometown, and the pain that stems from racism. This way, there will be a generation raised by awareness, understanding, and acceptance.

There is pride in being First Nations that is growing here, throughout the North, and across the country.

“When my mom was in high school there was a lot of racism here,” says Morin, “but nowadays she’s proud to say her kids are accepted.”

Weeres also has proud memories of her traditional upbringing, one that was free of the historical constraints her ancestors experienced. “I remember when I was little,” she says, “I was four years old, I had this little regalia on, and I was dancing. I was so happy, because everyone was just dancing with their beads and their headdresses and their deerskin dresses. I just remember being so free. Feeling so happy, so free, like this is me. This is who I am.”

These words stand tall amongst history, carefully lifting feathers from the dust, and pulling beautifully handmade regalia tight around its shoulders. A familiar wind brushes by it, whispering of hope. If a young First Nations person is now able to breathe life into proud words for their culture, and if the descendants of those who once caused such pain are eager to listen, history is now becoming the contrast to the present.

Apathy is ground beneath the foot of interest, and it is ignorance that now flutters hopelessly in the wind. Silence lies broken in shards on the ground as books like Shared Histories, filled with truth, carve learning, acceptance, and understanding into the hearts of the nation.

Of course, we can’t pretend to be free of history’s clutches. The events it holds bled inky fear and scarlet pain deep into the parchment of Canada’s past, staining its historic paper trail, dripping down from trees already bowed with harrowing accounts of discrimination. It is a difficult thing to acknowledge that our history and national pride are darkened with hatred, but that is the only way to move forward. The painful stories of history are pieces we cannot rewrite, but human nature cannot stay still. Contrast will prevail, and from darkness comes light.

— Savannah Parsons