Notes from backstage

For a professional actor there are other places to live than Prince George, BC. Places like Toronto, Vancouver, Edmonton. Places large enough to support the actor in the world of theatre, film and TV.

But when the actor in question (me) is married to a librarian, and she (my wife, Nancy) decides, in 1992, that Prince George is the place to be, you do the husbandly thing and go along for the ride. In my case, the ride started in a beat-up U-Haul truck from Toronto—the centre of the universe—to the crowded landscape of too many mountains, trees, rivers, valleys, lakes, and pulp mills of BC’s Central Interior. (For a prairie boy, it can get a bit much.)

But with no professional theatre to work for, and no pool of actors with whom to work, the biggest challenge of all was to discern the cultural landscape of Prince George and how I could fit into it. There was a Symphony Orchestra, but I didn’t play the violin. There was an art gallery in a converted shed, but I didn’t paint. I had been spoiled, perhaps, living in centres with established theatres. But now it was back to square one. So I taught a few drama classes for kids, worked as a substitute teacher in the schools, and had an ongoing position as a stay-at-home Dad to my daughter.

It was a small miracle, then, when a year later I read in the Prince George Citizen that a fellow by the name of Ted Price and his business partner Ann Laughlin had come to town from the Lower Mainland to start a professional theatre. They came armed with a well-researched business plan and lots of guts. He was an actor and director who had worked across the country, including the Shaw Festival in Ontario. She was a former dental hygienist who later earned a degree in Arts Administration. Their theatre would be a regional theatre—the first regional theatre in Western Canada in 20 years. It would employ actors, lighting designers and stage managers from across the country in the heart of the Central Interior. Their dream would become Theatre North West.

At least that was the plan—the long-term plan. Initially, though, the theatre began in a small rented townhouse that served both as living quarters and office. Résumés from actors and grant application forms were in neat piles next to the sofa and coffee table and throughout the townhouse.

An important aspect of their plan was to get to know the community, the region, and their potential audience. And in a sense the first production mirrored this quest for knowledge. The Occupation of Heather Rose, by Wendy Lill, was about a nurse working on a native reserve who learns all about life in the north, and about a different culture. It was performed at various locations in Prince George—including a church—and toured the region to places like Williams Lake, 100 Mile House, Terrace, and many communities in between.

Ultimately, though, they wanted a permanent home and found one in a shopping mall. They converted a large bay at The Parkhill Shopping Centre in Prince George to include office space and a seating capacity of 100.

Newly settled into their new home, the 1995-96 season featured a line-up of four shows, ending with a production called The Wild Guys. Written by the pride of Fraser Lake—Andrew Wreggitt—the play featured four guys on a week-end hike into the wilds of the Central Interior. The show was so enormously successful, additional performances were added to meet the demand for tickets. At one point an actor had to leave the production because of a previous commitment, but was speedily replaced by another so the show could continue. Eventually the show did close, to allow enough production time for the next play.

The Wild Guys had it all: a well-written script, set in this area, and with a great premise. (You can’t go wrong with the premise of four city guys getting lost in the woods.) And, like the previous plays, it had high production values and terrific acting. (As one of the actors in this production, I admit to a slight bias here.)

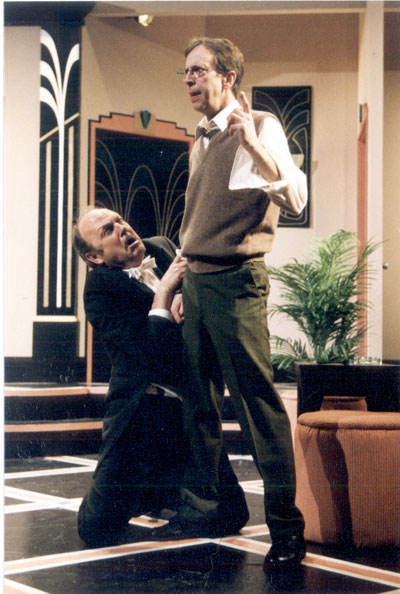

The 1996-97 season started off with another huge hit: Lend me a Tenor. Again, I was fortunate to be involved in this production. And again it was a comedy, a farce to be exact, with lots of slamming doors and mistaken identity. However, it was the success of another show—The Melville Boys—where the demand for tickets was simply overwhelming. Even with additional performances there were many people unable to get tickets.

