Photo Credit: Tavish Campbell

The certainties of LNG development (Commentary/Op Ed)

While it is true that wrapping our minds around the implications of liquefied natural gas (LNG) is anything but straightforward, there are some certainties worth considering.

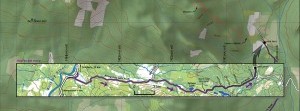

The Skeena watershed is one of the most important wild salmon and steelhead systems on Earth. Wild salmon sustain us.

The Skeena estuary is of enormous biological importance because it provides a diversity of food sources and habitats that support large populations of fish and wildlife in a concentrated area, and it plays a critical role in carbon sequestration.

Flora Bank, located between Lelu and Kitson islands, is one of the largest eelgrass meadows in BC, supporting up to 60 percent of the total Skeena estuarine eelgrass.

Eelgrass meadows are foundational for estuarine food webs via primary productivity, the micro- and macro-invertebrate fauna that they support, and as shelter for extensive juvenile salmon populations.

All Skeena salmon use the estuary as a nursery.

The BC government wishes to use the Skeena estuary as a nursery to grow money.

We humans cannot eat money, but we do harvest food from the estuary: fish, seaweed, clam, crab and too many others to list.

More than pipes: proposed development for the estuary

A tsunami of industrial development is planned for the Skeena estuary, including a bulk-potash loading facility, an expanded rail, road and utility corridor, and two LNG terminals.

The most established of the LNG terminal proposals is for the development of Lelu Island and adjacent waterways. If built, nearly all the ancient habitat on Lelu Island will be destroyed and a marine terminal with a 2.7 km-long elevated causeway to berthing docks will be positioned on the edge of the rich eelgrass meadows of Flora Bank.

A DFO study performed over 40 years ago, when the last wave of pressure for industrial development of the Skeena estuary and Lelu Island occurred, reported that, “Flora Bank is the most important shallow water area of the Skeena River estuary in terms of rearing juvenile fishes. The proposed port development would completely destroy the complex Flora Bank ecosystem.”

Digging deeper

To enable ships to access a materials-off-loading site during construction and the marine terminal during operation, the project plans to dredge 7.7 million cubic metres of ocean bottom―the largest dredging project in Canadian history.

Unfortunately, the now-defunct Skeena Cellulose pulp mill once dumped its toxic effluent directly into the area where dredging is proposed. Sediments contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDD) and polychlorinated dibenzo-furans (PCDF)―all of which are listed as contaminants of potential concern in the proposed project’s environmental assessment application.

Beyond being difficult to enunciate, these are nasty chemicals that will persist and harm life for a very long time.

Movement of the sediment by dredging will uncover and re-distribute these contaminated sediments and will likely increase toxin concentrations near the sediment surface and onto sensitive habitats like Flora Bank.

Many dioxins and furans are bio-accumulative and will bio-concentrate and bio-magnify in the food web. The bio-availability of PAHs, PCDDs and PCDFs will increase with the dredging, and there is high potential for marine life to be negatively affected.

From the smallest micro-organisms to benthic invertebrates, fish and mammals, effects of PAHs, PCDDs and PCDFs may include changes in biochemistry and behaviour, reduced development and reproduction, endocrine disruption, and impaired immune function.

We humans are not immune. We may consume contaminated marine life in which bio-concentration and/or bio-magnification of dioxins and furans have occurred. Effects from such exposure may include biochemical alterations, developmental toxicity, endocrine disruption and cancer.

Prosperity for British Columbians

The LNG industry in BC is proposed to lower global greenhouse gas production, pay off our provincial debt and create 100,000 jobs for BC families; so we are told.

In its report Liquid Natural Gas: A Strategy for BC’s Newest Industry, the BC government states, "BC exports of LNG will significantly lower global greenhouse gas production by replacing coal-fired power plants and oil-based transportation fuels with a much cleaner alternative."

While natural gas emits less carbon dioxide per unit electric power than coal, higher methane emissions cause natural gas to increase global warming relative to coal, particularly on the 20-year time scale. This timeframe is important because Arctic sea ice is predicted to disappear in 20 to 30 years unless global warming is abated. A reduction in sea ice is predicted to accelerate global warming through positive feedback mechanisms: as the area of sea ice declines, the warmer the climate becomes.

When used as a transportation fuel, the methane-plus-carbon-dioxide footprint of natural gas is greater than for oil, because the efficiency of natural gas is less than that of oil as a transportation fuel. Not to mention that the production and transportation of LNG is one of the most energy-intensive industrial processes known. Thus, natural gas is not the “low” greenhouse-gas alternative for the next generation, as promised.

How about paying off that debt? Surely we will milk the financial LNG cow until we are all full on cream.

Economist Marc Lee of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives wrote about the government’s overly optimistic revenue expectations from LNG. Instead of $100 billion estimated from five LNG projects over 30 years, the number is closer to $30 billion (if BC acquired a high-end price for our gas) and more likely $10 billion―far short of the $65 billion debt that LNG is supposed to pay off.

And what of the 100,000 full-time jobs to be created by the industry for BC families?

David Broadland in a recent article for Focus Magazine wrote that, “a $98 billion project in BC would create 910 long-term operational jobs at LNG plants, 56 pipeline jobs and 1,456 gas field extraction jobs. If the pertinent BC Stats Input/Output Model multipliers are applied to these long-term employment figures, the total number of long-term jobs―direct, indirect and induced―rises to 21,000.”

Reality check

OK, I have a tainted view of the world; I admit it. My thoughts primarily concentrate on fish. Well, that’s not entirely true. I think often of our children, and the generation to follow. I think of the strong dependence that living beings of our watershed have on fish. I think of how important salmon are to our future.

I’m concerned about the continued erosion of their home, their nest and nursery―that death-by-a-thousand-cuts reality, which has served to reduce the numbers of salmon returning to the Skeena and beyond. Chum, only a century ago numbered in the hundreds of thousands, now appears to be in the thousands. Sockeye, once the reason for pioneer settlement in Port Essington and other cannery towns along the Skeena River and estuary, are now propped-up by artificial spawning channels. The rush for financial gain has bestowed such a legacy.

Here we go again.

We have known for more than 40 years that near-shore areas of the Skeena estuary, like Flora Bank, sustain much more than marine life; they sustain us. Why would we now zone such an ecologically and culturally important area for industrial development?

Building LNG projects atop the most productive salmon habitat in the Skeena does not fit my vision of a sustainable future. We can do so much better.

Michael Price is a salmon ecologist with SkeenaWild Conservation Trust; he lives in Smithers. pricem@skeenawild.org