Dino-mos:

Tumbler Ridge was once a prehistoric party spot. The soirée wrapped up some 65 million years ago, but its remnants—still scattered about like as many discarded empties—today make it a gathering place for bone buffs, dino-nuts and tyrannosaurus geeks.

Their words, not mine.

Alan Byers and Tyler Shaw are a formidable dino duo as they spar off against one another in their enthusiastic dialogue about local pre-history. Byers, a University of Victoria geology student studying micropaleontology, is a summer employee with the Tumbler Ridge Museum Foundation. Shaw is the museum’s chief technician and a Master of Science candidate specializing in paleontology at the University of Alberta.

“I’m told I can find trilobites up in the mountains. If there’s one thing I love, it’s a trilobite,” Byers says, enthusing about his summer job. In the evenings, he volunteers his time to guide visitors on dinosaur-track tours. “Talking about geology and paleontology, going on hikes—this is something I do for fun anyway!”

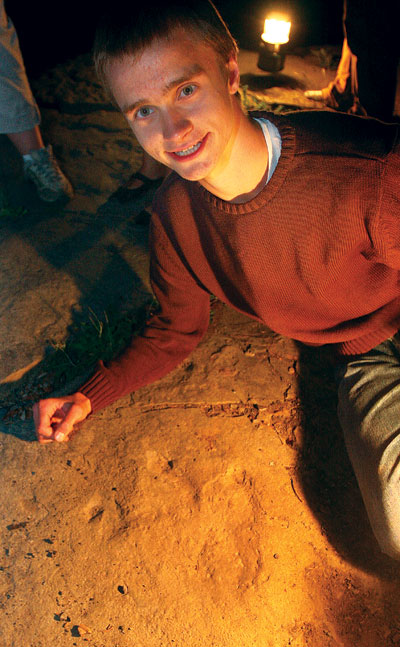

It’s dusk and, as the day’s final light drains from a glowing blue sky, lantern-light casts its orange glow across sandstone banks of the Wolverine River. Once one’s eyes adjust, the slanted shadows illuminate faint imprints in the stone—footsteps made by a dinosaur more than 100 million years ago. Known as trackways, the marks left by these meandering prehistoric creatures as they went about their daily business reveal details about the animals’ habits, their gait, even the patterns on their skin.

Although still largely unexplored, Tumbler Ridge is home to 95 percent of the province’s fossil vertebrates found to date. On the many hiking trails in the area, it would be easy to stub your toe on a fossilized footprint or a coprolite—fossilized dinosaur poop—without even realizing it. Needless to say, Tumbler Ridge is leading the charge when it comes to paleontology in the province.

’Saurus-dipity

Paleontologist Rich McCrea discovered the Wolverine River trackways in 2001, but evidence of prehistoric activity in the Tumbler Ridge area was brought to the public’s attention a year earlier by then eight-year-old Daniel Helm and friend Mark Turner. The boys made their discovery while tubing rapids on Flatbed Creek.

“Because they’re a bit more turbulent, we fell off our tube,” Daniel remembers. So, like most resilient young boys, they got off to walk back up the rocks and try again. When they saw the prehistoric imprints, they didn’t need to think twice. “When we saw them, we immediately thought ‘dinosaur,’ because that’s what kids think.”

Daniel’s father, local hiking-guidebook author Charles Helm, wasn’t so sure. As Tumbler Ridge’s family doctor, he provided a scientifically skeptical explanation, writing the find off as “erosion features.”

Daniel was insistent and contacted McCrea, then with the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta. The pair corresponded by email, Daniel sending images and measurements of the tracks he’d found. McCrea confirmed them as belonging to an ankylosaur—a “prehistoric 4 × 4” designed for travelling over mountainous terrain.

The following summer, McCrea made a trip to Tumbler Ridge. “While the boys were getting a picture taken for Canadian Geographic Magazine, I was working on getting the physical characteristics of the track surface,” McCrea remembers. “I went to put my compass down and almost put it on top of a dinosaur bone.” It was BC’s first dinosaur bone discovery.

