Sternwheelers on the Skeena

The mighty Skeena River flows past the historic community of Hazelton and drops a remarkable 800 feet (255 metres) over 300 km to join the ocean at Prince Rupert. Despite the river’s sharp curves, rocky canyons and temperamental water levels, it was once a major transportation route for First Nations, explorers and early settlers.

In the early years of white exploration and settlement, impressive canoe brigades moved up and down the Skeena, bringing supplies from the Hudson Bay post at coastal Port Simpson to the inland post at Hazelton. It took about one week for four or five strong First Nations men in a fully loaded canoe to battle the current upriver to Hazelton. They used a combination of poles, oars and ropes to pull and push their way upstream. These experienced river-men would unload the Hudson Bay Company supplies, then load the canoes with large bundles of furs and the occasional passenger—and return to Port Essington in just over one day.

In 1864 and 1866 two sternwheelers for the Collins Overland Telegraph Company attempted to go up the Skeena, but both underestimated the strong current and moody disposition of the water. Neither sternwheeler succeeded in churning past the Kitsumkalum River, in the vicinity of today’s Terrace.

For many years the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) relied on canoes and river-wise First Nations men to bring freight upriver. In 1890 the Company took a chance and built the Caledonia—the first riverboat for the Skeena River. The mighty Skeena discouraged the boat’s first two skippers, but the third, J.H. Bonser, was up for the challenge.

It was Captain Bonser who named many of the rougher spots along the Skeena, like the Hornet’s Nest, the Whirly Gig, and Devil’s Elbow. For years the Caledonia was the only sternwheeler on the river. Bonser learned where landlines had to be secured to large ring-bolts on rocky islands, where on the riverbank to keep a supply of wood and, most importantly, exactly how many inches of water the paddles required to make it over submerged rocks.

Sternwheeler rivalry

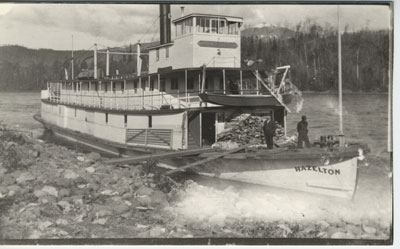

Competition for the Caledonia was inevitable, though, and arrived in 1901 with the construction and launch of the sternwheeler Hazelton. Mr. Robert Cunningham had the Hazelton built to ensure that supplies for his store in the village of Hazelton would no longer be subject to the whims of a Hudson Bay Company boat.

Cunningham guaranteed a rivalry by not only asking the HBC’s Bonser to help design the new paddleboat, but also managed to convince him to quit the HBC to pilot the Hazelton.

In response to Cunningham’s bold move, and the loss of their former Captain Bonser, the HBC built yet another sternwheeler, the Mount Royal. Constructed of Douglas fir and eastern oak, the new boat had luxurious quarters built to pamper passengers. However, during her launch in April 1902, the lavish Mount Royal became tangled in her ropes, and several days of struggle followed before the vessel was successfully in the water. A bad launch is considered an ill omen, and in this case it was one that came to be fulfilled.

The HBC’s Mount Royal, under its new Captain Johnson, and the Hazelton, with veteran Captain Bonser, quickly developed an intense rivalry. The paddleboats stole each other’s woodpiles and dangerously crowded each other in the strong river currents.

Passengers joined the chaos, jeering at the other boat and cheering on their captains. The paddleboats sought to make the fastest round-trip from Port Essington to Hazelton and back; beating the other’s time was paramount. Passengers and riverside settlers encouraged the competition by wagering on record-breaking times, first spring run upriver, or last boat before winter.

The first boat of the season to reach Hazelton was celebrated, and in the spring of 1904 Bonser on the Hazelton and Captain Johnson on the Mount Royal vied for the honour.

The Hazelton left the coast first, but stopped for wood at Hardscrabble Rapids, near present-day Usk. While there, they saw the Mount Royal gaining on them. Wood and men were rushed aboard and the Hazelton pulled out just as the Mount Royal approached. Much to the delight of the passengers, the two sternwheelers raced bow to bow. The Mount Royal crowded the Hazelton into shallow water and slowly began to pull ahead. But Captain Bonser would not allow the loss, and recklessly rammed the Mount Royal. Captain Johnson lost control of his boat, which was carried downstream bow first.

In his triumph, Bonser wagged the Hazelton’s stern and tooted the whistle as they continued upstream. In a rage suited to the Wild West, Captain Johnson rushed out of the Mount Royal’s pilothouse and fired a rifle at the departing Hazelton.

The battle at Hardscrabble Rapids ended up in Marine Court. Johnson claimed his boat was deliberately rammed by Bonser, and Bonser insisted it was an accident. Both men were reprimanded—Bonser for ramming another vessel, Johnson for leaving his helm—and the case was closed.

Fate catches up

At the time of the settlement, Robert Cunningham was moving his freight on the Hazelton at a loss, and the HBC believed the competition between the sternwheelers was cutting into their bottom line. They offered to purchase the Hazelton from Cunningham, guaranteeing as well to move all his freight for free. Cunningham accepted, and the HBC took the Hazelton out of service, putting their former Captain Bonser out of a job. Bonser went south to work on the Fraser River, while Captain Johnson and the Mount Royal continued freighting on the Skeena.

In the summer of 1907, on a return trip downriver from Hazelton, the fate from its bad launch caught up with the Mount Royal. As Johnson piloted the vessel into the raging waters of Kitselas Canyon, a strong wind pushed it onto an island of rocks, impaling the bow. With the boat stuck, Johnson ordered a gangplank be placed across to the rocky island. Twenty-some passengers were safely evacuated, most not realizing the danger they were in, and some even reluctant to leave their plush quarters for a stormy rock.

Captain Johnson had just stepped ashore and intended to return to help his crewmen moor the Mount Royal to a tree when the boat suddenly turned, splintering her paddlewheel against the opposite bank. Wedged across the canyon like a dam, the violent current quickly turned the Mount Royal bottom up and hurtled her through the canyon. Six men died in the upheaval.

It took many hours for the people of nearby Kitselas to rescue the passengers from the rocky island. Bales of furs were found downstream and stretched out to dry. It is rumored that the Mount Royal’s safe, supposedly containing the gold of the prospectors leaving Hazelton, still lies at the bottom of the canyon.

The HBC built a replacement vessel, the Port Simpson, and in 1908 Captain Johnson returned to the helm.

The railway era

This was the beginning of the railway-building boom and many more sternwheelers took to the Skeena, some owned by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway for transporting their men and materials, some owned by railway subcontractors Foley, Welch and Stewart, and one owned by Pat Burns, supplying meat to the camps and settlements.

Captain Johnson was lured away from the HBC to work with the railway, organizing their fleet of sternwheelers supplying their construction camps. Captain Bonser returned to the Skeena to pilot the Inlander, a vessel owned by merchants at Kitselas and Hazelton.

In 1912 the railway bridge over the Skeena was completed and there was no longer a need for sternwheelers to move freight and passengers on the river. That fall, the last sternwheeler—the Inlander—left Hazelton and paddled down the Skeena, captained by pioneer Captain Bonser.

Large ringbolts remain attached to rocky walls and islands as testament to the sternwheeler captains and the First Nations men poling and paddling their way up and down the historic Skeena River route.