Oliver

Jen Brubacher is the winner of the Terrace Writers Guild Fictional Writing Award. You can read Jen’s blog at jbrubacher.blogspot.com/

She ran so that her only sensation was in the hard slap of her feet against the tarmac and the burnt pain of her lungs in her chest. One reasonable part of her mind considered the soft wet grass beside the pathway, but the rest of her was so intent on reaching the house that she couldn’t steer herself away. Tall shadows of trees rose before and fell behind her so quickly they didn’t have the chance to be terrifying. The sky was a black absence a million miles above. But the white house grew and grew as she ran, and its big square windows held light that beckoned her even more quickly as they began to burn through the night. Ada ran, and ran, and when she came to the tall black door and stopped, her legs still felt in motion, the muscles’ memories stronger than truth.

The door open the smallest crack and a short figure blocked some of the light from reaching her face.

“Did you get it?” Oliver asked.

“Yes,” Ada said, and the breath that it took was a last slash through her lungs. She held out a hand and he held out his. She dropped it into his palm.

He closed the door.

§

Oliver’s brother Stefan said that Lamott School was reserved for “the lonely, the important, and the dying.” He had bellowed it over the lake while Ada tried to ignore him and read her textbooks beside Oliver. She heard bitterness in Stefan’s words. There was no reason to be bitter about Lamott School, especially for Stefan. He was only there because of his brother. He could have gone home. This made him unique.

Before Lamott, Ada lived with a young couple in the city and learned about trades: cleaning, ironing, and mending. Lamott gave her science and literature and languages. It was like she’d only had dry bread and now she was introduced to butter. She couldn’t see the use of the things, but it was a treat to learn them.

And then there was Oliver. With him, she was neither the smallest nor the most delicate. Making him smile was worth a gold star. She held open his textbooks and sat amazed by his brilliance. He had already learned everything, but the school let him prove it.

Each square stone building sat in a wreath of short hedges, except the white house where Oliver lived with his brother and the other kids who were neither lonely nor important. The grounds were smooth green fields. Nature had her say with the lake; it was shaped like a snake and wound lazily beside the square buildings, in defiance of their order.

§

In the dormitory on the morning after her run, the teachers were stuck into a cluster in the entranceway. Ada walked slowly past them, trying to hear what they were saying, but caught only words separated from their sentences and their meaning.

“He…”

“…mouth…”

“…never…”

“…future.”

They saw her listening and glared as one unit until she hurried on.

Class was no better. Mrs. Sauber was distracted and set them all to write neat handwritten lines while she paced by the window. The sky was cloudy and the cool air wouldn’t dry out the grass, so everything looked damp. The trees that lined the path to the white house sat as mute sentries. Ada tried to look where Mrs. Sauber was watching but the teacher’s eyes were on the ground, the sky, or the windowpane, and flickered uncertainly. The rest of the students caught her anxious mood and started to fidget.

“Work!” Mrs. Sauber yelled, and they froze and stared at their pages.

Ada looked at her teacher’s pale face and thin, lined hands and was reminded of Oliver. She looked at the dark wood walls and thought of the carved black door where she’d last seen him. She remembered his small steady hand.

“So young,” Mrs. Sauber muttered. She crossed her arms and shivered. Ada looked outside at the white house.

§

Oliver’s brother was nothing like Oliver. Stefan was dark-haired and strong and sat close to Ada while their teachers stood rigid, as if they thought statues would be reassuring.

“Of course, we won’t expect you to finish your exams, given the circumstances,” Mr. Gott said with a comforting grimace. There was a general sigh among the students, as if this was good news that they nevertheless couldn’t receive happily, given the circumstances. Stefan leaned against the hard concrete wall of the gymnasium and the wooden bench beneath them creaked. Ada shivered away from him.

“I thought it would help,” she whispered, just for him.

“It did,” said Stefan loudly. The teachers looked at him and he looked back evenly. Each chose a different moment to look away. No one spoke against him.

“I’m sorry,” whispered Ada.

Stefan leaned back towards her until his arm touched her shoulder in one warm, solid gesture. He felt nothing like Oliver.

§

Oliver’s hands were like a bird’s bones in cotton cloth. His head was large on his neck and he walked with a slow grace that seemed always on the verge of disaster. Nothing about him made the correct angle with itself. Ada was tall and solid next to Oliver. She walked a few feet away and was his wall if he needed to catch himself.

The teachers were used to broken children and played no favourites. Oliver’s papers came back as marked with red pen as anyone’s, except that his grades were always good. Ada had learned not to question his logic. He might know nothing about the dry bread trades, but his butter-knowledge was perfect.

