Hunting guide tells all:

In more than 20 years of leading trophy hunters to the big game of BC’s northwest, Bob Henderson has faced more than one close call, including charging grizzlies, his plummeting float plane, frostbite and hypothermia. But it wasn’t a life-threatening event that heralded the end of his career as a trophy-hunting guide. It was the bewilderment he felt after hearing an angry client’s rant.

Wanted: more buck for the bang

It was 1985, and he and two hunting clients had sighted two caribou bulls in Paradise Basin, an alpine area above Tatlalui Lake. Because the animals did not meet legal requirements, shooting them was out of the question. So the three men simply watched, from about 30 metres away, while the two bulls locked horns in combat for some 45 minutes.

“I remember thinking how I would have loved for my kids to see this ageless, alpine drama unfolding before us,” recalls Henderson, in his newly published autobiography, In the Land of the Red Goat.

Moments like these have fueled his love of northwestern BC wilderness since his first glimpse of it at age 18. They explain his view that hunting delivers a more intimate, intense experience of nature than some gentler outdoor pursuits, such as hiking, because it forces people to slow down, be very still for hours, smell, observe and attain a kind of invisibility in the landscape.

Henderson’s bush instincts, honed over decades, had served him well. But on that day, a mistaken assumption caught him off guard: he’d thought his wonder was shared. That’s why Henderson was utterly dumbfounded when one of the clients, furious, declared that he wasn’t paying for a natural history lesson, but for an animal that was legal to shoot—and the sooner the better.

“I began to wonder if I was losing perspective,” writes Henderson. “Maybe he was right. Most hunters probably do want to go home with a full bag and aren’t really interested in the peripheral aspects of the hunt.”

Henderson knew well that the world was more frenetic, and the industry more competitive, than in the early 1960s when he began to work for the first licensed guiding outfit in the region: Walker Frontier Services. By the mid-80s, trophy-hunting clients, described by Henderson as typically “alpha males,” expected the same results—an impressive, accessible, legal target—from a 10-day hunt as from the 28-day hunts that were formerly the norm. And the five-figure sums paid to trophy hunt in northwestern BC can as easily buy hunting expeditions in Chile or Argentina.

Anecdotes like these round out Henderson’s book, which is the latest publication of Creekstone Press, a Smithers-based publisher which specializes in northwestern BC talent and history.

Climbing the charts

Lynn Shervill, who co-owns Creekstone with his wife Sheila Peters, explains why Henderson’s life story caught their eye.

“Bob Henderson is a storyteller that exemplifies the oral tradition. Until recently he’d never written these things down, but over the years of telling these stories repeatedly, they still contain an astonishing amount of detail… detail which squares with the memories of other people who were there,” says Shervill. “We knew these stories had to be recorded and shared more broadly, and that Bob had to be the one to do it.”

Creekstone is celebrating the fact that Red Goat has recently become their fourth title to crack BC’s top-10 best-seller lists—and it’s not surprising. In the Land of the Red Goat offers a compelling account of an adventurous life and a valuable contribution to local history.

Job hazards

The book opens with Henderson’s introduction to northwestern BC wilderness as a freshly graduated 18-year-old, a product (by his own description) of the “smug, comfortable atmosphere” of the “right schools and social clubs” in BC and Ontario. He’d accepted a job offer from guide-outfitter Tommy Walker, and with his first view of the Spatsizi from the bush plane which flew him to Walker’s base camp at Cold Fish Lake, he was hooked.

Although Henderson went on to complete a degree, obtain his pilot’s license and do a stint in radio broadcasting in the off-seasons, he could never get back to the bush fast enough.

That’s where he honed his fishing, wrangling and flying skills, and guided trophy hunters—many of whom ranked among the North America’s corporate elite—to the Spatsizi’s moose, goat, Stone’s sheep, grizzly, black bear, and caribou.

Henderson left Walker’s employ in 1968 and went on to guide in the equally remote Tatlatui with Love Brothers & Lee, eventually becoming a partner. He became executive director of the BC Guides Association and helped found the Spatsizi Biological Research Centre, a team of professionals which monitored wolf and caribou populations.

