Warming up to new foods

Prince George Pinot Noir or Vanderhoof Voigner? How about a Sandspit Sauvignon Blanc?

Thanks to climate change, things are heating up all over BC. Could it be possible that northern vineyards, corn crops in the Bulkley Valley, apricot orchards in Terrace, and plums on Haida Gwaii could be a reality within the next 40 to 70 years?

If Dr. Richard Hebda, curator of botany and plant history at the Royal BC Museum of Natural History is right, the whole concept of eating locally in northern BC could become a lot more interesting. But will the changes be all peaches and cream?

Before anyone starts investing in grape vines or trading their hay crops for tomato seed, Hebda notes that other changes are just as fast in coming, making it difficult to predict just how northern BC will fare in the coming years.

According to Hebda, it’s not just a climate shift, but a grand-scale transformation northerners must prepare for, with changes not only in temperature, but precipitation, rising sea levels and ecosystem distribution as well.

Hebda has created a series of interactive maps now part of a permanent climate change display at the Royal BC Museum that outline some of the changes, not only to agriculture, but to plant and wildlife habitat and the cost of heating and cooling our homes.

Species on the move

Hebda provides three scenarios with varying degrees of impact: small change, most likely, and big change. According to his models, BC will transform into a very different landscape within a human lifetime. By 2050, species like red cedar could be dying of thirst due to longer, hotter summers along the coast. Hebda’s models show that this key coastal species won’t necessarily die off, but move to different regions, possibly as far away as Fort Nelson in the northeast corner of the province.

According to a 2006 provincial government report Preparing for Climate Change, “the average annual temperatures increased on the coast by 0.6ºC (about equal to the global average); in central and southern interior regions by 1.1ºC (twice the global average) and in northern British Columbia by 1.7 ºC (nearly three times the global average).”

The report goes on to say that “climate change scenarios suggest that during the 21st century British Columbia can expect average annual temperatures to warm by 2º to 7ºC, with northern BC continuing to warm faster than other parts of the province, and minimum daily temperatures continuing to warm faster than maximum daily temperatures.”

Hebda says the giant trees of the old growth rainforests will be among the first to disappear due to warmer, wetter and shorter winters, which will help improve the survival rate for insects, fungi and moulds that attack older trees. Garry oaks, which live on Vancouver Island and the southern Gulf Islands, could move north towards meadows along the Skeena River. He expects the province’s rare grasslands to expand and rare alpine ecosystems to be overtaken by lower elevation species.

But Hebda is not all doom and gloom. He is also keen to see people capitalize on new opportunities as agriculture diversifies. These new economic choices could help stabilize the economy during the transitions. “The question is what do we do about it? How do we respond?” he says.

New agricultural potential

British Columbians will have some unique opportunities to get involved in food production in the coming years, he suggests.

The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes some dire predictions for agriculture worldwide. Drought, changing rain patterns, shrinking snow-packs and less runoff in parts of Africa, Asia, areas of southern Europe and Australia could lead to food production being “severely compromised.” But in the short term Canada’s agricultural yield could increase by as much as 20 per cent, as long as potential issues such as pests, disease, invasive weeds and fire are curtailed.

According to the worst-case scenario revealed by his models, Prince George and areas west could have a climate similar to what the Okanagan is today by 2080. This would mean grapes, peaches and plums could become mainstay agricultural crops for present-day forestry and mining towns, as long as issues around water supply, land availability, and soil suitability and preparation are taken into account.

But climate change will not only have an impact on food-growing industries, but food gatherers as well.