Digging into pre-history

Nearly 10 years later, McCrea and his wife Lisa Buckley live and work in Tumbler Ridge. In 2003, the couple started the Peace Region Pelaeontology Research Centre and in 2006 the Dinosaur Discovery Gallery opened to the public.

“We are pretty much it for vertebrate paleontologists for the province,” Buckley says. “If it has a backbone, then we study it.”

In 2004, the couple started walking exposed rock outcrops, scouring the terrain for paleontological evidence. When they found a bone eroding from a hillside, they didn’t realize at first the magnitude of the discovery: “We didn’t know how much of the animal was in the bank until we started digging,” Buckley says.

As they began to expose the hadrosaur, the researchers realized its skeleton was still relatively intact. Through the recent field season, crews worked to excavate the duck-billed dinosaur from its hind-end up, hoping to discover its head, presumably buried further into the slope. By mid-August, as the field season wrapped up, the skull — if it exists — was still uncovered.

Until the excavation is completed, little is known about the animal, but the find could be significant. As it stands, the paleontologists know the skeleton is more than 50 percent articulated—or intact—making it a first for BC. “When we found two vertebrae together, that was BC’s most complete dinosaur to date,” McCrea says.

“There’s no other competition.”

Even more exciting is the potential for the discovery to be a new species to science. Dating a relatively youthful 75 million years old, the hadrosaur is more recent than other fossils in the area. As Buckley notes, “A couple million years is enough time for a new species to evolve.”

But what they do know for sure, according to McCrea, is that “the tyrannosaurs had a party.”

Scattered about the site, the researchers have already found 40 tyrannosaurus teeth — half the total number in the average tyrannosaurus head. Rather than the likelihood the herbivorous hadrosuar was scavenged by one meat-eater with severe dental deficiencies, McCrea speculates a large number of tyrannosaurs ripped at the decaying animal, resulting in the skeleton’s detached leg and scattered vertebrae, particularly in its upper body.

The excavation will continue when the field season starts up again next June, but could take another year or two to complete.

Fossil free-for-all

In the meantime, the site’s exact location, somewhere in the Tumbler Ridge area, remains highly secretive. With no protective legislation for fossils in BC, the team has to be leery of recreational dino-nuts helping themselves to souvenirs from the location. Unlike Alberta, which has 150 years experience excavating dinosaurs, BC is still relatively unexplored territory when it comes to paleontology and its politics reflect this; it is the only province with substantial fossil resources, but no legislation.

Now governed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands, fossils were until 2005 considered a mineral and administered under the Mineral Tenure Act. In 2004, the province responded to conflict among scientific, recreational and commercial fossil interests with a report that made recommendations on protecting BC’s fossil resources. This led to the Fossil Management Framework, which uses existing legislation to protect and regulate fossil resources.

“Paleontologists prefer something that’s more specific to the fossil, but it’s a good stepping stone,” McCrea says, throwing in a dinosaur metaphor to describe the current consequences of compromising a fossil site: “I don’t think that what could be done has much teeth.”

Regardless of human interference, many prehistoric sites in northeastern BC exist only for the blink of an eye, paleontologically speaking. McCrea suspects the tracks discovered by Daniel and Mark at Flatbed Creek had only been exposed for several years, as the river peeled away layers of rock to reveal the indentations. Likewise, over the next decade new sites will be uncovered, even as current ones are disappearing to erosion.

In the meantime, enthusiastic researchers in Tumbler Ridge will be excavating, studying and cross-referencing local finds in the hopes of piecing together new information about life in northern BC long before its current inhabitants were around. By comparing trackways with skeletons, researchers are learning not only how the animals died, but how they lived as well.

“Tumbler Ridge has a lot of time periods exposed in the rocks for footprints,” Buckley says. “But unless you have the skeleton to go with them, you don’t know who made the footprints.”

Conversely, McCrea adds, “The excavation we’re currently working on is a dead animal. You can learn a lot from it, but there’s a limit. Trackways tell you a lot about the animal—how it moved, what environments it frequented and what other animals it might have interacted with.”

While scientists dig deeper for answers, what does seem certain is that northern BC likely has many paleontological discoveries beneath its rich soil, waiting to be uncovered.