Cedar showcase on Second Beach

If you want to know how much cedar has been used in the construction of the new Qay’llnagaay Heritage Centre on Haida Gwaii, ask CEO Robert Dudoward. Not only can he give you details of the value of the thick posts, the massive planks, the six-sided beams, and the tongue-and-groove siding, but he can lead you to the exact spot the monumental pieces came from.

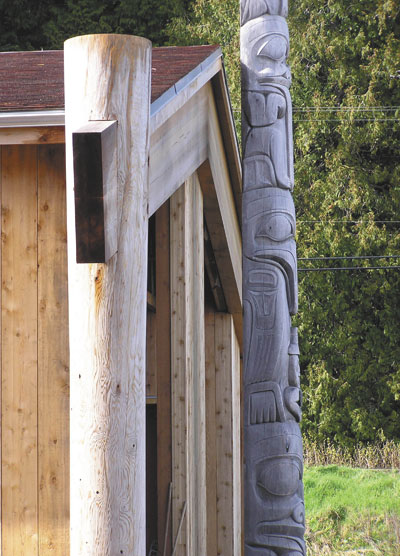

It took one and a half years of scouring the island’s forests to find at least 300 trees to meet the architectural specifications of the buildings at Second Beach, or Sea Lion Town, in Skidegate. But when the centre—a cultural gathering place, museum, tourist attraction, and modern office space in one—opens for sneak previews this summer, visitors will understand why the Haida spent so long looking.

As momentous as the search was, it was a mere fraction of the 40-year dream Skidegate Haida have had to make the heritage centre a reality. In 1994, the planning began in earnest and in 2001 six poles were raised, marking the location of the buildings to come. More than 2000 people feasted with the Haida to celebrate the occasion, and as the centre moves closer to the completion date of summer 2007, more festivities will come.

Cedar is one of the foundations of Haida society, and a core component of the centre. The late Haida artist Bill Reid once wrote, “you can build from the cedar tree the exterior trappings of one of the world’s great cultures.”

He went on to extol the virtues of this diverse wood. “…Huge, some of these cedars, five hundred years of slow growth, towering from their massive bases. The wood is soft, but of a wonderful firmness and, in a good tree, so straight-grained it will split true and clean into forty-foot planks…with scarcely a knot.”

The trouble is, the largest cedars are usually found in valley bottoms. In the past these were easily located, but many have already been logged, and the right to cut in much of the remaining areas rests with large timber corporations. This, combined with strict conservation policies of the Council of the Haida Nation itself, means the monumental trees are becoming harder to access.

Dudoward did much of the ground-searching himself and the wood for the project was finally gathered with a two-tiered approach. Many of the monumentals were cut under free-use permits and a license-to-cut tenure helped offset the cost of some of the dimensional lumber, trusses and joists. Dudoward says there is more than $2 million worth of cedar in the $25 million Qay’llnagaay.

Had the trees not been used in the Haida Heritage Centre, these massive specimens would otherwise be exported off the islands, he says.

“What better place to leave evidence that these trees existed,” he said of the generous use of old-growth cedar in the Centre.

For just one 40-foot plank used for the gable end, they needed to find a tree seven feet in diameter. For a four-foot diameter column, a five-foot tree was found. These dimensions pale in comparison to what the Haida built with in the past, Dudoward says.

Architect David Macintyre said that integrating the 40-year vision of the community into the design was an important process. Inspired by 19th-century panoramic photographs of village sites lined with cedar longhouses and fronted by monumental poles, the space had to accommodate many different uses, like a 45-foot high hall to display totem poles from ancient villages like Skedans, and modern office space. Using local wood and ancient Haida techniques were also important, as was the desire for the buildings to look at home on the site, he said. Hence the stone floors inside and the landscaping with indigenous plants outside.

Although concessions had to be made for today’s building codes, two of the longhouses—the Greeting House and the Performance House—most closely adhere to traditional building techniques.

Slaay Daaw Naay or Greeting House welcomes visitors to Qay’llnagaay. The glass walls and ceiling are contemporary, but the building is based on the traditional six-beam technique. In the end, the timber cruising team never found trees capable of revealing six 57-foot beams, two feet thick and four feet wide; the six 15,000 pound beams were manufactured by laminating smaller boards.

In Gina Daawhlgahl Naay, or Trading House, visitors will find exhibits highlighting the history of trade between the Haida and their neighbours. Present-day trade items include a selection of souvenirs, books, local art and more. Ga Taa Naay, or Eating House, will feature exhibits on gathering and preparation of traditional foods, and a café serving Haida specialties.

Gina Guuahl Juunaay (Performance House) is built with two parallel round beams set on pairs of uprights. Traditionally, these 52-inch beams would be cedar, but Dudoward had to go with spruce instead.

The beams, like most of the other locally-sourced wood, was transformed by master sawyer Arthur Pearson at a small mill set up in Skidegate. He and his team created 88 monumental pieces for Qay’llnagaay on a Peterson swivel mill with a 21-inch swinging blade and some unique modifications. When underway the sawyers can run a 72-foot cut.

The biggest challenge, Pearson says, was building the metal jigs to help guide the enormous cuts.

But he is proudest of the lathe. This contraption helps him rotate a 42-inch diameter log and peel it into a 36-inch diameter column. “People are amazed at what we’re doing,” he said. “They stop and watch, especially when we’re turning the lathe.” Pearson and his team started work in November 2004 and were still finishing the last few pieces in April 2006.

Besides the incredible wood features, the centre incorporates other sustainable design techniques. The flat-roofed structures all have “green roofs,” Macintyre explains. These are seeded with low-growing plants that absorb some of the buckets of rainwater this coastal site receives.

A geothermal system is buried in the large parking area, and black coils flow with water used to cool or heat the buildings depending on the above-ground temperature.

Dudoward thinks the focal point will be the open-air carving shed, where visitors can meet the artists working on more monumental projects and be warmed by the great stone fireplace.

What will they be carving? Cedar probably. The wood is so ubiquitous not only in Haida buildings, but in art, clothing, music and household items, that local artist Giitxsaa was surprised at how much of another material is found at Qay’llnagaay. “There’s a lot of glass,” he says with a wry smile.

His cedar pole representing the ancient village of T’aanuu is front and centre on the beach at Seal Town, one of six monumental poles representing the southern Haida. He took on two inexperienced carvers to assist him in the project. The power of his guidance can be seen most noticeably in the shark-woman face depicted by first-time carver Victoria Moody.

Giitxsaa attended the Vancouver School of Art, and went to Victoria to learn the basics of carving totem poles in the late 1960s. Now that he is back home on Haida Gwaii and a school of art and design is set to open at Qay’llnagaay, there may be more who will learn the skill from him.