Photo Credit: Facundo Gastiazoro

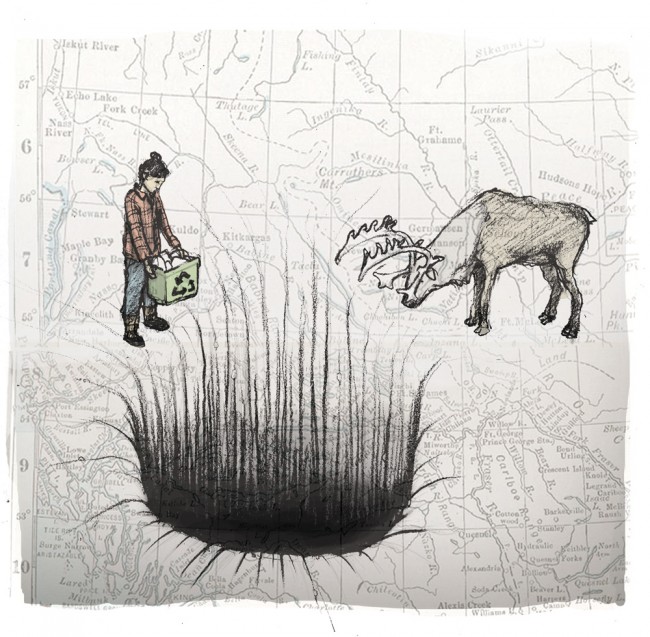

Northern recycling: How new programs are leveling the field

Like many who move to the North, I wanted to live closer to the land. I wanted to compost, eat locally and do all those things that feel like living gentler. And, like others, I was surprised to learn how limited recycling was in my community.

For the first couple years, I stockpiled my plastics and took them on trips back to my previous home in Alberta. As those visits tapered off, I began buying less, avoiding clamshell packaging and checking plastics for the #2 that indicated they could be recycled.

But I confess—more than a few clamshells have made it into my trash bag. Those grape tomatoes are just too darn tempting.

A little investigation into northern recycling doesn’t shed a lot of light: Communities like Smithers and Prince George collect only #2 plastics while Vanderhoof, Quesnel and the Peace collect the whole gamut. Some offer curbside pick, but many don’t. And where does that tin and glass taken to the dump end up?

As it turns out, I’m not the only one questioning our northern recycling facilities. Telkwa recently implemented a curbside recycling program, and Smithers and Terrace are preparing to do the same through the Multi-Materials BC (MMBC) program. A new approach to recycling is making it more accessible and more uniform.

Traditionally, governments were responsible for recycling. Recent legislation shifted that responsibility to producers: the companies that create the waste now have to pay for its recycling. This shift is creating changes for the North.

The downside to distance

According to Craig Wisehart with Electronic Products Recycling Association (EPRA), an agency with Stewardship Agencies of British Columbia, this new approach to recycling transferred the cost onto the consumer, with visible environmental handling fees (EHF) and, occasionally, hidden costs. (For example, on top of the deposit you paid on that drink container, there is a built-in cost for recycling.)

“Panasonic couldn’t practically go out into the market and collect all those materials,” he says about large corporations whose products often end up in the landfill. What they can do is fund recycling programs.

Producers then pass the recycling legwork onto stewardship agencies, such as the 16 listed under Stewardship Agencies of BC that cover appliances, lighting, batteries, paints and more. Here’s where things can get confusing: not all those materials are deposited at the same depot. So your defunct light bulbs will likely require a different destination than your cardboard.

EPRA has 166 depots for electronics recycling across BC, including several in the North. Once collected, they are consolidated in six centres, the only northern one being in Prince George. Last year, the agency collected 23,000 metric tons of materials total, with 886,000 kg—roughly three percent—coming from the North.

“For us, when you get into very remote locations where there’s five people and 12 caribou, it isn’t possible for us to have a depot,” Wisehart says.

And therein lies the problem: It’s not that northerners don’t want to recycle, it’s that the costs for transportation are often prohibitive. When you require businesses to clean up after themselves, the cost is built into the product.

For EPRA, the fee charged to consumers to recycle the product is equal to what it costs to recycle all the products across BC, regardless of distance. To some extent, those in more populated areas subsidize recycling in remote areas, like the North.

“The fees we charge within BC are fees to recycle across BC,” Wisehart says. “In our ideal world we are charging exactly what it costs us to recycle.”

Curbing our waste

The current changes in BC are to packaging and printed paper (PPP). In 2011, an amendment to the province’s 2004 Recycling Regulation, which moved responsibility for end-of-life products from government to industry, required PPP stewards to submit a program plan to government.

The result was Multi-Materials BC, a program that’s hit some road bumps in its implementation, but appears ready to change the face of recycling in some northern communities.

With MMBC, a non-profit society, companies are charged according to how much packaging they put into the market. Those fees are then used as incentives to set up local recycling programs. The program, which is only for residential paper and plastic, uses existing infrastructure—such as curbside garbage pickup—but offsets the costs for communities.

“In some areas, particularly in the North, we’ll see new services started,” says MMBC managing director Allen Langdon. Communities signed up for MMBC include Smithers, Terrace and Telkwa.

“For Smithers, we’re finally getting curbside recycling, which is something people have wanted for a long time,” mayor Taylor Bachrach says, adding that the range of materials recycled will increase—particularly when it comes to plastics. “Hopefully this will give northern communities more opportunities when it comes to recycling services.”

Smithers and Terrace are scheduled to start curbside recycling on May 19, with Telkwa’s recently implemented pilot program to shift over to MMBC. But some questions remain: Most importantly, how far will municipalities need to ship materials and at what cost?

Under the contract signed with MMBC, communities get an amount per household and are responsible for passing off the recyclables to a post-collection service, which is within

60 km. MMBC is just beginning to put in place post-collection sites where recyclables go prior to processing.

The farther materials need to be trucked, the less cost effect the system is for communities. In early March, Smithers and Terrace were still waiting to hear where their post-collection sites would be.

Cutting back

Prince George is one municipality that opted out of MMBC. Currently, two local businesses provide curbside pickup for about $10 a month per household.

“From my understanding, it just wasn’t cost effective,” Prince George’s Recycling and Environmental Action Planning Society (REAPS) executive director Terri McClymont says about MMBC. “There’s still a lot of work that needs to be done and there’s still a lot of consultation that needs to be done.”

Although collection and consolidation happen in the North, ultimately the materials need to make their way down south for processing. Ideally, the North would have its own facility, but McClymont says that would take a large incentive in the form of capital startup costs.

“A lot of the communities in the North are struggling to find something for their budget,” she says. “It’s very costly for us to collect and then ship down south.”

On the bright side, maybe as northerners our lack of recycling facilities has built better habits: buying less, reusing more, recycling as little as possible.

Oh, as for the tin and glass those in the Bulkley Valley meticulously take to the waste transfer station: the tin is compacted into old refrigerators and shipped down south for recycling. The glass it processed separately, for safety reasons, but ultimately ends up in the landfill.