The Dundas collection

They were given up for God during the tumult of colonialism and trade on BC’s North Coast, but now pieces from a prized collection held overseas for close to 150 years are finally returning home.

“They stopped our people from making them,” says James Bryant of the Allied Tsimshian Tribes, based in Lax Kw’alaams (Port Simpson). He is referring to the carved masks, shaman’s rattles, feast dishes and chief’s hats used regularly in the winter ceremonies of his ancestors. Although the potlatch was not banned until 1884, pieces like those recently purchased by Canadian philanthropists and museums from the collection of a Scottish chaplain—who traveled BC’s west coast in the mid-19th century—were considered “Indian devilry” by the missionaries of the day.In March, the Tsimshian will have the first chance at seeing some of the famous Dundas collection back on the west coast. A new exhibit featuring several of the finest pieces will open March 1, 2007 at the Museum of Northern BC in Prince Rupert. From there the exhibit will travel to the Royal BC Museum in Victoria.

Bryant is pleased these masterworks detailing his people’s ancient tribal lineages will once again be in his territory, but the circumstance of their disappearance continue to haunt him.

Community of the converted

In 1863, the young Reverend Robert J. Dundas made a brief stop at the village of Metlakatla, where, as he wrote in his journal, he spent an enthusiastic morning examining “Indian curiosities.”

Metlakatla, on the Tsimpsean Peninsula west of present-day Prince Rupert, was once the winter gathering place of the nine Tsimshian tribes, but when Dundas arrived on that October morning it was a fledgling community of those newly converted to the word of God.

The conversions, and the community itself, were the brainchild of one of the most famous and controversial missionaries on the coast. William Duncan was a lay Anglican minister who arrived at the Hudson’s Bay post of Fort Simpson at the height of the fur trade. After several years of struggling in the debauched environs of the trading post, Duncan and 350 now-Christian souls made their way south to the unpopulated beaches of Metlakatla.

Among other puritanical demands, Duncan insisted that his converts give up the material trappings of their formerly pagan ways. When the great chief and medicine man Paul Legaic—a man who had once tried to kill Duncan for trying to stop the secret winter ceremonies—joined the flock, it was one of his triumphs.

When Dundas—an enthusiastic collector who sought the “implements of the medicine men”—arrived, Legaic’s recent conversion was a coup. The Reverend sailed away with several of the shaman’s most prized tools.

Act of Providence

Dundas was by no means alone in his hobby. Bryant says there are at least 26,000 Tsimshian cultural treasures in museums around the world. The circumstances surrounding the collection of these artifacts is mired in the details of that devastating time in history. When Duncan and the others moved to Metlakatla, smallpox was ravaging the coast. That year 500 died of the disease at the Hudson Bay trading post, whereas only five were lost in Metlakatla. Duncan had no qualms about suggesting this was an act of providence.

Today, “an act of providence” would be one way to describe how the artifacts will make their way home.

After his journey on the north coast, Dundas took his booty back to Scotland. In the years that followed, the collection languished in the family home.

Much later, Dundas’s great-grandson, the 77-year-old Londoner Simon Carey—who once stopped his grandmother from throwing what was then considered a strange and musty box of old clubs, rattles and bowls into the trash—knew the value of the collection and had offered the pieces for sale before. Although Canadian institutions had shown interest, none could afford Carey’s asking price.

Finally, in October 2006, the Dundas Collection—one of the last well-documented 19th-century Northwest Coast field collections in private hands—was auctioned at Sotheby’s in New York. Sotheby’s estimated the group of artifacts would bring in $3.4 million, but after the gavel swung on the final lot, enthusiastic collectors had bid more than $7 million, a Sotheby’s record for native North American art.

“The artifacts were taken for nothing by the missionaries. Now the missionaries’ grandchildren are going to become millionaires out of what happened in the 1800s,” says Bryant.

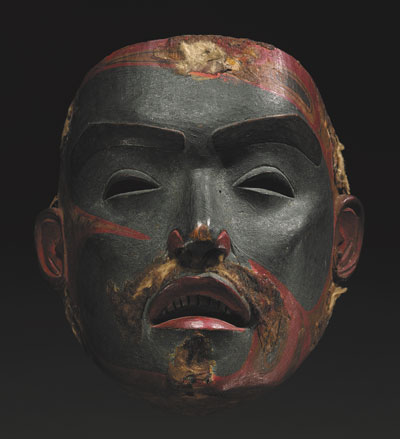

Art dealer Donald Ellis, who bid on items for several Canadian institutions and two Canadian philanthropists, sees things from a different perspective. He says history will show that the prices paid at the Sotheby’s auction were a bargain. According to Ellis, who successfully purchased 28 of the 57 lots for a total cost of $5.8 million (US), the record-breaking $1.8 million paid for a prized shaman’s mask is a pittance in the world of tribal and ancient art. “It was almost a giveaway,” he says.

A 19th century African mask sold in Paris for $7 million, and pre-Columbian artifacts fetch prices in the tens of millions, he continues. In the contemporary art world, a Gustav Klimt painting can sell for as much as $135 million. Even what Ellis describes as a mediocre Lawren Harris piece sold for $1.6 million at auction.

Shopping list

Before the Sotheby’s sale, Ellis tried to round up funds from federal, provincial and private sources to help his two museum clients keep the collection in Canada, but by the eve of the auction he’d not been very successful. The Canadian Museum of Civilization had a $100,000 US budget and the Royal BC Museum, in concert with the Museum of Northern BC in Prince Rupert, had another $100,000—plus a shopping list of priorities from the Allied Tsimshian Tribes.

Frustrated by the lack of government commitment, Ellis challenged Canadians in a Globe and Mail article the day before the sale, to step up to the plate and make a difference for the country’s cultural heritage.

That night, the last-minute phone call came. Ellis arrived at the auction with a budget exceeding $5 million. Ontario’s David Thomson and his cousin Sherry Brydson of Victoria, son and niece respectively of the late Canadian philanthropist, newspaper magnate and art collector Kenneth Thomson, bankrolled the record-breaking purchases. Nineteen pieces, including the most valuable—the shaman’s mask, a carved antler club for $940,000 and a frog clan hat for $660,000—were purchased for the Thomson cousins.

The Museum of Civilization spent their budget on five small pieces, but the Museum of Northern BC, in partnership with the Royal BC Museum—after all their planning with the Tsimshian—only acquired a carved wooden spoon for $22,800. In the end, the cost of the pieces they wanted were too far out of range and most of their funds were never spent.

But in a watershed moment for Canadian cultural heritage, Ellis has seen to it that the pieces purchased by Canadians will be brought together in an exhibit, which will travel first to Prince Rupert.

For Bryant, seeing the pieces will help unravel the tribal lineages of his people, knowledge that was further scattered when Duncan moved his Christian community from BC to Alaska after he broke from the Anglican Church. Bryant and other elders will spend some time alone with the artifacts before they are put on display.

But he is still disturbed by the high prices being paid for his people’s things and blames the Canadian government for not setting things right by bringing these objects home.

He relates the inability of Canadian governments to protect his ancestors’ artifacts by at least bringing them all back within the country’s borders as another failure to properly compensate First Nations people for the wrongs of the past: residential schools, the banning of the potlatch, and the loss of traditional Tsimshian lands,

“Two levels of government can’t even pay us for the land they took for nothing. Now they are putting a big value on our artifacts,” he says.