Photo Credit: Photo Emily Bulmer

On track with the right wax

Out on the ski trails, a properly chosen and correctly applied wax can make the difference between tranquility and torment. Though waxing can become highly technical, the recreational skier can produce very good results with a few tools and a moderate number of waxes.

The variables to understand when choosing a wax are temperature, humidity and freshness of the snow, and the relative hardness of the different waxes available. Grip and glide waxes work together to counterbalance the grabbiness of the snow and the amount of moisture that is present. Swix brand wax is rated by air temperature and Toko brand is rated by snow temperature; both are colour coded for easy reference.

Snow conditions

Fresh snow in cold and dry conditions has an intact crystal structure. These crystals are sharp, with many edges, making the texture of the snow abrasive and grabby, like of a piece of Velcro. When the snow is crystalline, a smoother, harder surface on the base of the ski is needed, which can be created using hard glide and grip waxes.

On older snow or in warm and humid conditions, snow crystals break down and become rounder, less sharp and less abrasive—more like the texture of a wool sweater (stuff still sticks to it, but not as much as Velcro). Softer glide and grip waxes are used in this case.

Late spring skiing conditions can create snow textures that are more like silk, as the snow crystals are completely degraded. These conditions require very soft waxes and klister to help draw excess water away from the skis.

Bulkley Valley Cross Country Ski Club head coach Chris Werrell has been waxing his skis since he was seven years old. “I have been around waxing and racing long enough to have a good feel for what we are going to use for the day by the time I have walked from the car to the waxing area.”

His advice to recreational skiers: “Keep it simple! Pick one line of waxes and get to know it well. From there you can branch out to waxes recommended by others.” Werrell emphasizes, “Having the right equipment makes a big difference; a good waxing iron, a waxing jig, a base and groove scraper and sharpener, and a copper-nylon brush will get you through glide waxing. A cork, grip wax, putty knife and wax solvent will work for grip wax.”

Glide on!

Travel over snow on skis also requires glide, which is in part dependent on how much moisture is in the snow. For a ski to glide well, a thin film of water—created by the pressure of the ski on the snow—needs to be present and acts as a lubricant. Not enough water is called dry drag, or friction; too much water is wet drag, or suction. Both slow the skis down; selecting the right glide wax helps reduce these forces. Harder glide waxes create more water film for cold, dry conditions and softer ones create less film, good in warm and humid conditions.

When there is a lot of water in the snow, small groves can be pressed into the finished glide wax with a rilling tool. This helps collect and move water away from the base of the ski. Hydrophobic additives such as fluorocarbons can also be applied to the skis for extra glide in humid conditions. These waxes are toxic (and expensive!) and require the use of a respirator.

Glide wax is applied to the tips and tails of both waxable skis and waxless fish-scale skis for cross-country classic technique, and to the whole ski for skating technique. Glide waxes are also used on downhill and telemark skis and snowboards.

