Fifty-Four Forty or Fight: How a U.S. border crossing almost wound up in the Bulkley Valley

I’m sitting on Hubert Hill, a small forested prominence by Highway 16, about 15 minutes south of Smithers, between Round Lake and Woodmere Roads. Here in the soft light of early summer, I can look across the highway and the Bulkley River to the Telkwa Mountains. Below me, the busy US border crossing has cars backed up on either side waiting to come through the gates, be photographed, have passports checked, the occasional car searched. It’s another day on the international border, just south of Telkwa, BC.

Well, not really. Bulkley Valley residents know that the continental US is nowhere near our remote and quiet home. Unlike the majority of Canadians, who live with 100 km of the US border, we in northern BC face a 14-hour drive just to get to that long, straight international border that runs from Washington State to Minnesota, the 49th parallel.

But it might not have been so. For here on Hubert Hill I am sitting on 54° 40’ N.

A Bit Of History In the year 1844 Texas was its own country, Mexico owned California, and there was intense debate in the US about territorial expansion. It was an election year, and Democrats believed that the country had the right to expand to the Pacific. Beyond the Rockies, in the Northwest, was the alluring Oregon Country, an expanse of mountains and rivers jointly occupied with the British. It encompassed everything north of California as far as the arctic.

Democrats who supported slavery were for vigorous expansion in the south, where new states would be likely to support slavery. They hoped for the annexation of Texas and the acquisition, by force if necessary, of Mexico’s provinces of Nuevo Mexico and Alta California (today’s New Mexico, Arizona and California). Anti-slavery Democrats, in contrast, wanted northern expansion, into areas unlikely to support slavery. For them the Oregon Territory looked like an opportunity to tip the balance of US states, and it was they who would later coin the phrase “54-40 or Fight!”

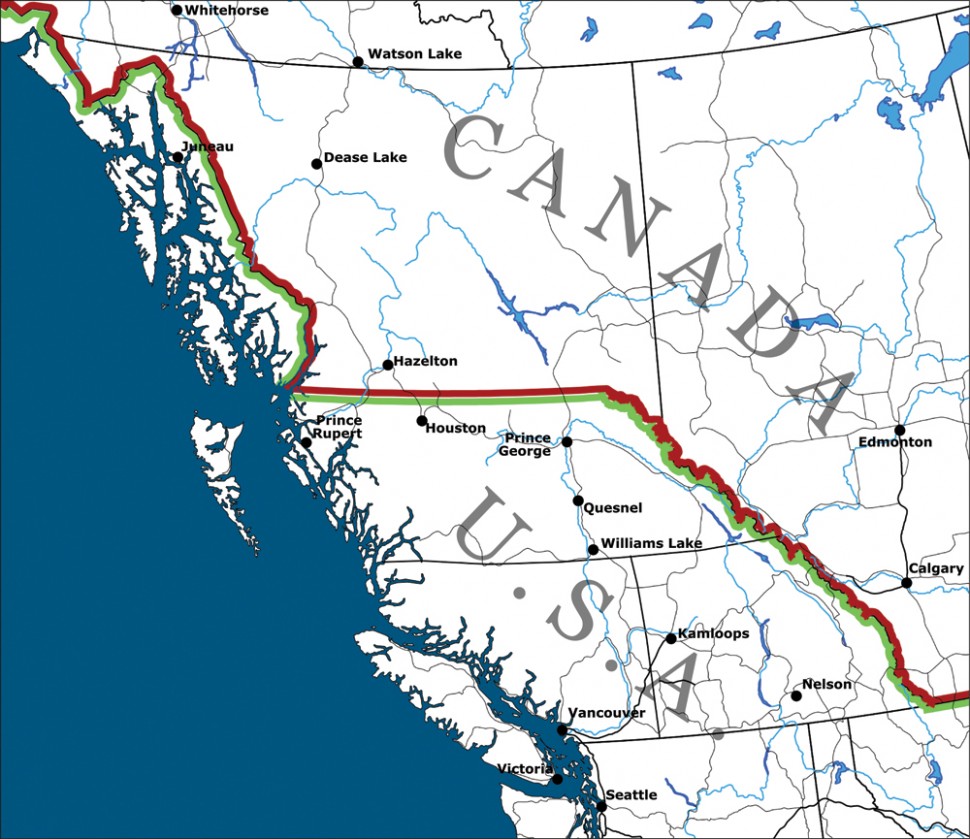

Fifty-four Forty or Fight meant that in negotiations with Britain over how to divide the Oregon Territory, the United States wanted—and was prepared to fight for—all the land up to a line of latitude at 54° 40’. This would afford enough room for five or six new states, the northernmost of which would end just south of what is today Telkwa. Not that anyone in Washington or London had much idea of what was up here. The key feature of the Oregon Territory, which the Hudson’s Bay Company called its Columbia Department, had always been the Columbia River, widely seen as the best way to get furs out of the region. But the Columbia went no further north than about the latitude of today’s Williams Lake. North and west of it the geography was little known back in England or Washington DC.

