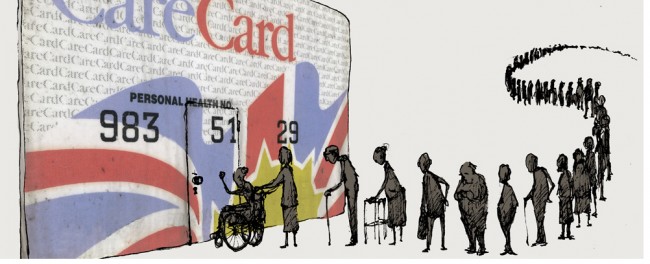

Photo Credit: Illustration by Facundo Gastiazoro

When parents age: A caregiver’s story

When Kim DiSensi of Telkwa, BC, took on the care of her 80-year-old parents she was thinking in terms of a two-year commitment. It turned out to be seven years and she is still coping with the fallout.

“Dad had pretty advanced dementia and Mom was in the early stages of liver failure,” she says. “They were in Nova Scotia and they really couldn’t be alone so they came to live with us.”

She, her husband and her parents had one good year together. Kim was 18 when she left home and she enjoyed getting to know her parents as an adult.

“The second year was not too bad and after that it was awful. Dad fell and hurt his back so badly he couldn’t stand. His legs would just collapse underneath him but with the dementia he’d want to go somewhere and try to get up. We were sleeping at the end of his bed to keep him safe.”

And, like so many dementia patients, his frustration and fear manifested as anger.

“It was so unlike him. He was always such a pussycat, never disciplined us as kids, but his whole mood changed,” Kim says. “He never actually hit anyone but he was a big man and he raised his hand a couple of times and I was afraid for Mom. He was so scared.”

Because of the risk he posed to himself and especially his wife, Kim applied for a bed for her dad at Bulkley Lodge, Smithers’ residential care home. She describes that process as a “nightmare” with assessments and reassessments and seemingly endless waiting.

“I was so desperate, two healthcare professionals told me to take Dad up to the hospital and just leave him there. I couldn’t do that but I also couldn’t deal with both his physical and mental illness at home anymore. And when he was admitted, I felt both sad and guilty, like I’d failed him.”

Her father died 18 months later.

About the same time, Kim’s mother’s condition began to worsen. She was incontinent and having trouble swallowing food and medications. Also, because the liver controls blood clotting, someone told Kim patients with advanced liver disease could “bleed out” due to internal hemorrhaging.

“That made things really hard. I would sleep with one ear open. I’ve been a worrier all my life.”

The unforeseen costs

Kim says one of the most frustrating things was having to spend an hour and a half feeding her mother a meal.

“Whenever I lost it, it was usually connected with feeding. And that’s awful because for someone who is bedridden, meals are very important. You want to make them as pleasant as possible.”

Eventually, while her dad was still living with her, Kim decided she had to quit work if she was going to care for her parents properly.

“I was eight months short of qualifying for my pension,” she says. “There were gaps in my work record so, after a total of 32 years working for different banks, I ended up with no pension.”

She and her husband also had to move into a smaller home with a more manageable mortgage because Kim no longer had an income and their costs were escalating.

“We had four to feed now and the heating costs are ridiculous when you’re caring for seniors. And we were paying for home support (health care workers who give showers, change linen and provide respite for family caregivers), diapers and nutrition supplements up until Mom qualified for the Northern Health palliative care program.”

Kim says the worry, lack of sleep, isolation, financial woes and, for her, the guilt over not being able to care for her dad through to the end, have left both her and her husband with ongoing health problems.

What would have made things better?

“More help a lot sooner,” she says. “Home care should be available free of charge for anyone who needs it when they need it. If the health system wants people well cared for at home, they need to support family caregivers as much as possible.”

Increasing strain on the system

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) states that between 2001 and 2010 the number of BC residents over 75 years old increased by 28 percent. During the same period, access to home and community care services, which enable them to remain in their homes and out of hospitals where costs range from $1,000 to $2,000 a day, dropped by 14 percent.

In its 2012 report Caring For BC’s Aging Population, the CCPA says access for people over 75 to home support in BC dropped by 30 percent, to residential care by 21 percent and to home care nursing by three percent. In the Northern Health region, access to home support for the same group dropped by 59 percent, to residential care by 26 percent and to home nursing by 30 percent.

“There are just going to be more and more cases like mine,” Kim says, “people who are sandwiched between their parents and their kids.”

There were some bright spots in Kim’s seven-year journey.

“I can’t recommend the adult day care program at Bulkley Lodge highly enough,” she says. “It was wonderful for Mom, huge for her. She lost all her friends when she left Nova Scotia and this program, for three days a week, gave her back a social life.”

Another boost for Kim was the local caregivers’ support group in Smithers. Started about four years ago, the peer-driven group meets monthly and provides family caregivers with an opportunity to share their frustrations, feelings of isolation and insights with each other.

“I cried from the moment the meeting started until I left,” Kim says. “Everyone was in the same boat. No one was judging me. They were there to listen. I could unload and it was enough to enable me to go home and do it for another month. It was a normalization process that validated all the stress.”

Letting go

During the last two years of her mother’s life, Kim got lots of help from family, friends and the local hospice society. But as the end of life neared for her mother, there were two issues troubling Kim.

“I couldn’t let my mother go. Making that decision was huge and I couldn’t do it without help. She was choking on her pills and sleeping almost 24 hours a day but I felt like I had to keep her alive, if only by strength of will.”

Kim went to see a doctor in Smithers who had been recommended to her.

“I asked her to do a home visit and she came the next day. She convinced me it was okay to let Mom go. I couldn’t do it alone. It was too much responsibility. And she even asked how I was doing. I didn’t think anyone was ever going to check in with me, to check on my health.”

Her other problem was unresolved grief for her father.

“I still hadn’t dealt with that. I couldn’t because I felt I had to hold it together for Mom. I went looking for a professional counsellor but I couldn’t find one. There’s just something about seeing your dad so vulnerable. It broke my heart and I’m still dealing with it.”

Would she do it all again?

“Yes, in a heartbeat,” she yes. “I know I made a difference in the quality of my parents’ lives. And I know I’m a more compassionate person now. But I don’t know that I would recommend it to anyone. You have to be really prepared and that includes knowing what you’re capable of.”