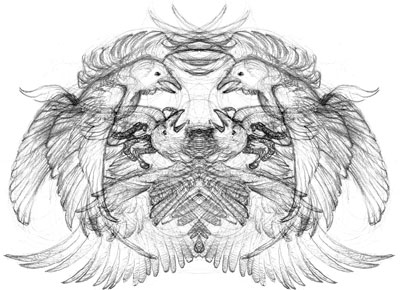

Raven

To the Haida, the raven was the first creature, the one who made man. To the Haisla, the raven was the magician—the trickster. To the old-world European, he was a black bird, a dire bird: an ill omen.

But you should watch this flyer when the wild, wet, west wind comes gusting off the water and over the land. He comes then to teach his offspring the delights of the wind. The robin uses flight as a tool—to get from point A to food at point B. The grouse uses flight to escape the fox and the sable. The raven revels in flight; he practices joy in flight and teaches his young the glories of it.

When the grey gusts come up off the water he sits, there on the top of the dry cedar snag, awaiting the right gust. When it comes he opens his wings and rises—straight up, without the slightest movement of his wings. He rises up and up, riding the wind higher and higher. When the gust slackens, he cups his wings and drops like a stone. Down and down, the wind ripping at his feathers; down farther, wings set for the fall.

It seems impossible that he could recover from this stoop, but at the last instant he catches the wind under his wings, spreads them strong—and bounds back into the sky. Up and up, higher and higher. At the top of the pinnacle, he catches the gust again, and rides and soars, effortless and serene.

His young join in, by twos and threes—following, flying, trying to catch the elders. They scorn the harshness of the day. The wind was made for flight; the stronger it blows, the better. They fly not to find food or escape, but for joy, for thrills, for excitement, just as the otter plays and revels in the water.

The south wind dies and the crows—those little black scalawags—leave the winter skies to the ravens. The snow comes, and the fierce north wind blows its bitter breath into the raven’s eyes, and the raven soars and sails and loves it all. He lives through the bright, brittle winter, using his intelligence and his wonderful eyesight. He rides on the wind, and far, far below he spies a spot of blood on the snow, shining like a beacon. Down he goes in a great circle, spiraling, the circles getting smaller and smaller. Near the ground he is pivoting in just a wing span. He touches the ground and springs back into the sky, beating, beating, until he can catch the wind again. This is the signal, this great spiral repeated until every raven for miles comes to the feast.

When spring comes again, as he knew it would—great glorious spring—he does his dance of love. Catching the tiniest puff of wind, he goes up and up while his love, perched in the dry snag, watches, impassionate. At the zenith of his ascent, he turns over, inverted, looking like a basket of broken bones. He falls then, like a stone but with direction, coming as close to his intended as he dares. He catches the wind again and rises once more, up into the sky.

The thrill of this flight knows few bounds, but its joy is trebled when shared—when his love joins the ballet in the sky. They fly as one, plunging down, then bounding to the sky—when they reach the zenith one goes inverted and they touch their feet, thrilled just to fly together.

They nest is in a high lonesome tree, sharing and caring for their young, a task that leaves little time for other things, fun things, over the long summer.

But when the fall winds, the wet winds, come off the water and blow across the lands, the new family comes forth to play on the wild, west wind. They rise on the gusts until it seems the excitement will never end. They sail and they soar; then, cupping their wings, they fall, playing “catch me” with mother and father. At the last moment mother or father go inverted to touch the feet of their beloved children.

The old Europeans were wrong. This is not a bird of ill omen; this is a bird of adventure, of cunning, of intelligence. Creatures without intelligence do not play on the wind or on the water.

This is the Haida bird, the first creature. This is the Haisla bird, the magician…the trickster.

This is the Raven.