Secret weapon

During the final year of World War II the Canadian army and American military attempted to silence rumours of an airborne threat floating over the Pacific Ocean from Japan. They reasoned that if the “enemy” did not know their weapons were successful they would assume failure and cease launching the so-called “fire balloons.”

The Japanese balloons, carrying incendiary and anti-personnel bombs, were meant to instil panic and cause fires and destruction when they randomly touched down. When airborne, the balloons were over 75 feet tall and 35 feet in diameter and capable of carrying just over 200 pounds.

Captain Charles A. East described the balloons in White Paper; Japanese War Balloons of World War Two. “The balloon envelopes were made of five-ply laminations of very fine rice paper, pieced together in more than one hundred tapered segments.” East wrote that over 1,500 feet of rope carried a chandelier rack suspending 32 sandbags of ballast and four incendiary bombs, with an anti-personnel bomb attached under the centre.

The balloons were inflated with hydrogen gas and set off into the prevailing northwest winds of the upper atmosphere. They were ingeniously designed to drop a ballast bag when the balloon dropped in elevation, thus rising again and travelling farther. The balloon repeatedly lost and gained elevation, eventually dropping all its sandbags and falling randomly somewhere on North America.

The Canadian military wanted no-one to see the weapon: the balloons were to be recovered covertly by specially trained military personnel wearing protective gear and taking all steps necessary to remove the evidence. As a bomb-disposal officer stationed in Prince George, Captain East had a very busy year tracking down and disarming the Japanese paper balloons that landed in northern BC.

Takla Landing

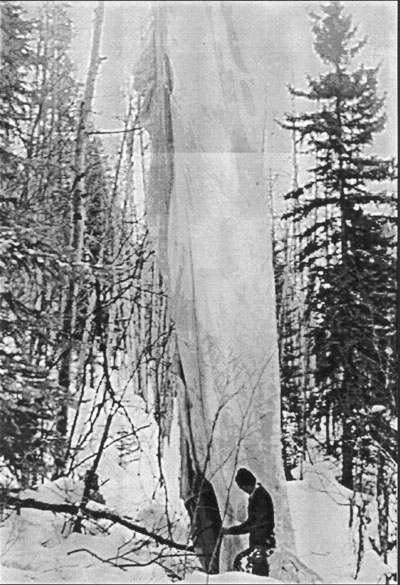

Captain East’s first operation was to Talkla Landing, in February, 1945. This was the second balloon found in North America. After a harrowing flight on a ski-equipped Norseman aircraft, East and Corporal W.V.L. “Smitty” Smith hired Olaf Bjorinsen and his dog team to take them to the balloon crash site. The men camped on the Bear Lake winter trail under spruce trees and tolerated the howling of wolves. Captain East wrote that early in the morning they located the balloon caught on a pine snag and tangled over the top of 16 other pines.

This was their first mission. They had been warned that a lightweight soldier may have been transported in the balloon as well, so they lay on their bellies and searched the site with binoculars. Both men thought the idea of a human surviving the journey and the landing very unlikely.

“Our instructions were that we were to wear coveralls, anti-gas boots, rubber gloves and surgical masks during the recovery operations,” wrote East. He attempted to follow the rules, but the deep snow and hidden snags ripped his boots and tested his patience.

The two men managed to get the chandelier down. They bagged up samples and tried to remove the balloon from the treetops, but couldn’t. Contrary to orders, they asked for help: William George, then 17, nimbly climbed the trees and tossed the balloon down. East told George that the balloons were Japanese and dangerous because he “...felt that it was safer for George to know the truth for his people, rather than have someone killed out of curiosity and incorrect information.”

Cedarvale

Just when the army thought the Japanese balloons were a well-kept secret, a full passenger train on the CNR line near Cedarvale witnessed a balloon drifting over the Skeena River. East and Smith were dispatched from Prince George, taking a jeep along the rough winter roads through Burns Lake, Houston and Smithers. After a short sleep there and an engine repair in Hazelton, the men went as far as the early road was plowed, to Kitwanga. There they abandoned their vehicle, took a boat across the Skeena and a CN speeder car down the tracks, arriving late at night in Cedarvale where they were welcomed into the home of Mr. and Mrs. Essex.

In the morning they crossed the Skeena and engaged Phillip Sutton to guide them up the Seven Sisters to where the balloon was last sighted. Sutton found the balloon “...suspended between three big trees, forming a huge canopy.” East recalled, “a maze of ropes trailed down from it to the chandelier . . . two bombs were suspended opposite each other.” East began walking around the balloon studying the circuits and the unexploded bombs when “...the heel of my snowshoe snagged something and I looked at a black object projecting from the snow. With my hands I dug the snow from it to reveal the tail fins of a bomb.”

Corporal Smith ascended the trees with climbing spurs, belt and rope. The men managed to untangle and gently lower the bombs where Captain East “...untapped the demolition charge and cut the fuse leading to the detonator.” The anti-personnel bomb proved to be the biggest scare in Captain East’s career. As he was holding the bomb in his hands and carefully using his special magnetic microphone and earphones, a branch falling from the treetops landed in the snow right behind him. After that scare the men disarmed the bombs and packed all the evidence in Sutton’s moose hides for the horses to pull down the mountain.

The Cedarvale balloon was shipped to “Defence Research” in New York for studying.

Balloons all over

Captain East and his team disarmed balloons at Babine Lake, Dome Creek, Collin Lake (southwest of Houston) and as far east as the Rauch Valley (near Valemount). Balloons landed at Barkerville, Fort Ware (at the head of the Finlay River), Chilako River, the Gang Ranch and Chilko Lake. Balloon fragments were found in Vanderhoof and were spotted near Quesnel, at the foot of Mount Robson and at Red Pass Junction near Jasper. In August 1945 one was reported at Pinchi Lake. Two other sightings turned out to be American weather balloons.

Captain East’s last mission, to Goat River in October, 1945, was a false alarm: the balloon turned out to be a split and folded-over tree with a large strip of bark fluttering in the breeze.

East describes this time of his life as exciting. He handled many Japanese bombs and escaped with no injuries. He says he may have been more than just skilled, more than just lucky: he ponders the fact that the bombs were never booby-trapped as the Japanese had the means to rig up tricks that would have proved fatal to anyone attempting to disarm a balloon. Germ warfare was also never part of the balloons, although military intelligence at the time considered it a threat. East “had the feeling these bombs were not meant to inflict horrific damage,” and that the “enemy” was exercising restraint in its weaponry. “They [the balloons] were not the product of a savage war machine.”

“There were no ribbons, medals or badges handed out to any of us, nor did we receive any special recognition for the fact that our small group was the only operational force of the army in Canada in actual contact with enemy operations on Canadian soil.”Captain East lived in Prince George for many years before retiring to Vernon. He died in January, 1995.