Too close for comfort

We were simply stopped next to some ranchland, the type common in Peace Country, with yellowed grass of late October, weather-beaten hay troughs, many head of cattle hoofing it about, and the forested hills orange-tinged in the distance. A red dirt road continued through the fields to the regenerating cut blocks we had to survey.

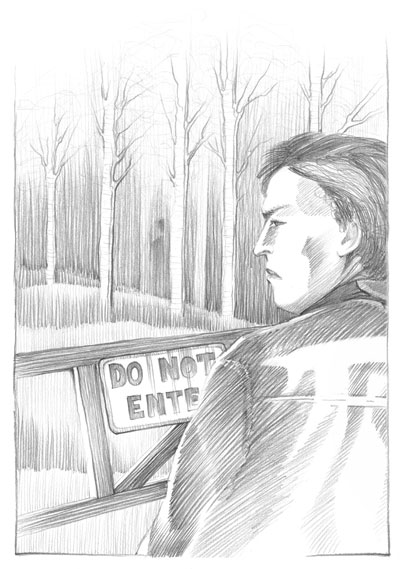

My co-worker was opening the gate when another pickup peeled around the corner and skidded to a halt next to us. A strong-looking man in a cowboy hat, probably in his late twenties, shoved open the door and rushed around the side to confront us. It was like being run at by a small bull.

“What’s your names?” he asked.

We said our names.

“Well, you’re both being charged with trespassing.”

“But what do you mean? Our client has permission to use this road.”

The man didn’t want to listen. Instead he shouted at us: “All you oil and gas workers are the same. You don’t care. And you don’t know how to close a gate!”

Even after explaining that we worked for a forestry consultant, he was still angry. “I don’t care who you are, you’re all the same.”

This semi-irrational outburst was symptomatic of a growing unease that has been transforming the Peace Country into Eco-War Country. In actual fact we were not so surprised to encounter this raging farmer, given what we had already witnessed throughout our 2007 and 2008 field seasons. A socio-ecological tension was brewing, of which as forest techs covering lots of ground, we were all too aware.

We had faced the usual ordeals of working in the woods that summer, like getting bluff-charged by a grizzly bear. In October 2008 we were to encounter a different kind of challenge: the close proximity of pipeline blasts.

The Politics of Naming

To call the bombing of Encana pipelines “eco-terrorism” is misguided, because the motives, as expressed in the threat letter sent to the Dawson Creek Daily News, had more to do with land usage and community health than an altruistic bid to save the environment.

“You have until Oct.11 of 2008 (Saturday 12:00 noon) to close down your operations…you keep on endangering our families with crazy expansion of deadly gas wells in our home lands…” The threat letter makes clear this is a local battle, not one based on grandiose ideology.

Nonetheless some militant environmental groups have recast the bombings as an expression of their own environmental movement. My reaction was more from the gut. I said to myself, “Boy, it’s not safe to work in these woods right now.” Turned out we didn’t have to—our manager found other blocks for us to survey while we waited for the situation to settle. Unfortunately, it never really did.

If part of what constitutes “terrorism” is scaring the heck out people, then the moniker at least somewhat applies. Everyone started acting a little more suspicious of each other after that first blast. Four blasts later, mega gas producer Encana decided to offer a $500,000 reward for information that would “put an end to the situation.” With stakes that high, everybody’s going to be taking a guess. It’s like a lottery: might as well report somebody.

It is, metaphorically, the detonation of the very frustration that everybody feels living in the hectic industrial north. Some people see the bombers as freedom-fighter heroes. Others condemn the acts as world-class terror. Either way, it is further evidence of the increasing global prevalence of militant activism. The fact that there exists such debate (and some of the online rants are really out of control) is indicative of a deeper conflict between industries and the individuals whose lives are affected by development.

“This statement today is to the person doing the bombing to raise their concerns so we can understand,” said the Encana PR rep at a media conference. If Encana were merely an innocent victim, they wouldn’t feel the need to explain themselves in this way.

The Writing on the Wall

The previous summer of 2007 there was a roadblock in Kelly Lake, and I remember reading an article in The Mirror about people feeling threatened by the increase of dangerous goods transportation through their communities.

In July of 2008, we heard some more strangeness on PEACE FM. Apparently a large quantity of TNT had “gone missing” near Chetwynd. Once the bombings started two months later, it was easy for any backseat investigator to put two and two together, though the RCMP have not acknowledged any link at the time of this writing.

Then there were the threats broadcast over our road channel. Instead of the usual loaded/empty kilometre calls, a voice came on LAD 2 asking for a radio check, then began to utter threats which sounded either read off the page or rehearsed, of which I still remember fragments: “From parts unknown…we are tired of you devils destroying our lands…we have no choice now but to introduce you to skull crusher…” The voice coming through our two-way radio sounded practiced, menacing, extremely creepy. It was poetic terrorism—the details of the threat were ghastly, uncomfortable to repeat.

The next morning, still unaware of the explosion that happened the day before, we parked next to a regenerating cutblock several kilometres down the road from the blast site. We were greeted by the idyllic aspen and cottonwood which inspire faith in sustainability. We began unloading our gear, pausing to sip our coffee and examine our maps.

I remember there was a gas lease on that block, and we had to sketch it onto our forestry maps. We find these leases so frequently that the silvery pipes seem a normal feature of the landscape by now, like banyan trees made of metal. Although these leases usually appear well-managed, it’s still unnerving working beside them, because the hydrogen sulfide that sometimes courses through their metal veins is invisible, scentless, and incredibly lethal.

Before we could proceed into the block, somebody interrupted us.

“Who are you? What are you doing here today?” a lady asked from the window of her big truck.

It felt weird having to explain ourselves in the woods, where solitude and freedom usually reign.

She took down our names. Then she told us: a bomb had been detonated on a major Encana pipeline the day before. Later we found out that investigators had phoned our office to make sure we were accounted for that day. By the time we returned to town after work, the news was public. For the first time probably ever, Dawson Creek was in the national spotlight.

Despite the potential severity, there is a hint of the comical about it all: the bumbling bombers who seem incapable of doing any real damage (knock on wood), and the affectations of oil and gas companies pretending to care about the bombers’ concerns.

Why do bad things happen in good places? Perhaps it is because good places are better able to deal with difficult situations.

Hopefully, like a broken bone, the fractures in Peace Country will, once healed, make the area stronger and more peaceful than it was before.