Missing the mark:

There’s something about bears, those fierce-yet-furry sovereigns of the food chain, that tends to bring out ursine behaviour in even the most docile mammals. So perhaps the province should have expected, when it expanded no-hunting areas for black and grizzly bears this summer, that the decision would be likely to bring growls from hunting and conservation groups alike.

In early July, BC’s Environment Minister Barry Penner announced that an additional 470,000 hectares would be closed to grizzly bear hunting and more than 22,000 closed to black bear hunting on the central and north coast, bringing the total area closed to grizzly hunting along the central and north coast to 1.9 million hectares — or about two percent of the province’s area.

It’s a decision that Pacific Wild conservation director Ian McAllister describes as “far too little, too late.”

The move has been a long time coming, McAllister says, harkening back to a 1995 announcement by then-premier Mike Harcourt that a system protecting core areas would be established across the province, linked by functioning travel corridors.

“We all said, ‘This is a great first step.’ The short story is, nothing has been done since ’95,” McAllister says. Grizzly Bear Management Areas (GBMAs) were never identified and trophy hunting of grizzly bears increased, he says.

Isolated zones

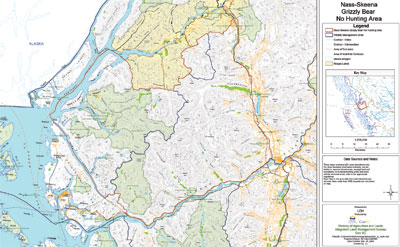

The Liberal government recently designated the Annuhhati, Nass-Skeena and Khutze-Kitlope-Kimsquit Upper Dean-Tweedsmuir as grizzly bear management areas, which are closed to grizzly bear hunting.

While it might be a move in the right direction, McAllister points out that these isolated no-hunting zones don’t incorporate adequate movement corridors, putting the wide-roaming bears in danger whenever they wander outside the protected area: “They’re not large enough to provide full protection of a grizzly bear’s range and seasonal movement patterns,” he says, adding that the restrictions expire in 10 years time. “It would be business as usual, with trophy hunting.”

The province recorded a total of 1,466 grizzly bears killed by hunters between the 2004 and 2008 hunting seasons, the peak occurring with 366 grizzly deaths in 2007, followed closely by 319 in 2008. During the same timeframe, between 3,000 and 4,000 black bears were killed every year by hunters.

Grizzly populations are notoriously hard to estimate, with numbers fluctuating since the 1970s. At that time, it was believed there were just under 7,000 grizzly bears in the province; in 1990, that number doubled. Today, government estimates put the province’s grizzly population at about 16,000 and black bears in the neighbourhood of 100,000, but those estimates—and the science used to determine them—are questioned by conservationists.

“We absolutely dispute those numbers. We don’t know how many bears there are, we just know the province’s methods are unscientific,” McAllister says. “The numbers aren’t nearly as important as the trends, and the trends are showing the bears aren’t showing up in key areas now.”

The announcement also doesn’t address issues like salmon depletion, the impacts of tourism and habitat destruction, which McAllister blames for lower bear survival and reproduction rates. Considering the number of variables, and the lack of concrete evidence surrounding bear population numbers, he argues that simply halting the hunt would be the most sensible move.

Shrinking boundaries

Grizzly bears once roamed as far south as Mexico and east into Manitoba. Today, the eastern boundary of their range sits just over the Rocky Mountains in Alberta, where a similar battle is playing out over the province’s roughly 500 grizzly bears—a number significantly lower than initially projected by government.

Under Alberta’s Wildlife Act, any species with less than 1,000 mature, breeding individuals should be listed as threatened, but the government has refused to recognize the grizzly as such. The move would bring an immediate stop to the annual hunt.

Instead, after ongoing public outcry from conservation groups, Alberta placed a moratorium on grizzly hunting in 2006 until more accurate population numbers could be determined through DNA testing. Initially scheduled to last three years, the hunting ban has been extended until research is complete, a process currently expected to last into 2010, according to Alberta Sustainable Resource Development communications manager Dave Ealey.

The British Columbia government’s recent restrictions also extend to white-phase black bears, commonly known as Kermode or Spirit bears, anywhere in the province. This prohibition previously applied to Kermode bears found in coastal regions; penalties are up to $100,000 and one year in prison for violation under the BC Wildlife Act.

Up in arms

Asked how hunters would suffer from the restrictions (would it be a personal or financial loss?), BC Wildlife Federation wildlife allocations chair Wilf Pfleiderer replies, “It’s just loss of opportunity because those areas are no longer available for hunting.”

The hunting advocacy group is up in arms about what they say is a lack of representation in the planning process and a decision that goes against previous recommendations. “We don’t support the increase in the number of grizzly bear management conservancies,”

Pfleiderer says, adding that the expanded restrictions go against recommendations made by an independent review panel in the 2003 report Management of Grizzly Bears in British Columbia, which he argues recommended only one GBMA per ecoprovince. (An ecoprovince is a geographical area with similar ecological features—BC has nine of them.)

In fact, the panel recommends “at least one large, benchmark GBMA within each terrestrial ecoprovince in BC,” along with small ‘linkage’ GBMAs intended to enhance bear movement across human-fractured environments, and medium-sized GBMAs serving as protected areas within larger exploited habitats.

“We believe in conservation, but the recommendations were provided by this peer review panel. There is a benefit for taking a harvest that is sustainable, and our grizzly bear populations are very healthy,” Pfleiderer says, citing safety issues as one reason for continuing the hunt: “The bears lose their fear of humans.”

He adds that grizzly bears are being seen in areas where they’ve not previously been reported, such as Vancouver Island, the Okanagan and the Cariboo.

First Nation and conservation groups alike have decried the hunt, arguing that there is more economic opportunity in bear viewing and wildlife tours than trophy hunting. Although a representative of the Coastal First Nations Turning Point Initiative could not be reached for comment, the organization—representing 10 coastal First Nations in their efforts to build a conservation-based economy—has called on the government to halt the annual hunt altogether.

“Why isn’t the Campbell government responding to First Nations on this issue?” McAllister asks. “From an economic perspective, a live bear is worth far more than a dead bear.”