Stepping into the past:

The not-so-delicate sound of sheep hooves on a wooden boardwalk rouses me from a deep sleep. I open my eyes and try to remember where I am. I scan my surroundings for clues, but the rustic wooden walls don’t give much away. There is admittedly an old-timey quality to them, but the dim light and strange sounds from outside the window conspire to confuse me. Glancing around the room, I see a leather-bound book on a lace-covered table, a rifle mounted on the wall, an ornate wardrobe in the corner. It’s all strangely familiar, yet utterly foreign. I stumble to the window and see the offending sheep; beyond, a handful of buildings stand in the fields by the lake. Then I remember: I’m sleeping in a National Historic Site. This is Fort St. James.

The restored heritage site is designed to transport curious visitors through history, a kind of living museum. Open in the summer and catering largely to travelling tourists, the site employs guides who dress in period costume and are extremely knowledgeable about the storied history of the fort and the people who lived and worked there. But it’s not just for tourists: the old fort hosts special events throughout the year and is expanding its repertoire to attract regional visitors, school programs, and travellers looking for something more than a museum.

Last summer, Parks Canada piloted a new program at the site, offering bed-and-breakfast accommodation inside the site itself. You spend a night at the Officer’s House watching the sun drop below the horizon at the far end of Stuart Lake as a massive musk-ox wanders lazily around the fenced yard. Inside, you stoke the fire in the cast-iron wood-burning oven and cook your meal while listening to the bleating of sheep, clucking of chickens, and the occasional whinny of a resident horse. For one night, you live like it’s the 19th century, wandering through rooms filled with catalogued artifacts, sitting on original furniture and sleeping on a bed that Hudson Bay Company employees once slept on. In a weird way, it’s like time travel.

Trading through time

But what is the history here? As a European settlement, Fort St. James started its life in 1806. Set on the scenic shores of Stuart Lake, it was first called Stuart Lake Outpost. Founded by the inimitable Simon Fraser for the far-reaching North West Company, the fort was established mainly because of an abundance of fur-bearing animals in the area.

Prior to the entrepreneurial explorer’s arrival, the shores of Stuart Lake were home to Nak’azdli First Nation who, for millennia, had recognized the bounty of plant and animal life in the region. The Nak’azdli traded goods with other First Nations groups, travelling on trails—the so-called “grease trails”—later adopted by Europeans as trade routes. With the arrival of the fur trade and the trappings of “modern” life, First Nations engaged in trade with the settlers, setting up traplines in the thick bush to capitalize on the European fanaticism for fur products. Alongside European trappers, they caught and sold ermine, mink, marten, fisher, wolverine, lynx, river otter, three types of fox, coyote, timber wolf, black bear, and—the most sought-after creature of all—beaver.

“Made beaver was the currency of the time,” explains Cherae Brophy, an interpretive guide whose specialty at the site is the Trade House. “But it wasn’t exactly a standard currency,” she adds, and explains that there were a number of factors that affected the value of a beaver skin including size, condition, and quality. If you possessed high-level marketing skills, you could get more bang for your, er, beaver. “If you were a good talker,” she laughs, “you could definitely get a better deal.”

In 1821, the fort was acquired by the expanding Hudson Bay Company and it ran a lucrative trade for the company until the 1950s. It was then lovingly restored into the heritage site it is today. The restoration focussed on a single year: 1896.

Restoring the past

Within the overall site, there are five restored heritage buildings: the aforementioned Officer’s House, the Men’s House, the Trade Store and Office, the General Warehouse and Fur Storage, and the Fish Cache. During the summer season, a guide waits inside each building, ready to reveal to visitors the intimate history of the building and the people most closely associated with its operation in the late 1800s. The experience of wandering around the site, talking to the guides with their great anecdotal knowledge of the history here, is slightly surreal but absolutely captivating. There is no better way to have a history lesson than to live it.

In the Warehouse, interpreter Leon Erickson points out a map of the region drawn on a beaver skin, showing the trade routes from Stuart Lake. “Historically they wouldn’t write on a beaver skin,” he grins. “We did it because it looks cool.” When referring to historical events, he speaks in the first person. “We were responsible for making sure all these goods made it to Europe,” he says, gesturing expansively around him at the crates of goods and staggering volumes of pelts. “In 1896, the cheapest way to get from here to Europe was to go west.” He shows me the route on the beaver skin, connecting Stuart Lake to Babine Lake, then overland to the Skeena River and downstream to the Pacific. He laughs as his finger trails off the edge of the hand-drawn map. “To show you the whole route, we’d need a bigger beaver.”

In the Men’s House—the cramped quarters for trappers and traders—interpreter Rachel Robert talks about the people who wintered in the fort like they were her acquaintances. “George Holder was the maintenance man,” she says, pointing out his room. “He was a bit of a ladies man—you can see the pin-up above his bed there.” Holder was the only full-time resident in the building, she explains. Everyone else slept in a communal room upstairs for a few nights or a few weeks, either en route to another camp or fort, or while dropping off furs and picking up supplies. “Anybody could stay here,” she continues, “but since it was free, they would have to cook and clean up after themselves.” Newspapers line the walls, a cheap and effective way of keeping the cold drafts out. Plus, when the weather kept them trapped inside the small, cramped building—up to 30 of them at a time—the wallpaper served as a source of ready-made entertainment.

Back to the present

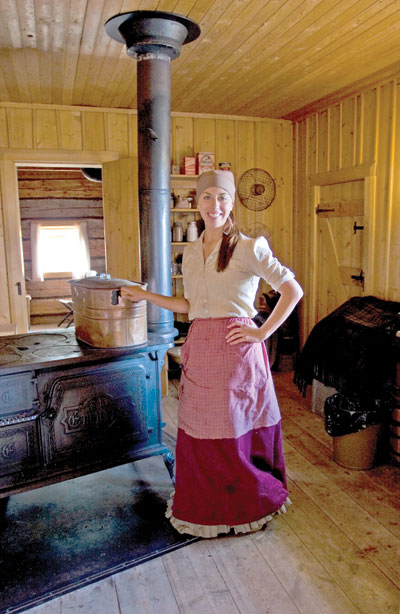

The sheep reluctantly wander off the boardwalk back into the field, and I eventually fall back asleep, but the bright sun wakes me up early. I get up and gather my things, blinking back the sleep as the sound of an axe breaks the stillness of the morning. Outside the Officer’s House, Kelsey Wheatley chops firewood, splitting kindling so she can light the big wood-stove. The scruffy sheep mill about as she prepares a meal fit for an officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Today, that’s me. “More coffee?” she offers cheerfully, proffering a steel carafe. “I brought my own from home,” she adds with a smile. A headscarf keeps her hair out of her eyes as she carries a mountain of food into the dining room. As I dig in, grateful for the food and enjoying the surreal feeling of being completely out of place—in my T-shirt I look like an alien here—I watch as Kelsey chases a plump sheep out of the hallway. She laughs, “If you leave the doors open, they just walk right in.” Like the sheep, that’s exactly what I’ve done: I’ve walked right into the past.

For more information about the site and its bed-and-breakfast program, check out www.parkscanada.gc.ca/fortstjames.