Back in the US, the Democrat James Polk, a southerner and slave-owner, won the election and set his sights on acquiring Texas. After he sent troops there and offered Mexico millions of dollars for its possessions, disgruntled northerners coined the phrase “Fifty-four Forty or Fight!” to try to get northern expansion back on the agenda. But in April 1846 there was an unfortunate (and timely, from Polk’s point of view) incident in which a Mexican force fired on a US patrol in Texas. The US declared war on Mexico by July. When the Mexican-American War was over in 1848, Mexico had ceded to the US what we know today as New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Nevada and California.

The war was extremely unpopular with northern abolitionists. This is the war that caused Henry David Thoreau to refuse to pay his taxes, to get thrown in jail, and to write Civil Disobedience. With all of this going on, Polk was keen to settle the Oregon question and keep the anti-slavery Democrats from initiating some kind of conflict with Britain. So in April 1846 (a mere two days before the clash in Texas that provided an excuse to start the war) he proposed to Britain a treaty to divide Oregon. Polk was easy: he wasn’t going to fight for 54° 40’. Instead, he proposed, how about we draw the line at 49°?

Britain accepted, and in July the two countries concluded the Treaty of Washington, also known as the Oregon Treaty, dividing the Oregon Territory at 49 degrees north, precisely where the US-Canada border runs today. The Americans continued to call their piece the Oregon Territory; after some time the other piece came to be known as British Columbia.

A Different World But could it have happened otherwise? Could the anti-slavery faction in the US have carried the day? Could they have ignored Texas and California and focused all their energies on acquiring the territory up to 54° 40’?

Britain was not keen to fight. The northern part of the Oregon Territory produced furs for the Hudson’s Bay Company, but it represented little else. There were no settlements like the Americans had made in southern Orgeon – and increasingly the HBC was shutting down its posts on land and was operating instead from a steamship that cruised the coast. Gold would not be discovered on the Fraser for some ten more years. As well, the government in London was embroiled in a domestic crisis over food supplies, and needed to maintain good relations with one of its chief grain suppliers, the United States.. It is quite possible that Britain would have settled for giving the US all of Oregon.

And our world would indeed be different. The central feature of our northern British Columbia is Highway 16. It links many of the communities in northern BC, but its route was dictated by that of the earlier Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad (today’s CN). This rail line, built between 1911 and 1913, was responsible for the creation of several towns along Highway 16, and it boosted the fortunes of those that were already there. And most of it lies south of 54° 40’.

In short, northern BC’s most significant transport corridor wouldn’t even be in Canada. The familiar townsites of McBride, Prince George, Vanderhoof, Fort St. James, Burns Lake, Houston, Terrace and Prince Rupert—all of these would be in the United States. Only Telkwa, Moricetown and Hazelton would remain north of 54° 40’. Smithers, a child of the railway, would not exist.

If Britain did not retain any of the Columbia basin in 1846, this province north of 54° 40’ would not likely be called British Columbia. With the gold discoveries along the Fraser and at Barkerville being in the US, would Canada even have made an effort to get this far-flung northwest area to be part of Confederation?

Back On The Border So you can picture it here, just south of Woodmere Nursery, how the extra-wide shoulders of the American road give way to the more moderate Canadian road width. The highway pullout/rest stop, the one with the beautiful view of the Bulkley, is just north of the border. It’s a convenient spot to stop and get your passport out.

The next time you drive past that pullout, think about how an international border almost wound up here. Marvel at how you can just drive between Telkwa and Quick without thinking about it, without making sure you have your travel documents, without making sure you’re not carrying any fresh meats and fruits. And consider the uncomfortable fact that, but for the American appetite for slavery, it might all have come out differently.

Yeah!

U.S.A never forgets 54-40 parallel north. It was the first U.S. Captain Robert Gray that found Oregon Country in 1790 until British got half land in 1846.

Somehow, Britons stole his map then they claimed the land.

👤 Ron 🕔 Jan 25, 2015

Interesting article; right up to the last sentence where the author takes a flying leap into bigotry and ignorance with, “American appetite for slavery.”

If anyone wants a concise summary of slavery, historical and American, research history is everywhere; but here is a simple start, <http://townhall.com/columnists/michaelmedved/2007/09/26/six_inconvenient_truths_about_the_us_and_slavery/page/full>

👤 Robert Walther 🕔 Aug 02, 2015