Photo Credit: Facundo Gastiazoro

Colouring the Map

Colouring the Map

by Jo Boxwell

Heading south from Whitehorse across the Yukon-BC border, the highway cuts through waves of yellows and oranges as the deciduous trees offer up their last bursts of colour. The September breeze carries a warning chill; fall comes early this far north.

We’ve only just entered northern BC, but we won’t remain in the province, or the country, for long. We’re heading into Alaska via the Coast Mountains, and the White Pass will be our crossing point. Trees shrink to the size of shrubs, dwarfed by the harshness of the climate. There’s no snow yet, but the grey rock, narrow lakes, and low-lying fog are muted compared to the colours along the road that brought us here. The weather has shaped this region in ways that make it unfamiliar and fascinating.

We pull over to take in the landscape, and a tour bus parks behind us. We aren’t far from the cruise ship port of Skagway; travellers are not an uncommon sight here.

A handful of tourists walk a short distance over the tough shrubs and hobbled trees towards a lake. I follow with my camera, curious to hear what their guide has to say about this inhospitable land. The White Pass, I learn, was not named for the masses of snow that accumulate here during the winter months, but after a Canadian politician, Thomas White, who was Minister of the Interior when the route was first trodden by prospectors in the late 1880s. I admit being a little disappointed to discover that this impressive stretch of land was not named for the forces that shaped it.

When the Klondike gold rush surged through the White Pass, it became a gruesome place. An estimated 3,000 horses were driven to exhaustion and succumbed to the harsh environment. The pass acquired another name: “The Dead Horse Trail.”

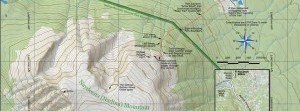

Northern BC is speckled with dots on the map, great and small, whose names reference colour. The origins of some appear to have been lost, and others may ultimately disappoint, like Fraser Fort George’s surprisingly unremarkable Emerald Lake, but many of these names capture fragments of the history, culture, and natural beauty of our region.

Blue River The community of Blue River and its namesake in the North Thompson Valley may be the most well-known Blue Rivers in BC, but northern BC has its own: a Dease River tributary close to the BC-Yukon border. The Blue/Dease Rivers Ecological Reserve protects wetlands and forest habitats.

Kwadacha River The Sekani people of the area weren’t referring to rapids when they named this river the Kwadacha, meaning “white water,” in the Tsek’ene language. Glacial erosion of bedrock generates rock flour, and the high concentrations of rock flour flowing into this river give it a cloudy colour. Kwadacha is now also the name of the First Nation community formerly known as Fort Ware.

Pink Mountain North of Fort St. John, the mountain is named after the pink hue in the rock, and is renowned for Arctic butterfly viewing. Traditionally used by the Halfway River and Prophet River First Nations, part of the mountain is now protected by the Pink Mountain Provincial Park. The area is home to diverse flora and fauna, including a plains bison population introduced to the area by a local outfitter in the 1960s.

Tête Jaune Cache Pierre Hatsinaton was an Iroquois-Métis fur trader and trapper who guided French voyageurs into the region that bears his nickname today. The French called him Tête Jaune (“yellow head”) because of his blonde hair. The Yellowhead Highway and the Yellowhead Pass were named after him. The little community of Tête Jaune Cache came to bear the same name because Pierre was said to have stored a cache of furs there. The community briefly experienced boomtown status (population 3,000) during the construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific railroad.

Red Rock Located on the traditional territory of the Lheidli T’enneh, this community got its name from the Fraser Canyon’s reddish hue. Presumably thanks to a good-natured local resident, there is a painted red rock on the side of the highway for those disappointed by the absence of any red rock among the trees visible from the road. Following the gold rush that built Barkerville, Red Rock attracted gold miners staking small claims along the Fraser River, and later railway workers as the Grand Trunk Pacific crept closer to Fort George. More recent inhabitants include farmers and former employees of a forest research nursery, which closed in 2000.

Blackwater River The origin of the name “Blackwater” is said to be a translation of the Indigenous name that referenced its colour characteristics. The riverbed is darkened by tributaries that pass through muskeg and swamps, giving the river its murky tones. As it passes below Tsacha Lake, the Blackwater also cuts through black volcanic rock, leaving behind impressive canyons and rapids. The Blackwater River is a designated British Columbia Heritage River, and was a significant trade route between the Dakelh and coastal nations. The Grease Trail, so-called because of the eulachon fish oil commonly traded by the coastal nations, ran parallel to the river (predominantly on the north side). This was also the route that Alexander Mackenzie was guided through to reach the Pacific Ocean in 1793. Mackenzie referred to the river by another name that is also still in use: West Road. Today, with excellent trout fishing but limited access, the river attracts adventurous fly-fishing enthusiasts.

White Swan Park Welcome to Fraser Lake, the “White Swan Capital of the World.” Every November, on the traditional territory of the Stellat’en First Nation, over 1000 trumpeter swans arrive at the lake as part of their migration journey. Hunted almost to extinction in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these distinctive white birds have made a comeback due to reintroduction efforts. Fraser Lake is also a popular spot for other migrating waterfowl. White Swan Park is a day-use facility and municipal campground.

Red Rock Mountain At the northwest end of Fraser Lake, the trails leading up Red Rock Mountain offer access to an extinct volcano and ancient lava flows. The Stellat’en name for Red Rock Mountain is Tselk’un. This is a sacred area, and visitors wishing to hike the trails must request permission from the Stellat’en Band Office.

Red Bluff Provincial Park Rugged cliffs stained by the iron content in the rock give this provincial park its name. The cliffs’ dramatic descent into the water make it a popular spot to paddle around or walk on the self-guided interpretive trail. The park is located on Babine Lake, BC’s longest natural freshwater lake.

Rainbow Range The Rainbow Range is known as Tsitsutl in the local dialect, meaning “Painted Mountains.” The range is an eight million-year-old shield volcano, and its rich minerals produce striking waves of yellows, reds, oranges, and lavenders in the lava rock. Nuxalk and Dakelh First Nations have inhabited this area for thousands of years, and the ancient grease trails that were vital trading routes still exist today, including the 300 km Mackenzie Heritage/Grease Trail.

Located in Tweedsmuir Provincial Park on the Chilcotin Plateau, there is another reference to colour within the plateau’s name: Chilcotin is an Anglicized version of Tsilhqot’in and the Tsilhqot’in are the “people of the red ochre river.”

Skidegate Named after a hereditary Haida chief, “Skit-ei-get”, means “red paint stone.” Today, the community is a Haida village home to the impressive Haida Gwaii Museum and the Haida Heritage Centre.

Maroon Mountain North of Terrace, this hiking trail exists at least as far back as the mining exploration of the area. As well as scenic views of the surrounding ranges, hikers will come across the rusty remnants of old mining claims.

Red Rose Peak Located in the Rocher Deboule range, this area is best known for the now defunct Red Rose Mine, which operated between 1941 and 1954. Tungsten, copper, gold, and silver were mined from the area, and the remains of the mine buildings are still present.

Rainbow Alley Provincial Park Unlike the Rainbow Range, this park was named for the water, not the rock. The area is known for world-class rainbow trout fishing. The park stretches between Nilkitkwa Lake and Babine Lake. Part of the traditional territory of the Ned’u’ten, the area is still used for fishing and trapping.