Photo Credit: Facundo Gastiazoro

Lost in the boreal: in search of BC’s northeast corner

I cross the border into the Northwest Territories leaving the paved road behind in BC, obscured by a tumbling cloud of gravel dust. I squint into the haze as I hurtle down the Liard “Highway” at a hundred. The road narrows to cross a bridge and emerging from the dust are two indistinct shapes. I slow down slightly—watching for bison—and the shapes slowly coalesce into recognizable forms: an old man leaning against the bridge rail, peering into swampy boreal forest; on the back of a battered quad sits his wife, a tiny, deeply wrinkled lady of advanced years. She could be 100 years old or 50—here, years etch themselves into your face like decades.

Neither raises a hand in greeting nor even acknowledges me as I skitter by, kicking up gravel. They disappear into the dust in my rear-view mirror and I wonder if they were really there or just some kind of spirit greeting to a strange landscape. And if they were spirits, what omen did they have for me?

When, several hundred kilometres later, I roll into Fort Simpson (pop. 1,200) at the confluence of the Mackenzie and Liard rivers, with sagging eyelids and a flat tire, I guess the spectre must have been a warning of some kind. At midnight, the smoke from nearby forest fires has turned the usually understated northern sunset into a display of intense colour.

Into the unknown

When I first proposed a book about BC’s four corners, I had only a vague idea what I was up against. The northwest gripped me most: Next to Kluane Park in the Yukon and dwarfed by Wrangell-St. Elias Park in Alaska, Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park is mostly alpine, protected in the 1990s for its namesake rivers. Together with its neighbouring national parks, the “Tat” is part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the largest protected area in the world. Finding information was simple: books, photos, trails and guided raft trips. In 2010, I spent over a week exploring the park’s natural and cultural history.

BC’s northeast is a different beast. It’s a landscape pockmarked by little lakes, innumerable creeks and rivers, and massive tracts of muskeg. The boreal region covers about 60 percent of Canada; it’s the only continuous eco-region spanning the entire globe. When you consider its scale, you realize just how small we are.

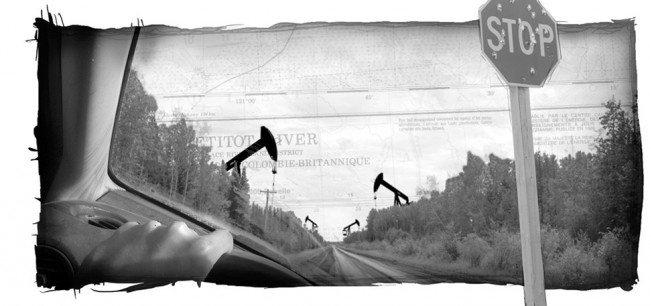

The exploitation of this gargantuan landscape is equally staggering. Northeast BC is etched with the ruler-straight lines of oil and gas development; seismic lines and winter roads traverse thousands of kilometres, crisscrossing the lightly undulating terrain like a giant game of pick-up-sticks.

Accessing the area is a challenge. If you have deep pockets, you can get to the corner by air, not that anyone really goes there. I call up the BC Parks contact for Thinahtea Protected Area and he tells me that in 20 years of working for Parks, he’s never had to issue a visitor permit. The closest recreational areas are hundreds of kilometres away and used mainly by sport fishers paying thousands of dollars to get away from it all. I can’t afford to hire a helicopter.

I worked out a plan to get as close as I could by travelling roughly in a circle around the corner through BC, the Northwest Territories, and northern Alberta. I left in my little Subaru Impreza armed with maps, a large jerry can, a vague idea of what I’m doing and no idea of what I’ll find when I get there.

The caribou conundrum

After a sleepless night in the company of bugs and bears, I leave Fort Nelson, BC and head out into the oilfields, bearing roughly northeast. The wide, well-travelled gravel road is heavily rutted from massive trucks, oil tankers and growling diesel pickups. Feeling dwarfed, conspicuous and vulnerable, I turn up my stereo, grin and wave to construction crews and oncoming traffic.

For 200 km, I grip the wheel as I skid around in the dusty wake of big trucks. This is the traditional territory of the Dene Tha’ and Fort Nelson First Nations, but the only indication I can find is on a map—an ancient village site on the shore of Kotcho Lake. Every now and then, I pass a clearing, marking one camp after another. In the otherwise monotonous landscape are regular seismic paths, unwavering lines cut into the bush that stretch as far as the eye can see.

Development’s impact on the landscape is jaw -dropping. In a research project commissioned by the David Suzuki Foundation, Peter Lee, ecologist and executive director of Global Forest Watch Canada, reported that “there are 16,267 oil and gas wells, 28,587 kilometres of pipeline, 45,293 kilometres of roads, and 116,725 kilometres of seismic lines packed into the Peace Region. If laid end to end, the roads, pipelines and seismic lines would wrap around the planet an astonishing four-and-a-half times.”

Studies on declining caribou populations show that the linear nature of seismic lines is likely affecting how caribou travel and, in turn, how predators hunt the iconic ungulates. Caribou tend to avoid linear features.

Wolves, on the other hand, have no qualms about travelling the easiest path, whether natural or constructed by humans, letting them easily track migratory herds. The rate of development is so extreme that by the time science catches up, it will probably be too late.

After a few white-knuckled hours, I pull off just northeast of Helmet Camp, when the road narrows and signs warn me to use a radio I don’t have. A small oil well monotonously pumps its product from the ground. I glance at my car guiltily. The occasional truck thunders past and I wave with one hand, swatting away a cloud of bugs with the other. There’s not much to see so I spend a few minutes trying to understand what it is I’m doing out here, then climb back in the car and head south again.

The aftermath

After regrouping back in Fort Nelson, I head toward the Territories, planning to circle the corner from the north and approach again from the Alberta side. That’s when my car’s flat tire changes my trajectory. I’m a full three days in Fort Simpson, on the banks of the Mackenzie River.

Forced into inactivity, I walk, read, write, listen to Dene programs on CBC, and think. Despite everything I know about the oilfields and the industry’s short-sightedness, what sticks with me most isn’t the absence of nature, it’s how much nature is still there. I may have felt like I was in rush hour in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by the wheels and cogs of big business and intense industry, but at the same time I was encircled by an enormous natural world, one that I’d never seen before. And the lasting impact of that? I like that world.

Which raises another question: what happens next, when you fall in love with a landscape whose future is uncertain? Worse yet, when that landscape is so big and so far away, how do you hold onto that memory, keep it safe? The northeast corner of BC is in no one’s backyard—it’s so far from any populated centre that it’s easily forgotten, ignored, unknown. But it is there and it is beautiful… for now.