Skeena Forks—The history of Hazelton

In the early 1800s, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was having difficulty breaking into the long-existing First Nations trade routes through northern BC, especially the trails and seasonal trade patterns between the Nass River and Babine Lake. The company was looking for a way to increase its presence in the North and get in on the profitable trade of furs and fish.

It was Simon McGillivray who, in a letter to George Simpson in July of 1833, advocated that the HBC establish a post at the confluence of the Skeena and Bulkley rivers and get supplies there by navigating the Skeena from the coast. McGillivray had been sent to look for ways to improve trade to and from the coast and was told by his First Nations guides that, from where they stood at the confluence of the Bulkley and Skeena Rivers, a canoe could reach the Pacific in a few days.

That was June, 1833. But it wasn’t until 1866 that the Hudson’s Bay Company sent two men who were already in the Skeena area, Thomas Hankin and William Manson, to establish a small post at Skeena Forks, assess local trade routes, and take advantage of selling goods to the gold-seekers and telegraph construction crews that were increasingly travelling through the area.

But in 1868, just two years after opening, the small HBC post at Hazelton was closed with the company claiming that it hadn’t brought in a significant enough profit. Pioneer Hankin must have sensed a business opportunity because he left the HBC with the closure of the Hazelton Post and decided to stay on in the area. Hankin teamed up with Robert Cunningham and together they opened their own store and liquor dispensary near Gitanmaax. He no doubt saw that the Skeena Forks was becoming a frequent stopping place for travellers all months of the year—surveyors, miners, and their pack animals. This was also when the Collins Overland Telegraph project was abandoned and some of those men stayed and built cabins in Hazelton. With their pioneering store Cunningham and Hankin attempted to supply the travelling prospectors and occasional settler with some goods brought up the Skeena by freight canoes in summer or dog teams in winter.

Clearing the way

The trails connecting the newly established Hazelton community with the Babine and Omenica district and the Nass and the Coastal District were well travelled, but not convenient for pack animals. Dr. R. G. Large writes, in his book The Skeena: River of Destiny, that in 1871 Cunningham and Hankin were contracted by the provincial government to improve the trail between Gitanmaax and Babine Lake—originally a First Nations trail in use for centuries, if not millennia, and more recently the route of miners heading to the interior. Prospectors had complained about the narrow path and the numerous fallen trees blocking it. Many became weary clearing the trail for their pack animals; some who were ill-prepared for the difficult work became disheartened and abandoned the trip. A few naive travellers even lost their lives. A crew of men worked on improving the trail, completing it just in time for the Skeena gold rush of 1871 and 1872.

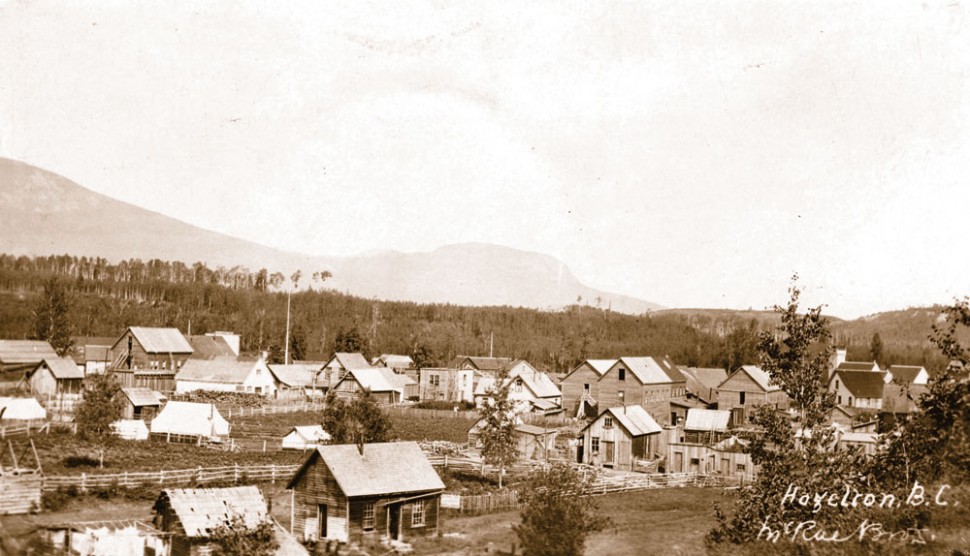

“In 1871,” writes Large, “there were six buildings and a tent in Hazelton.” But more stores were soon constructed and permanent homes went up amongst the temporary shacks. In Victoria’s British Colonist in March, 1872, an ad for the Farron and Mitchell Store at Skeena Forks boasts, “Miners and others bound for the Omenica will find groceries, provisions and complete outfits at our store. Having 20,000 pounds of bacon already at the forks, we can sell it cheaper than it can be brought in from Victoria.”

