Photo Credit: Photo Bruder/Freshwater Fisheries Society of BC

Hope for the Nechako Sturgeon

When fisheries biologist Cory Williamson tickles the water to simulate feeding, a two-metre dinosaur ghosts out of the shadows and glides across the brood-tank floor. Khaleesi (named after the Game of Thrones character to reflect her feisty nature when captured) is a 70-year-old female white sturgeon. Light grey in colour and covered in bony platelets, this pre-historic holdover is a resident of the Nechako River. She is being kept through the winter in the new Nechako White Sturgeon Conservation Centre in Vanderhoof, in anticipation that she will be ready to spawn this spring.

Life is pretty easy for the queen sturgeon. Square meals have led to a nine-kg weight gain since last April and she has another 45-year-old female, Slimey, as a companion. But I can’t help wonder if she realizes that the fate of the entire Nechako population rests on her bony shoulders.

“The International Union for Conservation of Nature describes the 27 species of sturgeon that occur worldwide as the most endangered vertebrates on the planet,” Williamson says. In BC, sturgeon in the Nechako, upper Fraser, upper Columbia and Kootenay rivers are endangered under Canada’s Species At Risk Act (SARA), while sturgeon in Alberta and across the prairies to Ontario and Quebec are also at risk. Nechako white sturgeon were SARA-listed in 2006.

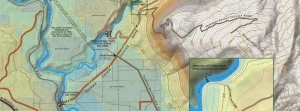

The largest North American freshwater fish, white sturgeon have been around some 200 million years. Historical estimates suggest there were once 5,000 to 8,000 sturgeon living within the Nechako River watershed, including Stuart Lake. That number has plummeted below 500. Scientists believe that Nechako sturgeon have not successfully spawned and reared in the wild in over 40 years. Indeed, Slimey may be one of the youngest naturally spawned sturgeon living in the river today.

If Khaleesi could talk, she would tell you the tale. The Kenney Dam was built in the early 1950s to power what is now Rio Tinto Alcan in Kitimat. The dam blocks the Nechako River’s natural headwaters, once considered the Fraser River’s second largest tributary. Most water in the dam’s 900-square-km reservoir runs west, tumbling through a 16-km tunnel in the Coast Mountains to turn the generators at Kemano, 800 m below. Some 75 km west of the dam, excess water is released over the Skins Lake Spillway into the Cheslatta River, which joins the Nechako eight km from the dam. But the Nechako flows have never been the same—and that’s the problem.

Working to save sturgeon

SARA documents clearly state that lack of water has led to the sturgeon’s demise. The river is prone to silting and greatly reduced spring water flows do not clean out spawning and rearing habitat, nor is there a flooded nursery area for the tender young fish.

Khaleesi’s new hatchery home is part of the Nechako White Sturgeon Conservation Centre, which opened in Vanderhoof last June. The Sturgeon Recovery Initiative based in the centre has a mandate “to return the sturgeon to a self-sustaining population.” That means replacing lost stocks that are not building naturally, as well as restoring and building spawning, rearing and wintering habitat and engaging the public to be stewards of this fragile species. Ongoing sturgeon research is also part of the job. The centre is operated by the Fresh Water Fisheries Society of BC, with Williamson as the manager.

“The hatchery facility is only a stop-gap,” Williamson says. “If the sturgeon don’t spawn naturally, it is only going to go so far. But as soon as we started putting fish in the river, that’s a big success.”

Sturgeon are late bloomers, which doesn’t make the recovery initiative’s job easy. Males mature after 20 years, while females may take up to 40 and only spawn every three to 10 years. When they do, they make up for it with 3 to 4 million eggs from the largest adults.

Spawned sturgeon eggs are naturally sticky, helping them stay put in the crevices between river gravel while they incubate. Eggs hatch in about 15 days and are at a larvae stage for another two weeks. In just over a month, they are juvenile sturgeon, complete with long snout. Juveniles eat insects, freshwater clams and snails, while older adults eat fish, particularly salmon. In the Nechako, a fully-grown adult can be up to three metres long, weigh 125 kg, and live for over 100 years.

Silty setbacks

A trait that puts sturgeon at risk worldwide is their habit of spawning in only one location: “That is consistent with what we see in other populations,” Williamson says, “which is their downfall. If you change a river, you change a specific location and they don’t have the ability to adapt. They are not colonizers like salmon.” In the Nechako, that spot is just up from the Vanderhoof bridge.

“As a result of flow management and land practices, their spawning habitat has been impacted,” Williamson says. “So the other big job is to figure out how to fix the problem and get them spawning on their own in the long term.”

Back in 2007, Mother Nature showed that she still had the chops, with a flood on the Nechako that cleaned out the spawning beds and provided more water suitable for early rearing. “Lo and behold we got some natural spawning,” Williamson says. “It wasn’t much, but it’s the first since some 15 years after the dam was built.”

In 2011, the recovery team placed clean gravel on the spawning beds and deposited fertile eggs that successfully hatched. “We also have fish swimming around from 2011,” Williamson says. But many areas of the new gravel have filled with silt.

“We think we know the biology of what is going on there now,” Williamson comments. “It is a matter of understanding the physics of how the river moves its sediment.” He says he has spent a lot of time working with hydrologists. “The next move is to take that info to some engineers and say, ‘This is what we want, how do we build it?’”

Will it work?

A Quebec project makes Williamson optimistic: a spawning platform designed for sturgeon impacted by the James Bay hydro project in northern Quebec.

“They kept the same real estate—the square footage and the location—but they have engineered some structures that are pretty amazing and they work,” he says. “Our task now is to design something that is both cost effective and does the job.”

He credits community support, noting volunteers were involved with early hatchery experiments run out of a C-can from 2006 to 2009. The District of Vanderhoof donated land for the conservation centre and the town raised $300,000 to help with construction. Operating funds have been established to sustain the hatchery program for 10 years with support from Rio Tinto. Local First Nations have also been involved.

During the 2014 spawning period, the conservation centre had 72 different sets of eggs hatching in rapid succession and needed extra hands. Each batch had to be stirred with a feather for an hour to mix in industrial clay to remove their stickiness so the eggs would hatch evenly. Sixty volunteers showed up through the week to help out: “When you have a dozen people standing around a trough stirring eggs, there are lots of cool conversations about sturgeon and about what they see in the river,” Williamson says.

In May, area schools joined centre staff to release 700 hatchery-raised juveniles tagged with transponders that will allow students to track the fish. Sturgeon located by researchers have their tags scanned and recorded on the Where’s My Fish link on the conservation centre website. Students can log in and see if their fish has been spotted in the river.

It may just be the start of engaging the next generation in saving this prehistoric species.