“It’s good that you see education as food,” he told Ada.

“Does that hurt?” she asked him, looking at his ankle bent backwards against the hardwood, twisted where his leg had settled when he sat.

“Oh,” he said. Stefan reached over and roughly pulled his brother’s leg up, setting it back properly. The knee of Oliver’s trousers stayed wrinkled into Stefan’s handprint.

§

The chemistry teacher had the most to say. His eyes were the reddest. “He was a very diligent student with varied skills,” he boomed, and the sound hunched the students’ shoulders. “If I had known…if I had believed…” His voice failed and the mathematics teacher led him away from the casket before he could collapse. No one wanted to hear the details, though they’d all wanted to hear the details, and they all had the image in their minds. Oliver lying on the floor of his dormitory in the white house. Oliver with his arms stretched over his head. Oliver with a spray of white foam from his mouth over the polished wood floor, his uniform baggy on his light frame, deflated with his illness. Some of the students saw his eyes open. Ada saw them closed.

“But how did he get it? How did he get the poison?” The school was astonished as a whole. They were accustomed to death, but that was passive. This was an action against life.

“I’m sorry,” Ada whispered to Stefan, and he pressed her hand between his own and wouldn’t look at her.

§

Oliver’s parents visited Lamott School near the first of every month. The day of the week was irrelevant. They’d find their son and put him into a wooden chair on wheels and roll him out to the lake with Stefan walking behind. This was one of the few moments Ada was asked to stay away from Oliver, and she hated it. She believed that Oliver hated the wooden chair and its small hissing wheels.

“He was such a gifted boy,” the teachers said, and “He will be so very missed.” Ada had heard the rise and fall of Oliver’s father’s demands for an explanation through the door of the office, and the way it gradually made way for Oliver’s mother’s quiet sobs. When the office door opened they had looked down at Ada and then over to Stefan, who leaned against the wall behind her. They all just looked for a long time, and then Stefan glanced down to the ground.

“We know you were his friend,” Oliver’s father said to Ada. “Thank you.”

§

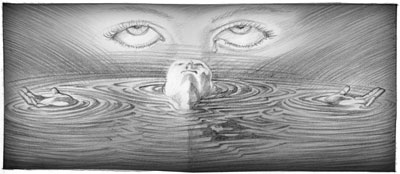

Ada dreamed about the lake. She sat under a tree and watched while Stefan held his hand in the water. It was night, and the water was black, Stefan visible in the vivid one-tone moonlight. His strong back was bent over in a beautiful curve and she couldn’t see his face. The water was still, but punctuated by a steady drip just beneath his face.

“Get your hand from the water,” she said. “It’s burning you.”

He leaned back and his hand rose slowly out of the lake, making a circle ripple out to the shore. She wanted to run over and pull on his arm, it was moving so slowly, like it was connected to a great weight. She didn’t understand it. Stefan was the healthy one.

“What’s wrong with you?” she said.

As his hand came up over the water she saw his brother Oliver’s head connected to it, stuck as if they were one body. As she watched, Oliver’s eyes rolled and the weight suddenly shifted so Stefan was pulled under, his curved back a delicate pivot as his body disappeared into the black.

She woke up.

§

It took Ada the whole summer to stop being sorry. Then she was angry, and then she was sad. Stefan spent all of it being nothing. When Ada stopped apologizing she yelled at him, and then she screamed at him, and then she wouldn’t speak to him. He nodded, and he shook his head, and he let her go. When she retreated to her room and lay on her bed, sobbing and staring with sore eyes at the white walls, Stefan sat on the other side of her door and read a book so she could hear the pages turning.

“You’re nothing like him,” she said quietly. He heard, and left.

Her guardians decided that she should change schools to erase the memories that had paled her face and made her eyes dark. She didn’t argue. She thought vaguely that it was punishment, and that she could finally be free of the guilt. She moved her things from Lamott in a small blue sack a teacher had given her, and didn’t look towards the white house until it was too late and the trees had obscured the view. She treated the memories this same way, not touching each until they seemed distinctly faded. This is when she became someone new: a different Ada whose life was not punctuated by such horrors.

§

She remembered Oliver as the fine frame around the photograph of Lamott School, and her time with him as golden. Her studies after he was gone were in his honour.

She remembered Stefan as a tall, dark-haired boy who lost a brother and disappeared into himself. Eventually, she began to pity him, and as a young woman she imagined that he’d have been a friend, if only circumstances had been different.