Mennonite migration, 1940

In 1940, Saskatchewan was still struggling to recover from the depression and was experiencing a severe drought. Soils were parched and seeds wouldn’t germinate. With no crops to grow, farms and farm families were suffering. “Drought, dust, heat, grasshoppers, western equine encephalitis and army worms drove farmers to desperation,” according to the Saskatchewan Archives Association.

At the time, the Saskatchewan government was providing relief payments to the suffering families and wanted to move people off the drought-stricken prairie to raw land that could be farmed. In BC, meanwhile, the government wanted to see more people settled in the northern part of the province. Saskatchewan and BC worked together to move distressed families off the prairie and onto land that the BC government wanted to develop near Burns Lake.

“The government chose families who had experience, pioneering qualities, adequate livestock, and machinery,” says Conrad Stoesz, archivist at the Mennonite Heritage Centre in Manitoba. The Mennonite families exemplified these qualities.

Stoesz, who has written about the migration of Mennonites from Saskatchewan to Ootsa Lake and Cheslatta south of Burns Lake, says that in total 56 adults and 153 children left their prairie home to homestead in this area of BC. The Saskatchewan government paid for their transportation to their new home.

Helen Rose Pauls writes in The Way We Were: First Mennonite Church, Burns Lake that “the first Mennonite settlers in the Burns Lake area were Old Colony Mennonites from the Hague–Osler and Toppingham areas of Saskatchewan.” Their 800-mile move to Burns Lake was not easy. All their household effects, large farm implements (including tractors and entire blacksmith outfits), livestock, and they themselves had to be moved on the train. On the days leading up to the Mennonites’ departure the yards surrounding the prairie railway stations were crowded with wagons, tractors and horse-drawn farm implements.

Impassable roads

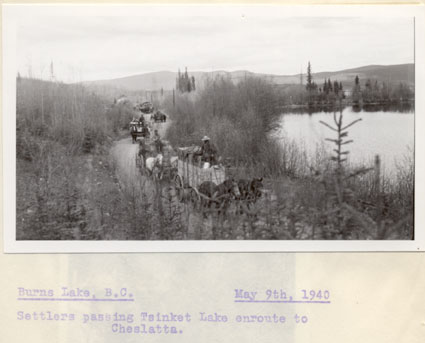

Photographs show that on May 2nd large groups of Mennonites gathered at the railway station in Toppingham, Saskatchewan; they arrived in Burns Lake about a week later. “The families came with various items such as ploughs, harrows, cream separators, horses, cattle, and chickens,” says Stoesz.

At Burns Lake they unloaded the 44 boxcars and drove trucks and wagons along the rough dirt roads out of Burns Lake. Trucks carried them for the first 30 miles, but the roads soon became impassable and the Mennonites turned to their horses and wagons. A dairy newspaper following their progress reported that 14 miles of roads had to be re-built to permit the Mennonite wagons to pass; their first 10 days in BC were spent working on the roads.

Another crowd of Mennonite families assembled at the Osler station in Saskatchewan the following month; a week later they were following the same dirt road—now improved by the families who preceded them—south from Burns Lake. The Mennonites were not going to existing farms with finished houses; theirs was the marginal raw land that earlier Southside settlers had passed over.

Although the Saskatchewan government provided the re-located Mennonites with support rations for up to three years, the families were remarkably quick to get established and comfortable in their new landscape. “Upon arrival, families toured in small groups with BC and Saskatchewan government officials to select specific tracts of land,” says Stoesz. “Timber permits were secured allowing the families to obtain trees for building shelters and fences.”

The settlers lived in temporary housing while they cut and peeled logs to build their homes and outbuildings. Photographs show that some erected prairie-style tepees for the remaining summer months. Pauls writes that, upon arrival in their new home, the Mennonites constructed two churches in Cheslatta and Grassy Plains. These were used as private schools for the children during the week. Working together the families built log homes and log barns, cleared, cultivated and cropped acres of land. Those who didn’t have homes built lived with each other in temporary shelters until the following spring; one young family intended to spend their first winter in a granary they had brought with them from Toppingham.

Successful settlement

An agent from the Department of Colonization and Agriculture of the Canadian National Railway in Winnipeg followed up with the Mennonites, visiting them in the summer of 1940 and assessing their “chances of success” in the Burns Lake district. He toured the area and recorded his observations of the Mennonites’ situation. Frank appraisals were made of the settlers’ character; comments ranged widely from “settler is a good type” to “it is only through the influence and active assistance of his two relatives that he will eventually succeed.” Some men found work cutting hay at established farms in the area, including the Bostrom Ranch, a well-established farm at Grassy Plains, where Mennonites J. Schapansky, Herman Dick and C. Giesbrecht cut and put up the entire crop of timothy hay. Of the 160 loads of hay, Bostrom gave the workers half the crop.

The Saskatchewan government also sent an agent to check on the settlement of Mennonites south of Burns Lake. He noticed that the crops sown in June failed to reach maturity and would be good for animal feed only. Archivist Stoesz notes that, “in October, friends in Saskatchewan sent extra feed for the winter.”

Stoesz refers to a “Directors Audit Report, Burns Lake District Office” which shows that the population of the Burns Lake region in 1940 was approximately 10,000 and that 30 percent were part of the Mennonite community. The governments of BC and Saskatchewan took note of the successes of the Southside Mennonites; Stoesz adds that “in 1941 another 25 families were relocated to the Vanderhoof area of BC.”

During a later inspection, the CNR Department of Colonization and Agriculture noted that, “by 1942 there were 400 acres under cultivation with crops giving good yields; they had big gardens and comfortable homes and no assistance was needed.” The Mennonites had clearly settled in and were thriving on their new homesteads.

Helen Rose Pauls writes that after the first immigration of Mennonites in 1940, others followed: “Mexican Mennonites moved to the area to work in the mills, as did Sommerfelder Mennonites from the prairies and General Conference Mennonites from southern BC.” There were also affiliations with the Eastern Pennsylvania Mennonites.

The provinces of BC and Saskatchewan saw the re-settlement of the prairie Mennonites as “highly satisfactory” and, had the depression continued, more settlements would have been established to relocate more Mennonites. “This plan,” says Stoesz, “provided drought-stricken families with a new start, cash-strapped provinces with a way of decreasing relief payments, and a way for BC to increase its northern population.”