100 Mile Diet

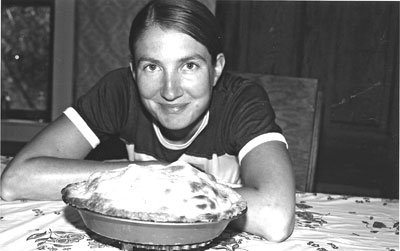

It’s strawberry season. James and I are crouching between long rows of the bunchy green plants, plucking the big berries and dropping them gently into small buckets. We imagine their future with cream and in pies. I lick the sweet red juice from my fingers. “If I make jam we can have strawberries all year,” I say. James asks with what, exactly, I plan to make the jam. Sugar? One of the planet’s most exploitative products, shipped in from thousands of kilometres away?

“But what,” I reply, “will we eat all winter?”

This may seem like a peculiar question in an age when it’s normal to have Caribbean mangoes in winter and Australian pears in spring. However, on March 21, the first day of spring last year, we took a vow to live with the rhythms of the land as our ancestors did. For one year we would only buy food and drink for home consumption that was produced within 100 miles of our home, a circle that takes in all the fertile Fraser Valley, the southern Gulf Islands and some of Vancouver Island, and the ocean between these zones. This terrain well served the European settlers of a hundred years ago, and the First Nations population for thousands of years before.

This may sound like a lunatic scheme, but we had our reasons. The short form would be: fossil fuels bad. For the average American meal (and we assume the average Canadian meal is similar), World Watch reports that the ingredients typically travel between 2,500 and 4,000 kilometres, a 25 per cent increase from 1980 alone. This average meal uses up to 17 times more petroleum products, and increases carbon dioxide emissions by the same amount, compared to an entirely local meal.

So our rules, when we began, were purist. It was not enough for food to be locally produced (as in bread made by local bakers). No. Every single ingredient had to come from the earth in our magic 100-mile circle. Our only “out” was that we were allowed to eat occasionally in restaurants or at friends’ houses as we always had, so that we did not have to be social outcasts for a year. And, if we happened to travel elsewhere, we could bring home foods grown within a hundred miles of that new place.

Between us, we lost about 15 pounds in six weeks. James’ jeans hung down his butt like a skater boy. He told me I had no butt left at all.

At the end of these desperate six weeks, we loosened our rules to include locally milled flour. Surely, 100 years ago, farmers grew wheat in the Fraser Valley to supply local needs, but the global market system is a disincentive to such small-scale production.

Then there was a lack of variety. For a couple of weeks we wondered if it would be possible to go on with this crazy diet. We could walk into, say, an IGA and look down all those glittering aisles, and there was not a single thing we could buy.

Then we decided to go north, to seek out the bounty around our off-the-grid cabin in northern British Columbia—Doreen, 50 kilometres northeast of Terrace, accessible by train only.

The Hundred-Mile Diet hits the road

The following excerpt was first published online at www.thetyee.ca, as part of a series on the Hundred-Mile Diet. Log on to read other installments about J.B. MacKinnon and Alisa Smith’s attempts to eat well, and their reminiscing about moral diet choices and the involuntary weigh loss that comes with living more than 100 miles away from sugar and other sweet-tooth cravings.

To be honest, we thought we’d cut ourselves some slack. We were going to northern British Columbia, for god’s sake. We could hardly be expected to stick to some monkish vow to eat only those foods produced in a hundred-mile radius. Environmental sustainability would, like us, be taking a summer holiday.

Where are we headed exactly? Let’s call it Devil’s Elbow, B.C., which is, in fact, one of its names. It’s not quite a ghost town (population: 1), but you’d agree with that description if you heard some of the noises that haunt the 80-year-old homestead shack we’ve been in for a month. The place is like a visit to the doomsayers’ version of the End of Oil: no road access, no power, no sewage, no cell signal, no running water except for a glacial river. I think we could be forgiven for fudging our Hundred-Mile Diet rules. I haven’t used toilet paper for weeks (ah, the double-ply softness of thimbleberry leaves); surely I could allow myself a couple bags of Californian granola.

What has amazed us, though, is just how achievable a Hundred-Mile Diet actually is here on the 55th parallel—and beyond. There is a tendency, south of 50, to imagine everything north of the Lower Mainland and Okanagan (they make wine there, right?) as a hinterland of thick forest, early frost, and people who prefer shooting road signs to planting vegetable gardens.

