A slippery slope:

The difference between what’s planned and what actually happens—when it comes to oil and gas development—brought Rosemary Ahtuangaruak from the North Slope of Alaska to BC’s North Coast shores.

Ahtuangaruak is the mayor of a tiny community called Nuiqsut, population 523. The Inupiat community is out on the Barrens just 160 kilometres west of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, but it’s surrounded by several oil and gas developments, on land and sea, including ConocoPhilips’ Alpine Oil, which is within seven kilometers of the village.

While speaking to locals on Haida Gwaii in October 2007, Ahtuangaruak said her community was one of the first to negotiate with industry on oil and gas development on tribal lands, but a decade later many of her people feel they were gravely misled.

When the community agreed to the Alpine development they were told it would impact just 14 acres of tribal land. After 10 years, she says, the project has spread incrementally across 500 acres and the community has found out it has no legal recourse.

Despite the oil industry’s claims that Alaskan arctic drilling is the least intrusive ever undertaken, Ahtuangaruak says lack of enforcement of any of the negotiated terms between her community and industry have left her people facing health impacts and dealing with major impacts on fish and wildlife, which in turn affects their traditional way of life.

Since 1986, when she first started working in the health field, the number of people needing medical help to breathe has risen dramatically.

Nuiqsut is 15 metres above sea level on the tundra, and Ahtuangaruak says she can see the natural gas flares from the clinic. The nights when they light up the sky are the same nights she, and other medical staff, can’t leave the clinic for helping people with inhalers, nebulizers, steroids and antibiotics.

Two hundred decibel booms, the equivalent of a jet engine starting up, have diverted the bowhead whales off shore. They used to be caught within five kilometers of shore, but now whales are more than 30 kilometres out, making hunting even more dangerous.

The community negotiated a limit on flight activity in the area during June and July, when people traditionally hunt caribou. Planes are required to bring in resources, workers, and more—but the 20 flights agreed to during negotiations has turned into 1,900 flights during the summer hunting months.

The added noise has had a negative impact on the caribou. Before the Alpine oil field got underway, 97 out of 105 households in Nuiqsut successfully hunted caribou. After the development only three households managed to hang an animal.

When, not if

So what does this have to do with British Columbia’s coastal communities?

Margot McMillan, staff counsel at West Coast Environmental Law brought Ahtuangaruak to Haida Gwaii and Prince Rupert so locals could talk directly with someone who has lived with the impacts of oil and gas development.

She says that while states like California, Oregon, and Washington support a 25-year US ban on offshore drilling, the BC coast is no longer safe because the Canadian government is trying to deny the existence of a 34-year year-old moratorium on tanker traffic off British Columbia’s north coast.

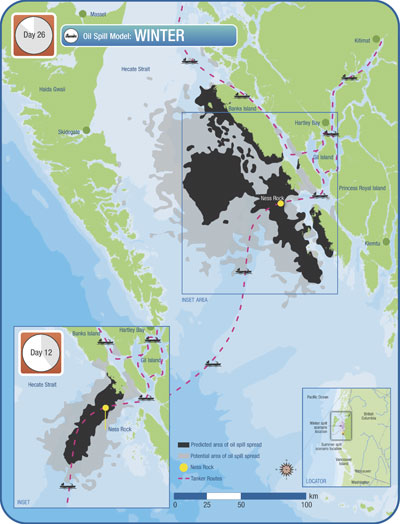

The moratorium, put in place in 1972 due to widespread concern over oil spills in the delicate coastal ecosystem, covers Dixon Entrance, Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound. It was followed by a similar moratorium on coastal oil and gas development.

In the 1980s, both the federal and provincial governments considered lifting these and other moratoria on coastal oil and gas activities in BC, but then in 1989 the Exxon Valdez ran aground.

The day 11 million gallons of unrefined crude oil spewed into Prince William Sound on Alaska’s south coast is known as “the day the water died” to local aboriginal people. Even Environment Canada has done studies that say it’s not a matter of if, but when another catastrophic oil spill will occur.

Government in denial

Meanwhile, oil and gas activity is far from the BC coast as the tar sands of Alberta is fueling the Conservative government’s new strategy when it comes to the moratorium.

Natural Resources Minister Gary Lunn has told reporters and environmentalists the moratorium doesn’t exist. “There is only one tanker routing measure in place off the west coast of BC…The Tanker Exclusion Zone, in place since 1985, is a voluntarily-adopted measure…” he writes in a letter addressed to the Pembina Institute, another group working to uphold the moratorium.

McMillan calls Lunn’s response a sleight of hand because of the strange fact that no one has found an order in council or a piece of paper documenting that it exists.

“Clearly the intent was there and the government has operated on that intent for the last 30 years,” says McMillan who, along with others, has prepared a five-page list of parliamentary and other sources referring to the moratorium.

According to the Dogwood Initiative, a Victoria-based group that supports communities’ rights to make their own land-use decisions, 14 tankers loaded with condensate—a chemical byproduct of natural gas needed to dilute crude oil from the Alberta oilsands—have already taken advantage of the confusion.

The port of call was the community of Kitimat, far up the 90-kilometre-long Douglas Channel. And this community could become the terminus for more than just condensate; several tanker and pipeline projects designed to help expand the extraction and transport of crude oil from Alberta to Asia and the United States are proposed for the region.

Petroleum to the rescue?

Some believe the oil and gas pipeline potential could be the economic boost the town needs. Reliant on Alcan as a major employer during the last 50 years, the company’s workforce topped out at 2,700 in the 1970s and has been on the decline ever since. Proposed upgrades to the plant may see another 500 jobs lost in the near future. In the last census, Kitimat had the largest percentage population drop in Canada, falling nearly 13 percent to below 9,000 people from 10,300 in 2001.

Gerald Amos, chair of the Na Na Kila Institute, a conservation group based in the Haisla Village of Kitamaat, and former chief councilor of the Kitamaat Band Council, says that despite the potential economic gain, the community must think long and hard about this type of project before deciding it’s okay.

He was sorry that Ahtuangaruak didn’t make it to Kitamaat (she was hindered by bad weather), because he doesn’t think villagers have heard enough about the downside to the idea of Kitamaat becoming an energy corridor for oil and gas.

The Chamber of Commerce and the present band council may be in favour of the development, he says, but there is a bigger picture. “Decisions made in the tar sands will impact us in Kitamaat,” he says. And in the same vein, “decisions made in Kitamaat will have an impact on Hartley Bay, Haida Gwaii and other coastal communities.”

He remembers the time before even Alcan came to Kitamaat’s shores, and he’s witnessed the change. “Some say it’s progress, but I’m not sure,” he says. “I believe we don’t have a good grasp on the cumulative impacts of these industries.”

His biggest concern is climate change. According to the Dogwood Initiative, “every single barrel of oil produced in the tar sands creates 80 kg of carbon emissions—more than the average car produces driving from Vancouver to Whistler and back.” Tar sands production currently tops 1.1 million barrels a day.

Amos isn’t sure he wants to be a part of that. But mostly he wants his community to weigh the pros and cons of this type of development before leaping into the fray.

For more information:

www.dogwoodinitiative.org

www.nanakila.ca

www.pembina.ca