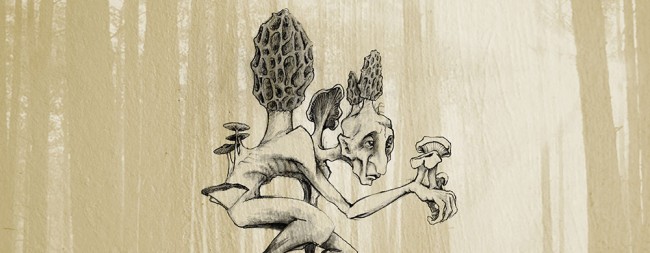

Photo Credit: Facundo Gastiazoro

Life in Dead Places

Morels like dead places. Brains on the outside. Greyish honeycombs on stems. That’s what we have in common. We aren’t pretty and we thrive in dead places.

I hunt them, the morels, following the ruins of forest fires and decaying trees. I slice through their thick cores and throw them in my backpack. My bones ache from age and lack of sleep and being out of place. Out of shape. I was never much of an outdoorsman. Not like my dad. I never took to carrying a rifle. Stalking animals. Tracking them as they stumbled, dying, because the shot wasn’t clean. He taught me a few things though, about being out here. Convinced me that fresh air was good for me.

Mosquitoes swarm. Only the females bite, sucking in blood to make babies. Itchy swellings burst through the hair on my arms. A red-cheeked woodpecker pulls bugs out of bark. That’s what we’re all occupied with; eating. Other birds call to each other in the trees. What are they saying? They are warning each other; here comes one who eats.

Morels can’t be commercially produced like other mushrooms. Their desires cannot be easily predicted. They are discreet. Particular. A delicacy, cooked in butter and served to rich people and those who aspire to be; those who will seize any opportunity to consume each other.

It was a small fire, quickly extinguished. Not large enough to attract the commercial pickers. I blacken my fingers with the ash and collect only a few. The charred earth ends abruptly and I forge a path between decaying trees felled by the pine beetle.

Dead places aren’t really. They are crammed with lives that others have no desire to see. Breaths are quieter, smaller there. Nobody hears the maggots’ mouths crunching and slapping. Nobody watches the rot grow. The smell of rot is curious, isn’t it? It’s the smell of all the dirt inside of us slowly being released. It sickens them. Those who fear us. They do what they can to stamp us out, we who live in dead places.

“Bit dingy in here, isn’t it?”

She was mild with middle-aged roundness. No expression on her face. She’d tucked it in, with her large blouse. She whipped open the mothballed curtains. Dust struggled and the walls shuddered with the brightness, or the passing freight train.

“It’s cooler with the curtains closed,” I explained, though it wasn’t hot outside. I leant against the doorframe, trying to give her space, attempting to look relaxed as she passed judgement. Her nose twitched with the smells I had become accustomed to.

“Do you let your guests smoke in here?” she asked.

“No.”

“Where are the stickers?”

She’d lost me.

“The no smoking stickers.”

It used to be simpler. Her type used to smoke. She took a moment to scribble on her clipboard. I looked out of the window into the parking lot. A couple of old bangers and a beast of a truck. Hers; polished, new.

Last night I camped on the hard ground and the cool air chilled me. Not as hard as lying on concrete. Not as cold as bodies on public transit, but I miss the city. I didn’t choose to leave it. It devoured me; she did. The inspector, with her heels clackety-clack and her smartphone rumbles.

I’ll admit it wasn’t the Ritz. That’s why it said “motel” out front. It wasn’t pretty, but there was a need for it. Sort of like a public service. Most folks could afford our rates if they needed to get away. Maybe for a night. Sometimes for a week, or longer. There was hot water for the early birds. We did what we could with the rooms, but it would take a forensic cleaning crew to get all the stains out. Little colonies of mould spread across the walls; damp with the remnants of other people’s bad decisions.

We didn’t ask questions. We even got some well-to-dos coming in occasionally. Engaged in things they shouldn’t be. Or simply not wanting to be found. Of course, we couldn’t stop the cops from poking their noses in. They like dead places. In fact, I’d say they’re attracted to them, like bears during the salmon run, just dipping their claws in and seeing who they can drag out, kicking and screaming.

I had an assistant manager. Monk. That’s what I called him, for the greasy line of hair that ran around his ears. He was young to be so bald on top. And his brown hoodie. He always wore the same one.

No one else liked Monk. He wasn’t meant to be liked. He could get cash out of empty wallets. That’s what he was there for. He was body odour and rancid breath, but there was something fierce about him, like a mangy wild animal. He put people on edge. I couldn’t have got by without him. Monk kept us safe. When she first showed up, the inspector, I forgot there were some people he couldn’t take care of.

I am being watched, in the forest. A crunch of leaves gives him away. All the hairs on my body bristle. I can’t tell exactly how close he is, but he’s there, hidden in the decay, weighing me up, like she did, attempting to calculate the potential strength of my resistance. I change course, praying it will be enough to avoid a confrontation.

She marched into my office as I was stubbing out a cigarette, trying to push the grey cloud outside. She handed me the paperwork. I didn’t read it. Her mouth was already open. It was a clean kill.

“We’re shutting you down. Your building’s a fire hazard.”

They go after the lame ones, don’t they? Predators. The ones that are old or sick and don’t have the energy to run away. Despite my best efforts to avoid him, he is closer now. I spot his great haunches rising, his long nose searching out my smell. And then he waits. To see what I will do.

I want to un-see it, the blood stains on the tree stump, the messy remains of a hunter’s kill, because I understand then, too late, that I turned the wrong way. The murder, the terror of it, slips into the pit of my stomach. He’s protecting the grave of another grizzly.

They knocked it down, my motel. I couldn’t watch. I drove by it a couple of weeks later, and it was nothing more than a hollowed-out lot on a forgotten-about street. An ugly scar.

He comes closer, paws the size of dinner plates. I won’t look at his eyes, or his jaw. I don’t want to guess at what he’s thinking. I take my bag off, very slowly. I offer the morels. They’re all I have.

“You’ll like these,” I say quietly. “They’re worth something.”

I lay the bag down in front of me and I back up slowly. His nose twitches. Was it wrong, what she did? I don’t know. Everybody has to eat.

Congratulations to Jo Boxwell, who placed first with Life in Dead Places at this year’s NorthWords Creative Writers’ Fiction Contest, a non-profit partnership between Northwest Community College, Terrace Public Library and Misty River Books.