Along the way, Henderson found himself evading grizzlies, crash-landing bush planes, fighting forest-fires, driving a five-ton snow machine on the crumbling ice of the Stikine River, retrieving the remains of colleagues from a fatal plane crash, embroiled unwittingly in a mine labour dispute, and grappling with high-profile public controversy around wildlife counts.

Fair chase considered

In the Land of the Red Goat also offers a fascinating insider’s perspective on BC’s multi-million dollar trophy-hunting industry, which directly employs more than 2,000 people and caters mostly to American visitors. This elite pursuit is increasingly immersed in emotionally charged ethical debates—about humans’ motives for killing animals, how “fair chase” is distinguished from wanton slaughter, who should monitor and address wildlife population health, and whether human relationships with the animal world ought to be measured by actions toward individual animals or towards entire species and ecosystems.

Speaking with Northword at his Tyee Lake home, it’s clear that Henderson has considered these questions and made peace with his answers.

Trophy-hunting, says Henderson, stems from a primeval human need to demonstrate prowess to one’s social group by bringing home the biggest and best provisions. “Everyone has some desire to hunt, but it manifests itself differently in each person,” he theorizes. “Some people can satisfy that desire by fishing, or simply viewing wildlife.”

For Henderson, it’s all about the pleasure of the chase. He proudly subscribes to the widely promoted hunter’s ethic of “fair chase”: offer your prey a fighting chance by foregoing illegal practices like baiting and technologies such as radios, helicopters and other aircraft, automatic weapons and snowmobiles. It’s why his favorite animals to hunt are Stone’s sheep, which inhabit the most challenging terrain.

“Killing is actually anti-climactic,” says Henderson.

In fact, the mule deer whose mounted head presides over Henderson’s lakefront living room is the only animal he’s ever set out to shoot. He doesn’t count the grizzly that charged him during his first summer in the bush (which he killed in self-preservation), or the times he’s “finished off” animals wounded by clients. Ethical guides do this as necessary, he explains, but are legally forbidden to hunt animals for their clients.

Of course, “there has always been a segment of people in that sport, as in any other, that wants to cheat.” In one incident described in Red Goat, a tired, well-heeled client offered a hefty chunk of cash to Walker Frontier Services staff to shoot a bear for him. No one even dignified the illegal proposal with a response. “It was as if that hunter had broken wind in church,” writes Henderson.

Mixed feelings

Of course, ethics codes are not the same as laws. And Henderson has mixed feelings about some BC laws—especially those crafted by faraway bureaucrats and politicians with little stake in, or experience of, the ecosystems they manage.

For example, BC law requires hunters to pack out all edible portions of killed animals (except grizzlies and wolves, which aren’t considered edible), to encourage proper use of hunted animals. “Emotionally speaking, this makes sense,” concedes Henderson. “Biologically, it doesn’t.”

While some meat is eaten by hunters or distributed among locals and food banks, he explains, much of it ends up in the dump. European hunters can’t take it home, and some meat, like caribou in rut, is refused even by dogs. “If left behind, this meat would feed marten, eagles, wolverines, bears and other carnivores.”

He believes he is typical of many guides, who start out with a dream of a pure, wilderness-based lifestyle, but end up beaten down by endless paperwork and conflicting directives from government.

“In my 40 years of guiding, I’ve encountered Parks staff perhaps 10 times out there,” he says. “Decisions are being made without any real understanding of what’s involved.”

For example, in recent years government has encouraged trophy-hunting guides to diversify into other wildlife-related businesses. Henderson did just that: after leaving the trophy-hunting business in1986, he secured permits and agreements to build a lodge on beautiful Tatlalui Lake, which now serves as the base for his guided fishing and wildlife-viewing trips.

But that business is now imperiled by a BC government decision to approve, despite sustained protest by Henderson, a license for his former business partners to site an additional trophy-hunting camp five kilometres down the lake.

“I can’t book guests to come view wildlife if there’s any possibility that another business will be killing moose on the lakeshore,” he says. He expects the government’s new emphasis on recovering costs through commercialization of BC parks will increase such land-use conflicts.

Industrial development, such as mining and power production, creates new pressures. Although he recognizes jobs and revenue are important, Henderson is loathe to see Northgate’s planned power project destroy Cascadera Falls, whose beauty he believes trumps all economic values, or its Kemess Mines expansion which will turn Duncan Lake into a tailings pond.