The message was obvious: the theatre needed more space. So in the spring of 1997 a major expansion took place. Walls were knocked out and the space redesigned to include more office space and a doubling of the seating capacity to 228.

By this time Hans Saefkow had joined the theatre. This multi-talented man from Smithers could do it all: carpentry, lights, props—everything. A graduate from The Ontario College of Art, he was the perfect artistic partner to Price. Ted and Hans would collaborate on set design, then Hans would build them and paint the scenes. The result was magic for the audiences, who marveled at each stunning creation. For me, it was the sturdiness and functionality of each set that I really appreciated. Whether it was a spiral staircase or slam-proof doors, everything was ready to climb on or slam the first day of rehearsals.

This commitment to excellence means Theatre North West is a year-round operation. In early May, after the last show of the season, Price and Laughlin change gears and prepare for trips to Toronto, Edmonton, Calgary and Vancouver to meet and audition hundreds of actors. When they return, offers are made to actors, the shows are cast, and it’s time to start another season.

The hard work and dedication has paid off. Subscription numbers have climbed by seven percent each year and have passed the 3500 mark so far this season. And, as a regional theatre, they are encouraged that 25 percent of the subscribers are from places like McBride, Mackenzie, and Smithers. In fact, the theatre sells more tickets per capita than any professional theatre in Canada.

I may have chosen another city besides Prince George to live in for the past 12 years, but I have done more shows for Theatre North West than for any other theatre. And there is a certain pride and thrill in witnessing an idea for a professional theatre become a thriving reality—a theatre which has employed not only me, but hundreds of actors, designers, administrative and technical people, and which has added much to the cultural life of this area.

Editor’s note: Here’s a little something from Anon:

HOW MANY THEATER PEOPLE DOES IT TAKE TO SCREW IN A LIGHTBULB?

Q: How many actors does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: None. Complain to the director at notes.

Q: How many directors does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: None: Give a note to the stage manager to fix it.

Q: How many stage mangers does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: None. Pull the technical director off a set installation to deal with it.

Q: How many technical directors does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: None. Call the master electrician at home to fix it.

Q: How many master electricians does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: We don’t do bulbs, only halogen lamps. It’s a props problem.

Q: How many props masters does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: Light bulb? When did they even get a lamp?

Q: How many theatre critics does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: All of them – one to be highly critical of the design elements, one to express contempt for the glow of the lamp, one to lambaste the interpretation of wattage used, one to critique the performance of the bulb itself, one to recall superb light bulbs of past seasons and lament how this one fails to measure up, and all to join in the refrain, reflecting on how they could build a better light bulb in their sleep.

Q: How many theatre students does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: Er, what’s the deadline? I may need an extension.

Q: How many audience members does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: Three. One to do it, one child to cry and another to say, “ROSE, HE’S CHANGING THE LIGHT BULB!”

Q: How many interns does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: It doesn’t matter, because you’ll have to do it over again anyway.

Q: How many directors does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: Four…no make that three…on second thought, four…well, better make it five just to be safe.

Q: How many producers does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: None. Why do we need another light bulb?

Q: How many stage managers does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A1: I DON’T CARE—JUST DO IT!

A2: None. Where’s IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees)?

A3: It’s on my list…it’s on my list…

Q: How many IATSE guys does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A1: One, once he puts down the donut and coffee.

A2: 25 and a minimum of four hours. You got a @!%#& problem with that?

Q: How many electricians does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: LAMP! It’s called a LAMP, you idiot!

Q: How many lighting designers does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: None. Where’s my assistant?

Q: How many actors does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A1: None. “Doesn’t the stage manager do that?”

A2: None. They can never find their light.