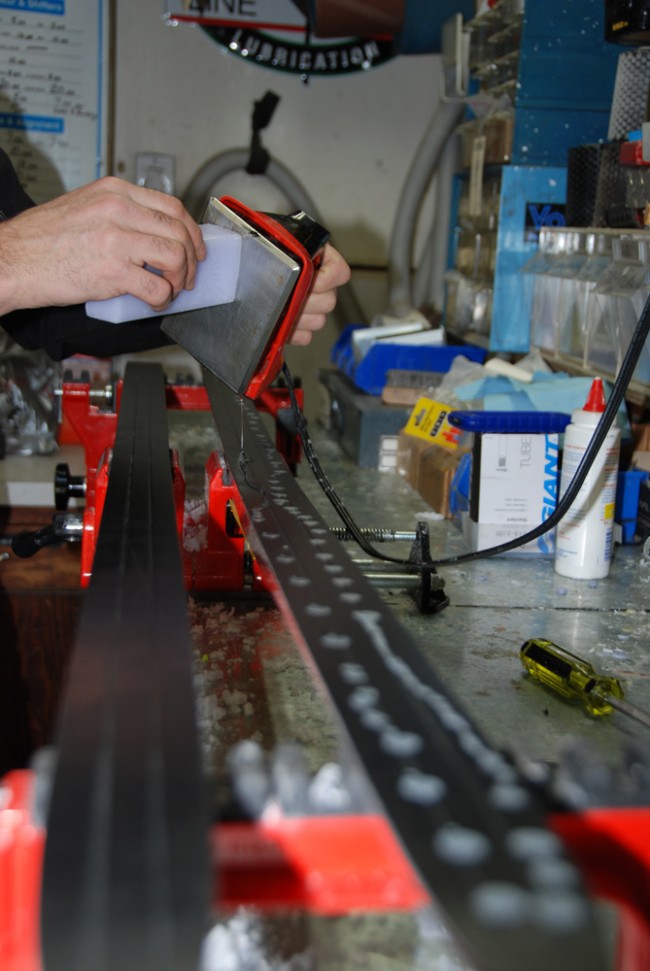

Peter Krause, owner of McBike and Sport in Smithers, demonstrates how to apply glide wax to a pair of skate skis. “The biggest mistake people make is running the waxing iron too hot. Running a hot iron changes the properties of the wax, causes toxic smoke and fumes, and can damage the base of the ski.” He recommends allowing the skis to warm up to room temperature, which will reduce the temptation to turn up the temperature of the iron.

Krause first brushes the skis tip-to-tail with a stainless-steel brush, cleaning out the pores of the base, followed by a couple passes with a nylon brush. He sets the iron and drips wax up and down the ski, then irons over the length of the ski twice. He recommends quick tip-to-tail passes with the iron rather than back-and-forth scrubbing motions, which create hot spots that can damage the base. He lets the wax cool for a few minutes, then scrapes it off with a sharp plastic scraper, scraping out the groves first. “You want a sharp scraper for a clean finish,” Krause says as he sharpens his scraper on a piece of 150-grit sandpaper on top of the workbench. Lastly, he brushes excess surface wax off with a nylon brush, leaving the skis with a glossy finish.

Getting a grip

For classic technique on cross-country skis, grip wax is needed on the centre portion of the ski—the kick zone—to help the skier maintain forward momentum. When the ski is weighted, the camber (or curve) of the ski is flattened and the kick zone contacts the snow. In this moment, you want the ski to stick so you can push forward, then release when it’s lifted. The kick zone depends on the flex of the ski and weight of the skier, but generally extends from about 30 cm in front of the skier’s toe to the heel of the ski boot.

For grip waxing, Werrell recommends that you should have your kick zone marked properly. “The ski shop your equipment came from should help provide this service for you. Apply thin layers—it is easier to cork, and easier to add more layers than to scrape them off. Use the cork vigorously to heat the wax up and smooth it out. The smoother your wax is, the better it will work.” Having two corks, one for warmer waxes and one for colder waxes, makes application easier.

Don’t kiss the klister

When there is no crystal structure left in the snow, the snow behaves like silk, and a sticky substance called klister is needed. Klister is gooey, behaving more like glue than wax, and takes practice to apply. To deal with klister-sticky hands, Werrell recommends putting them directly into your ski gloves. “The sweat on your hands breaks down the klister and your hands won’t be sticky by the time your ski is over.”

Werrell stresses to always ask for help if you are unsure about something. “Skiers are friendly and love to offer advice,” he says. “Local ski shops are great resources too—most owners are skiers as well.”

Coach Werrell’s wax picks for difficult conditions

REALLY cold

Swix LF4 for glide. (Nothing beats it in the cold!) Almost anything for grip—most waxes will work when it gets really cold, but my “old faithful” grip is Swix Blue Extra

Mushy, slushy and warm

Swix HF8/HF10 with a pure fluorocarbon on top, and with a structure pressed into the ski. Depending on how warm and slushy it is, klister will most likely be in the running, or a warm, goopy hardwax like Swix VR70.

Icy

Icy means abrasive! Swix LF4 or LF6 tend to be very durable. For kick, you want a base binder (a harder wax that helps keep the kick-wax on longer)—usually a green hard wax or a cold klister.