“No lake should be used as a tailings pond,” he says, invoking the possibility of contamination of area water sources if the tailings are not properly contained. “Duncan Lake is the headwaters of the longest river system in North America.”

The real debate

Certainly, decades of guiding profoundly rearranged Henderson’s orientation towards the natural world. “When I first came, I looked at [this region as] a frontier, as something that needed to be conquered,” he relates. “This resulted from my school training… ours was a generation that had just gone through World War II. It was viewed as quite alright to blow everything up.

“Now I realize the wilderness is not a frontier at all. It’s something you need to learn to adapt to.”

Close working relationships with First Nations also changed his world-view.

“Tommy Walker felt that the native population was the white man’s burden,” he remembers. “If anything, it was the other way around.”

Centuries before Tommy Walker set up Walker Frontier Services, the Spatsizi had been home to several First Nations, including the Tahltan, Tlogot’ine, and Casca Dene. (Spatsizi, in fact, is a Tahltan word meaning “red goat”, referring to mountain goats which rolled in red dust near Cold Fish Lake.)

They’d developed a vast trail network to facilitate hunting, food gathering, and trade with other First Nations (including the Nisga’a, Tlingit and Gitxsan). From the 1860s and well into the 1930s, they had sold guiding services to trophy hunters.

But settler-borne diseases such as smallpox devastated First Nations communities here, as elsewhere in BC, in the 1920s. And during World War II, guiding business nose-dived.

This was why more than 100 Tlogot’ine people returned to their traditional gathering site at Cold Fish Lake—where Tommy Walker was developing his new guiding business. He had successfully acquired from the BC government the first exclusive license to guide in almost 6,500 square kilometres of their traditional territory.

“[The Tlogot’ine] were displaced by the licensing system,” says Henderson.

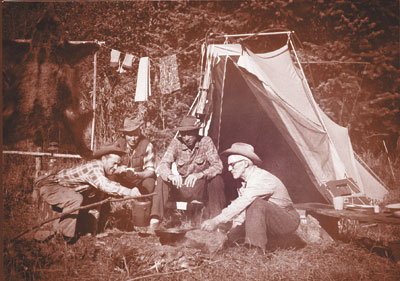

Several Tlogot’ine found employment with Walker Frontier Services. Although housed separately from white staff, their local knowledge proved vital to the British-born Walker. Henderson fondly remembers the all-native crew he worked with during his first year.

“I didn’t realize it at the time but the chance to join such an august group of men, even as a helper, was a fabulous opportunity… these men were truly the all-stars of professional guiding.”

But the rest of the Tlogot’ine, camped nearby, weren’t so welcome. Henderson writes:

“Suggesting the group was starving, [Walker] asked the Indian agent at Telegraph Creek to remove those people who were excess to his needs. The agent used this as an excuse to relocate them all to Telegraph Creek [some 240 kilometres away], ignoring the friction that existed between the Tlogot’ine and the Tahltan as a result of ancient boundary disputes.”

“Centuries of protocol had been destroyed with the stroke of a pen, by someone who had no real understanding of these people, for administrative convenience,” Henderson remembers.

Before he steps outside into the cool autumn sunlight, he reflects on the challenges he’s grappled with as a guide.

“It’s what the whole debate in northern BC is all about. If we’re going to take advantage of all these resources, how do we do it without changing attributes of landscape, and the society there prior to it?”

Find out more

Bob Henderson’s Tatlatui Lodge www.tatlatui.ca

Creekstone Press

www.creekstonepress.ca

A CBC TV report, broadcast in Nov. 1981, about Spatsizi guide-outfitters’ stand-off with Greenpeace protestors, including Patrick Moore

http://archives.cbc.ca/IDCC-1-69-867-5037/life_society/greenpeace/

BC government resort strategy

http://www.tsa.gov.bc.ca/resorts_rec/resorts/index.htm

Code of Ethics for the BC Guide Outfitters Association

http://70.69.57.209:1280/GOABC/html/02standards.htm

Another view of trophy-hunting

http://www.raincoastfoundation.org/proj-grizzlies/buyout-dec2005.htm

© Larissa Ardis 2006