Fifty years of Haida weaving:

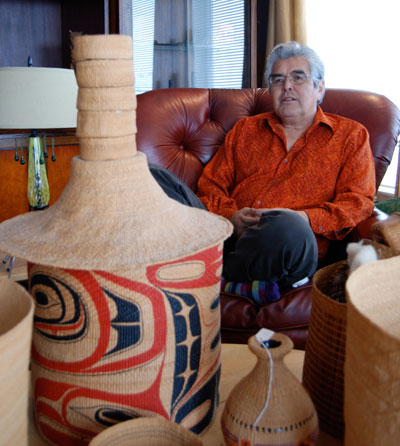

World-renowned Haida artist Robert Davidson remembers when a weaving was considered a curio and not a piece of art.

It was the early 1960s, and he was attracted to a conical spruce-root hat made by Emily Thompson, an elderly woman in the village of Massett where he grew up. He knew nothing about the techniques involved—the elegant design twisted between the warp and weft, or the long process of digging, roasting and peeling the moist roots—but he admired the beauty of the piece and asked the price. When he heard it was $25, he couldn’t believe his ears. That was far too little, he thought, so he gave her $40 instead.

Davidson still shakes his head at how inexpensive these intricately twined strands were. Not only were hats and baskets, which can take upwards of a week to create, selling for ridiculously low prices less than 50 years ago, there were very few weavers working at the time. The ice cream pail had replaced the woven berry-picking basket as an essential household item, and not many young people were taking time to learn from their elders and continue the practice.

A collection begins

He didn’t intend to become a collector when he made that first purchase, but over the years, Davidson has bought so many pieces and has remained so impressed by the unbroken thread of knowledge that has passed between grandmother and granddaughter, aunty and niece, master and apprentice, that he wants to encourage more people to take an interest in the art form.

“You can’t fake weaving,” he says, acknowledging the skill and tenacity of women like his cousin Isabel Rorick, who learned the intricate patterns and processes of spruce root weaving from her naanii (grandmother). Other Haida artists, he says, can either paint over their mistakes, carve them off, or ignore them. “But in weaving, if there is one twine that is not right, your eye goes right to it.”

That’s why his 90-piece collection—ranging from the first hat he bought, to a collection of jewel-like miniature baskets, to a bevy of wearable art like the striking black-and-white geometric forms of a Raven’s Tail wool robe—is showing at the Haida Gwaii Museum in Skidegate this summer.

The show features a continuum of pieces by historic master weavers like Selina Peratrovich and Florence Davidson, contemporary greats like Primrose Adams and Delores Churchill, along with mid-career and emerging weavers working today.

“We’re really lucky. If you go to other nations on the coast, they don’t have the same number of weavers that we do here,” says the show’s curator, Kwiaahwah Jones.

Haida weaving—whether with spruce roots, cedar bark, ferns, grasses or other fibres like wool—shows our deep connection to the land, she says.

Important process

Collectors and other aficionados may appreciate the finished work, but to weavers the process is one of the most important aspects of the art: from the respect paid to the forest while harvesting and preparing cedar bark and spruce roots to the meditative interplay between the warp and weft in the various designs.

“We are the land and the land is us,” says April Churchill (daughter of Delores, sister of Evelyn and granddaughter of Selina). “This knowledge is ingrained in the very fibres of our selves by our grandfathers and grandmothers.”

Churchill, who learned to weave from her grandmother, says there is ceremony around gathering cedar bark. Looking for the right tree—about 60 cm around, straight, and with no branches on one side—involves a lot of walking in the forest. When a suitable specimen is found, the weaver must look around to see that the other trees in the area are healthy. Then she waits.

“If you stand quietly, you can actually feel the trees that want you. You can feel the ones that have a gift for you. When you discover which those trees are, you go over and there is a small thank-you ceremony that we do.

“Nobody told us this is how you do it, we just watched our naanii and mother do it as we were growing up. It’s the same with my children.”

The right trees have become harder and harder to find with all the logging that has taken place over the last 50 years on Haida Gwaii, but Churchill remains true to the process. Once, a logging company offered to let weavers come in and strip the bark off cedars that were going to be felled and barged off the islands. Normally weavers take a strip only six cm across so the tree can heal, she says. The loggers were offering the bark from all the way around the trunk. In the end, though, she and the others couldn’t bring themselves to do it.

She also remembers being young and too impatient to follow her naanii’s teaching—just rushing in, grabbing bark and heading home to weave. “The truth was, not anything that I worked on, nothing that I did with that bark, worked out at all, so she was exactly right.”

Wooly work

Besides cedar bark and spruce roots, the Haida also use wool for their weavings. One of Davidson’s earliest collected pieces was a dancing apron, woven in the Chilkat style by Cheryl Samuel, an internationally renowned weaver and teacher. It was she who revived the more ancient practice of the Raven’s Tail blanket.

At one time the wool for these blankets (spun over a core of cedar bark) was harvested from mountain goats. Since these animals do not live on Haida Gwaii, the material was acquired through trade with mainland tribes. Known in Haida as Naaxiin (Fringe around the Body), the robes feature a two-dimensional design that is so complex it can take one year to complete a full robe.

Although the garments still take as much time to create as they did in the old days, gathering wool is a different matter today. Most weavers eschew mountain goat wool and stick with merino now.

“My harvesting practices are really difficult: I phone this very nice wool shop in Ireland and I order,” said Lisa Hageman of Massett, at a weaving symposium held at the Haida Heritage Centre at Kaay Llnagaay last August. One of her Raven’s Tail robes, a white blanket with black geometric pattern, adorns a model as part of a permanent display at the Haida Gwaii Museum. These blankets are described by sailors on some of the first ships that came to the Pacific Northwest in the late 1700s, but are rarely found in museums—only 11 historic pieces exist in collections around the world.

Weavers like Hageman and Evelyn Vanderhoop, also of Massett, and with whom she apprentices, are teaching and bringing the style, known as Qwiigaal Gyaat (Sky Blanket), back into practice today.

Big baskets

Another piece that inspired Davidson was a 75-cm diameter cooking basket that he saw at an art dealer’s in Seattle. The 1880s piece was folded (the Haida used to store them this way to save space, especially when travelling by canoe) and when unfurled the height was the same as its width.

He challenged his Auntie (Primrose) and his cousin, Isabel, to make the biggest baskets they could and their 30-cm diameter efforts will be in the show, with his promised design painted onto the weave.

Davidson and his family have made it their mission to acknowledge the many Haida weavers, and they held a series of potlatches to honour them in the spring of 2008. He says reconnecting with the standards set by the masters of the past should be the goal of all Haida artists.

It’s true, Davidson says, that some of the pieces in his collection are treated like art; they were made to be admired and now decorate the mantles and shelves of his White Rock home. But for him the greatest importance of woven art remains in the functional realm. He and his family have danced all the clothing—the hats, robes, tunics, aprons, leggings, headbands and more—at various potlatches and feasts over the last two decades.

Twenty years ago, only a handful of individuals wore cedar hats at potlatches, feasts and other public events, he says. Today, at every event on Haida Gwaii—and even at events in cities like Vancouver or Seattle—almost every attendee is adorned with some type of woven apparel. Fifty Years of Haida Weaving: The Robert Davidson Collection, at the Haida Gwaii Museum July 17 to August 28, 2009, honours this shift.