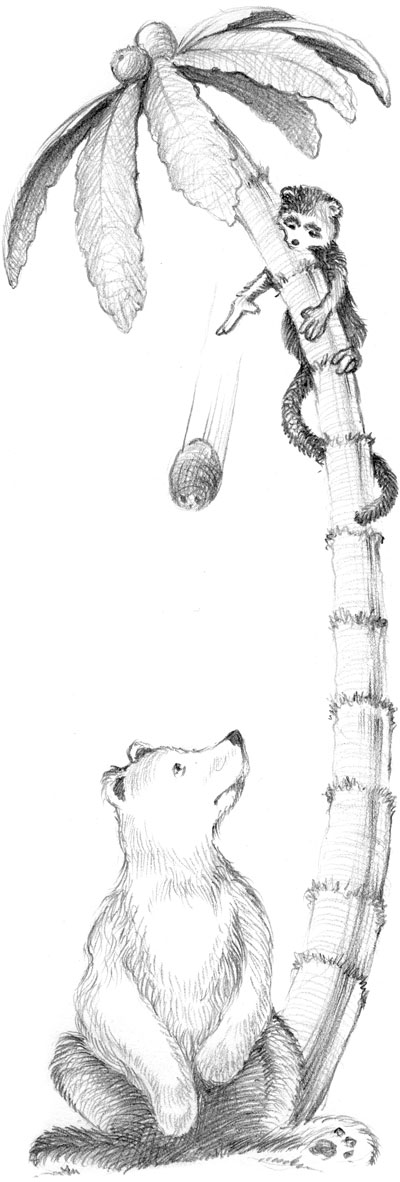

Hunters from eight First Nations with combined territories of 76,000 square kilometers of land in north central British Columbia are already noticing a change in the populations of porcupines and beavers out on the land. Jamie Sanchez, who heads up the Land Use Planning division of the Carrier-Sekani Tribal Council says the porcupine, especially, used to survive on the vast pine forests in the region. “But now it is all dead,” he says of the forest.

The mountain pine beetle has killed a large proportion of pine trees of a certain age in central BC, and it is still unclear what all these changes in pine-dominated ecosystems will mean for the traditional plant and animal harvesting. In the most obvious terms, the mountain pine beetle has brought more logging to Carrier-Sekani territories, and with this some economic benefits—but also problems like the use of herbicides to curtail growth of brush.

The pine beetle is also affecting the hydrology of the forest: dead trees no longer intercept precipitation, allowing it to gradually evaporate back into the atmosphere. Nor are there many live trees yet to suck up the moisture from the land.

Climate change adaptation

Sanchez says the Carrier-Sekani people, like other First Nations, have always been adapting to changes in their territories. Moose, for example were not native in much of the land, but the people have now put them to good use.

Sanchez says land-use planning must start taking into account the coming shifts due to climate change. He wonders whether replanting plans for pine beetle-affected areas are taking into account the different species that may establish with warmer climates. Are there opportunities for planting different tree or plant species for market or even for medicinal uses?

Sanchez adds that Indian and Northern Affairs Canada has started talking about climate change adaptation with various First Nations in the country, but they are assuming tribal councils and other forms of governance have the capacity to do something about these future issues.

Some climate change-related issues have already taken their toll—not just for First Nations, but anyone in the north. Last winter huge snowfalls took out power lines, ruining people’s frozen food supplies and collapsing smoke houses. Flooding along northern rivers wreaked havoc for those living near them, and roads and other infrastructure were also affected. The sockeye salmon run in the Fraser River system took a blow this year, too.

Hebda raises another issue that may come with warmer winters: reduced snow-packs. “Where will power come from?” he says, referring to BC’s reliance on hydroelectricity.

On another level, the Carrier-Sekani are taking a pro-active approach to climate change issues. Vice tribal chief Catherine Lessard has already spoken out about several oil and gas development projects in BC’s north, in part due to their role in increasing greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Pembina Institute, at least six large-scale pipeline and energy projects are proposed within the next five years in north-central BC. With pipeline infrastructure in place, areas like the Nechako and Bowser Basins could be more easily opened to oil and gas.

“Our communities already see the impacts of climate change first-hand. The mountain pine beetle epidemic is impacting our forests and our communities. Bringing oil, gas and pipeline development into our territories would cause further significant cumulative impacts that could drastically alter our way of life,” said Lessard.

Dr. Hebda has some advice for ways to reduce the impacts of climate change:

*Reduce emissions*Travel less*Restructure cities and urban areas into self-reliant communities*Restore “the forest” on every lot (e.g. replace lawns with forest and garden)*Restore natural wetlands, ponds, and riparian areas*End the conversion of natural lands—humans have already taken enough.*Ensure food security: protect the Agriculture Land Reserve; experiment to diversify crops*Evaluate projects based on carbon emissions*Stop needless consumption. Empty consumerism = C02 emissions*Embrace the “Slow Movement” (www.slowmovement.com)*Foster wise individual choices*Work close to home, thereby gaining time, and saving money to reinvest in BC*Don’t believe in a “techno-fix”—there are no easy solutions.