A letter from “Hazelnut” appeared in the newspaper the same year. The anonymous writer describes Hazelton as a town “situated on the west bank of the Skeena about one mile from the forks of the Wetsenquor [Bulkley River], on a large level hazel flat from which it has taken its name.” Hazelnut goes on to say that there were now 10 large, well-built stores and houses beside small dwellings. The writer also says that “our gardens look splendid, and not less than 20 tons of potatoes and at least 10 tons of turnips, besides other vegetables, will be the result.”

The Hudson’s Bay Company saw the successes of Cunningham and Hankin—not only could supplies get to the forks of the Skeena but there were people there to buy them—and decided in 1880 to reopen its post.

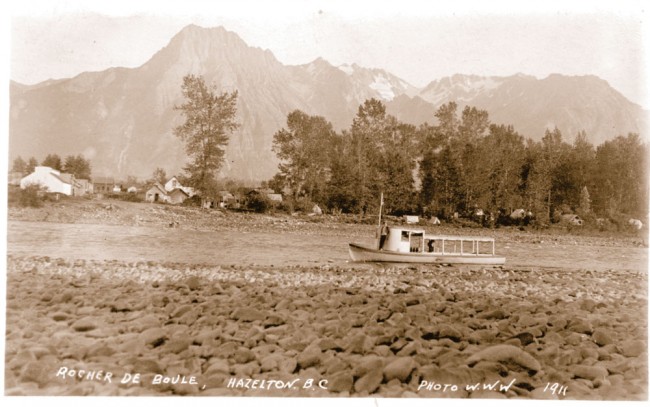

Sternwheelers arrive

A Skeena River survey was carried out in 1890 for the HBC. The surveyor, Captain George Odin, recommended navigating the Skeena with sternwheelers. In 1891, the sternwheeler Caledonia was built and made the first successful trip upriver to Hazelton. The steamboat era changed Hazelton; the settlement became permanent and flourished. “It was a vital centre of activity for prospectors, traders, merchants, pack-train operators and missionaries,” states a display at the Hazelton Pioneer Museum. The Skeena may have been difficult to navigate by sternwheeler, but the new mode of transportation meant more freight and more passengers arriving in Hazelton.

One of the many new settlers to Hazelton was F. C. Chettleburgh. In a 1962 recorded interview, he recalls his 1909 journey up the Skeena to Hazelton aboard the sternwheeler Port Simpson, during which he was “raptured” by the towering mountains, the hardy settlers and the First Nations people. “In those days, Hazelton had about 50 or 60 whites and an equal number, if not more, of Indians living up on the bench. And the Indian dogs—there must have been 150, if not more, living under the sidewalks near the cafés and the hotels.” Chettleburgh lists off various businesses of early Hazelton, including three hotels, the Hudson’s Bay Company, Sargeant’s store, Larkworthy’s store, a jeweller, a watchmaker, a photographic shop, a bank, the newspaper and the hospital.

According to the Hazelton Pioneer Museum and Archives, between 1890 and 1915 Hazelton was the largest community in northwestern BC. Chettleburgh summarizes these years and the people who lived in Hazelton (1909), and later in early Telkwa, saying, “What made that country—and when I say that country I mean the Bulkley Valley, the Omenica—more than anything else, in spite of the fact many that came up were very green—was as long as they played ball, and did the right thing, and paid up their debts, they were always brothers. They always helped one another out. And that’s the remarkable thing about that country, how they stood behind one another. It helped to build up the character in the young fellas and those that couldn’t take the rough spots they naturally had to get out.”

The little community on the banks of the Skeena grew from Simon McGillivray’s first imagined trading post in 1833 to a bustling permanent community by 1890, and remains today a permanent community of very proud locals.