Well, witness these two markets. Nothing we’ve seen in Vancouver can compare. No, you can’t get on-site massage or hand-blended chakra-aligning teas, but you can get an incredible supply of good, real food. As a rule, it is both cheap and enormous—cabbages larger than your head, lettuce leaves like serving platters, shrubs of local herbs. (At a farmgate stop in the Kispiox Valley, everything we bought was the biggest we’d ever seen, from greens to beans to berries.) Farmers themselves, in varieties from German to Tsimshian to former-Vancouverite, point to the rich alluvial soil, rainforest rain, and 20-hour summer days. Others hint at ancient deposits of sasquatch night soil.

Devil’s bounty

The fact is, we found more at these “northern” markets than we have in Vancouver. There is, however, the same sense that most of the shopping is done elsewhere. One woman was surprised to find “young people” buying her beet greens; two Portuguese-Canadian farmers simply could not believe I knew how to cook favas. As with everywhere else, the grocery stores do brisk business in organic apples from New Zealand (really—we checked) and processed foods while the freshest market produce imaginable fades into a kind of quaint remnant economy.

Gloomy observations aside, by the time we’d hopped the train for the 40-minute ride to Devil’s Elbow, we were stocked: potatoes, summer savoury, celery, zucchini, a jar of pickled eggs, smoked sockeye salmon from the famous Wet’suwet’en gaff-fishing site at Moricetown, cabbage, lettuce, cucumber, green onions, yellow onions, honey, cauliflower, yellow and ribbon green beans, fava beans.

All of it was huge and half the price of either the chain stores or Vancouver’s markets. Of special note: tomatoes from Smithers, the best either of us had ever had, from a nearly silent old man named Willie; and packs of dried pinto and fava beans grown outside of Terrace. These are the first dried beans we’ve seen at any market since we started the Hundred-Mile Diet, and we cleaned the guy out to pack them home for vegan meals.

Supersize me

Of course, the provisions don’t stop as you enter the wilderness—it’s just that they aren’t lined up on fold-out tables. We had already picked an entire cereal box of Saskatoon berries outside the small town of Telkwa (did I mention these were the largest we’d ever seen?), and they kept well, un-refrigerated, until we’d eaten the whole bunch. In Devil’s Elbow, there were fresh opportunities: thimbleberries, highbush cranberries, huckleberries, dandelion greens.

We’re far from bush masters, but we know a handful of wild foods, and with our market vegetables and some stocks from past years (yes, as a matter of fact I was tempted to buy the Unabomber biography I saw in Smithers), we were living well—and living Hundred-Mile. There was also the old homesteaders’ orchard—still churning out heritage sour cherries and apples in its ninth decade—and the river itself.

Four species of salmon churn upriver through the summer, along with Dolly Varden, bull trout and other tasty fish. Having journeyed rather far from my near-veganism at the start of this experiment, I caught a pink salmon on my tenth cast—big enough to cost a day’s wages in Vancouver, and up here most of the First Nations fishers won’t even keep them. We ate two overdose meals of fish to keep the meat from spoiling and then, on my second day of fishing, I lost the rod overboard and contemplated karma.

Extreme menus

It’s all a swell adventure, of course—good Boy Scout-variety fun. More important is the fact that much of this ecological wealth is neither ignored nor forgotten in the way that it has come to be in Canada’s urban centres.

Step off the grid a little and local self-reliance is still the rule. In one Hundred-Mile highlight, we rode a bike over back trails to trade canned orchard apples for canned sockeye salmon with a “neighbour” who lives most of his life in the bush—enough so to have a taste for smoked bear’s meat and to know how to make moonshine with berries and potato skins (dry, but with a sweet, homebrew nose). Everyone seems to have a backwoods garden, a mental map of berry patches, an encyclopedic knowledge of smoking techniques.

Well, we weren’t sure how long we’d last in Devil’s Elbow. But then, the blackberries are coming ripe, and the Indian plum, and we just found a bog of blueberries, and the first chanterelles. Already we have pine mushrooms, cans of preserves and salmon, two (successfully) experimental dried berry cakes. We’ll stay a little longer. And when we decide to leave for Vancouver, we’ll go home a little richer.

For more information on finding locally produced food visit the website www.farmfolkcityfolk.ca.